Caring for Creation: a Christian Calling

The Christian Roots of Environmentalism Part 1 | Guest post by David F. Garner

The Cover of The Compleat Angler by Izaak Walton | Amazon.com

Where did the concept of environmentalism originate? Was it the natural result of a mass exodus from Christianity or did it arise from a pagan worldview? Many excellent books and articles provide in-depth research on this topic. Here we will survey all those mountains of pages from a high overlook. The environmental movement has had Christian influencers from the beginning. Names include Charles Spurgeon, Theodore Roosevelt, and C. S. Lewis.

A Centuries-Old Movement

Many assume environmentalism sprang up in the 1970s from the fertile soil of secularism tilled by the hippie movement of the 1960s. Historians refer to the 1970s environmental revolution as a second-wave conservation movement. This modern approach is a reinvigoration of a movement dating back to the mid-1800s. Laws governing the use of natural resources are nothing new. Nearly every major civilization in history has debated and regulated the use of natural resources to combat over-consumption to some extent, including ancient Israel. The modern Conservation Movement differs from many ancient efforts because it emphasizes nature’s intrinsic value. A keen respect for the creation has not always existed in Christian theology.

Most major Western Christian traditions, such as Catholicism and Anglicanism, have historically subscribed to Thomas Aquinas’ view of nature which assigned it a low status. According to Aquinas, animals and nature, in general, belong to man to do with as he pleases. There are no moral guidelines for their treatment. The concept of animal or environmental welfare was virtually non-existent to Christians in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period. Aquinianism was dominant and went virtually unchallenged until 1776 when Humphrey Primatt published Dissertation on the Duty of Mercy and the Sin of Cruelty to Brute Animals. The 19th century saw a significant shift in thought in Western society with the rise of concepts like animal rights and humane treatment. This shift in thought precipitated the Conservation Movement. Many Christians were at the forefront of fighting for this change.

Two books published in England during the 17th century were landmark in their presentation of conservation management ideas and laid the groundwork for modern environmental conservation thought in Western culture.

In 1653 Izaak Walton published The Complete Angler, part how-to fishing guide, part conservation guide for protecting waterways and fish populations. Reprinting continues to this day. Walton sought to remind his readers of the importance of water. "The water is the eldest daughter of the creation, the element upon which the Spirit of God did first move, the element which God commanded to bring forth living creatures abundantly; and without which, those that inhabit the land, even all creatures that have breath in their nostrils, must suddenly return to [death]." He laid the groundwork for modern conservation law and one of the oldest water conservation organizations in the United States is named in his honor.

In 1662 John Evelyn published Sylva, one of the most highly influential works on forest management. He stressed the importance of conserving forests by replanting trees to replace those cut down. He based his case on the Genesis model. "As paradise (though of God's own Planting) had not been Paradise longer then the Man was put into it, Gen 2:15, to dress it and to keep it; so nor will our Gardens (as near as we can contrive them to the resemblance of that blessed Abode) remain long in their perfection, unless they are also continually cultivated."

These two men helped to bring the idea of nature conservation to the attention of the Christian world. They were men ahead of their time. It was not until the middle of the 19th century that conservation became a widespread concern.

In 1822, Irishman and Protestant Richard Martin authored an act of the English Parliament preventing cruelty toward cattle. It was the first animal rights legislation in the English-speaking world. This was not Martin’s only effort on this front. He had previously voted for two other failed bills that would have restricted animal fighting. He was bestowed the nickname “Humanity Dick” by King George IV. He was also a founding member of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals established in 1824. This society is considered the first animal rights charity and was primarily founded by Rev. Arthur Broome along with several others including famed abolitionist and hymn-writer William Wilberforce.

Martin, Broome, and Wilberforce were all doubtless influenced by Primatt’s dissertation. Broome is known to have republished and distributed copies. These men were only a handful of the animal rights activists in the first half of the 19th century who succeeded in changing Western society’s view on the treatment of animals.

Conservation Becomes a Movement

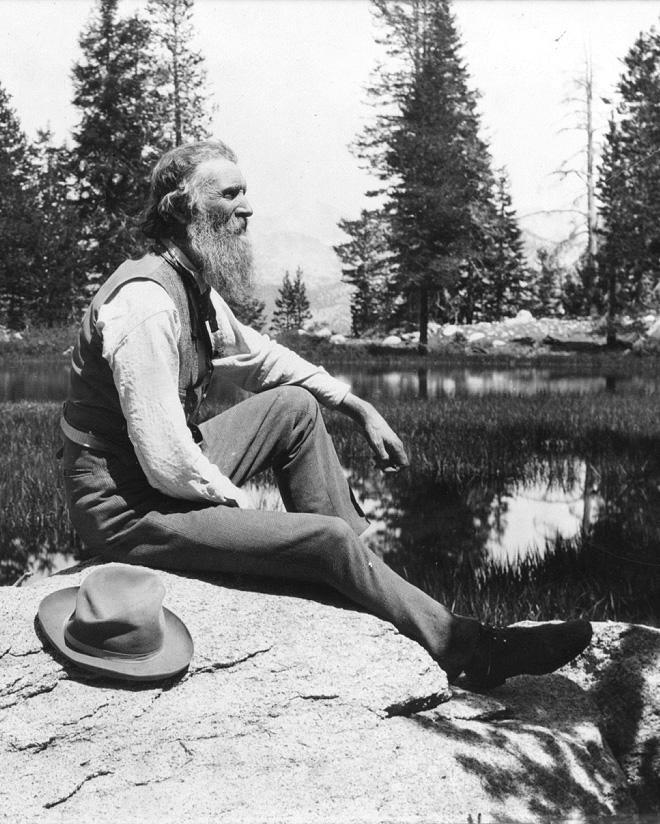

John Muir by unattributed - US Library of Congress, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40843989

Many great thinkers have contributed to the discussion of managing natural resources, but one person is widely considered the originator of the modern Conservation Movement in the West. George Perkins Marsh and his influential 1864 work, Man and Nature, defined the problem of environmental degradation due to the overuse of the earth's resources. He also laid out solutions to help correct this. He was one of the early heads of the U.S. Forest Service and contributed much to the science of forest management.

Where did he get his ideas about preserving nature? He first noticed the negative impact human activity could have on nature in childhood when he observed that clear-cut logging reduced the amount of rain the soil could absorb, thus increasing flooding. His father was a Calvinist and an amateur naturalist. He continued in the faith of his parents throughout his life. Biblical thought permeated his ideas about nature and undergirded his conservation notions as they mirror biblical stewardship.

Following the publication of Marsh's book, political and cultural efforts slowly arose to combat the pollution and destruction wrought by the Industrial Revolution and urban development. These efforts were not unique to the United States. A realization of the need for better management of natural resources rose in many industrialized countries. The U.S. became a marquee location for conservation policies and influenced the global current.

John Muir, the legendary environmental writer of the late 1800s, is another early example. His writings, speeches, and political actions helped to establish the U.S. National Parks system and establish a worldwide conservation movement. He founded the Sierra Club, which is still one of the most prominent environmental organizations. One finds much biblical language and symbolism when reading his books. He compares lovely vistas to the Garden of Eden and talks about God's "water and stone sermons."

His father was a conservative Christian minister of the Presbyterian persuasion. Daniel Muir portrayed a harsh and exacting God to his children. He viewed nature as a commodity solely to serve man's interests. It would be understandable if John had disposed entirely of his father's faith as he most certainly did with his attitude toward nature. Instead, John came to have a reverent passion for nature. He did not forsake his childhood faith in God, although he had little patience for organized religion.

Any reader of John Muir's writings cannot miss the abundant religious language and references to God. The sheer number of remarks to finding God in nature convey a high approbation for the Creator God he found there. Additionally, his faith informed his approach to nature conservation. It was precisely because Muir found a connection to God in nature that he held it in such high esteem. One of the many biographers of John Muir, Cherry Good, makes this point well. "[Muir] preferred to worship outdoors, where he could see God's hand in the beauty of nature, rather than within the four walls of a church." She points out that an acquaintance of John's recalled, "Though ardently devoted to science, as well as the study of nature, yet the agnostic tendencies that had their beginning about that time found no sympathy with him. With him there was no dark chilly reasoning that chance and the survival of the fittest accounted for all things." For Muir then, faith and conservation were not at odds. Instead, they fit together naturally. It is obvious that his respect for nature, where he discerned "divine lessons," was strongly informed by his Christian upbringing.

In England, a similar movement was taking place. Social reformer Octavia Hill, a member of the Anglican church, led change in many areas, including the development of hiking paths. She desired the urban poor to have access to natural open spaces. Her most significant legacy is starting the National Trust in England, which became a model for other countries. It preserves land tracts converting them to parks and natural spaces for the public. One of its most famous parks is the Lake District.

President Theodore Roosevelt grew up in a Presbyterian home and was a devout Protestant throughout his life. He was also an avid naturalist and conservationist. Americans memorialize Roosevelt for establishing the U.S. National Parks Service, although he accomplished much more than this for conservation. He sought not only to protect the environment but also to encourage others to adopt this goal. He said, "Here is your country. Cherish these natural wonders, cherish the natural resources, cherish the history and romance as a sacred heritage, for your children and your children's children."

Roosevelt was the most outspoken conservationist of the presidents in the Progressive Era. In this same era, Presidents Harrison, Cleveland, and Wilson also helped the Federal government make dramatic strides in protection of the environment. All of them came from Presbyterian roots. Environmental conservationists have come from many backgrounds, but Calvinism and Presbyterianism produced more major conservation leaders than any other persuasion in the movement's first century. John Calvin regarded nature as a place to draw near to God and commune with him. To many in the Calvinist tradition, nature study holds an aura of sanctity. Historians, including Robert Nelson and Mark Stoll credit Calvinism as the primary historical taproot of the environmental movement, not any secular or pagan tradition.

Further Christian Roots

Sigurd Olson is yet another giant in the anthology of great conservationists. Like so many others, he was the son of a Christian minister, in this case, Baptist. Throughout his life, he confirmed that the Christian view of creation care inspired his conservation efforts. He maintained a notion of Creator God throughout his life and argued that God's love for all creatures was reason enough to actively seek to preserve them.

"Wilderness to the people of America is a spiritual and cultural necessity, an antidote to the high pressure of modern life, a means of regaining serenity and equilibrium. We go there for perspective and the good of our souls and to recapture our lost sense of oneness with the earth and to know the presence of God." -Sigurd Olson Fisherman's Sunday

David Garner is a freelance writer, author and speaker. He is regional director at F5 Challenge ministry. He resides in Tennessee with his family. For more on creation care and Christian conservation, read Christian History Magazine #119: The Wonder of Creation.