Finding Hope from Oppression

Caesarea Philippi and the Black Church in America | A post by Grace Pointner, CHI Intern

Caesarea Philippi | Image by Grace Pointner

I could get there in my sleep if I had to—the place where Jesus stood with Peter and told him he would be the rock of the church: Caesarea Philippi. The place where I first considered the importance of churches sprung from oppression.

Oppressed peoples make up so much of the world, raising questions about where hope may be found. Will there ever be redemption? Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? How can something good come from injustice? Jesus’ ministry to the marginalized speaks into these questions, but his message in Matthew 16, spoken at Caesarea Philippi, gives even more hope. For when Jesus said, “on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it,” he was speaking of churches built out of hardship— churches built on the brink of hell.

Caesarea Philippi is an ancient city characterized by rich soil, healthy streams and rigid cliff faces spotted with caves. Before acquiring its current name, Caesarea Philippi was known as Panion or Panias because of its ties to the god Pan, a half-man, half-goat god. A major source of the Jordan river spouts from a large cave in this area, a feature that lent itself to the ancient cult worship of Pan, a site also known as Banias. Worshipers of Pan believed that Banias was an entrance to the underworld, thus, the streams were used as places to sacrifice to Pan. Their ways of worshiping, however, were brutal.

Pan, the god of the wild, required much. Nudity, sex, bestiality and sacrifice were all part of what went on at Banias in order to please Pan. The worshiping was so horrible, it had to be done outside the city gates. Sacrifices, both animal and human, were thrown into the bottomless pool inside the cave. Bodies that sank meant Pan was satisfied; the ones that floated required more worship. The stream flowing from the cave was said to run red with blood. Niches for idols were carved in the cliff face to create a temple sanctuary for these wicked acts.

Image by Grace Pointner

Jews were forbidden to step foot in Caesarea Philippi because it was known to be the “gates of hades itself” and a place of oppression and sin. However, the screams, the stench, and the blood were all part of the backdrop when Jesus revealed to his disciplines that He was the Messiah. The rocks of Caesarea Philippi were where Jesus said that his church would be built and that the gates of hades— Banias— would not overcome it.

This is the history that echoes in the air of modern Caesarea Philippi— a history of sin and a history of Jesus’ Gospel mission. The place where heaven meets hell and prevails over it. And I remember being there, softly crying at the sight of the cave, the niches, and the water that was once red. It was there that my pastor gave this message: Jesus chose this place specifically to build his church, because he knew his church would spring from oppression and not be overcome by it. Beside the gates of hades and a cave filled with death, Jesus stood up and told Peter to build the church on this rock— on the rock of Hell itself— for this is where Jesus' Gospel redeems, shines light, and purifies. Where there is oppression, the Gospel gives hope that cannot be overcome.

This interpretation of Matthew 16, spoken to me with geographical and historical context, became the way in which I began to understand the role of churches sprung out of oppression. But I wanted examples. My experience as a white woman living in a small, generally safe neighborhood doesn’t lend itself to firsthand experience with mass oppression. So I asked myself what churches have indeed risen out of oppression? According to Jesus, these are the churches that will not be overcome, these are the churches that I should learn from.

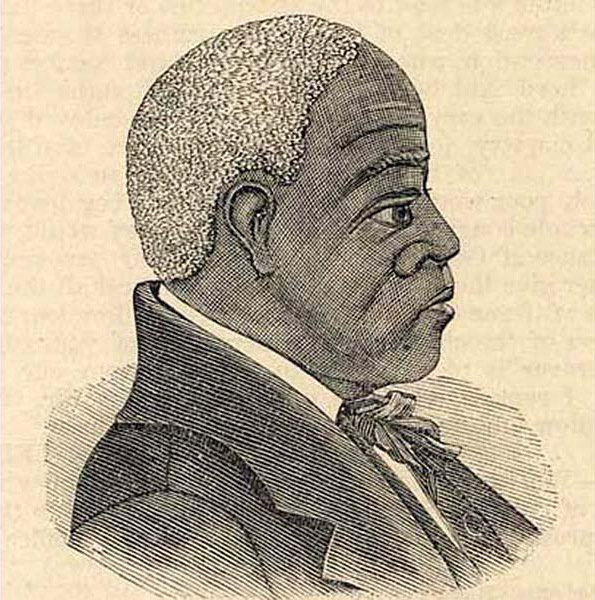

The story of the Black church in America is wrought with oppressive narratives, making its formation a beacon of hope. With the Bible and baptism as its backbone the Black church struggled into existence in Savannah, Georgia around the late 1700’s amidst the horrors of the African slave trade. Only the Methodists and Baptists licensed Black pastors to preach; all other denominations forced slaves to attend White-led churches that preached in support of slavery. It was these very churches that persecuted and harassed the Black church. Through these trials, however, strong leaders arose who pressed forward in their ministry despite the constant threat of imprisonment or beating. One such man, George Liele, evangelized to both free and enslaved men and women amidst the Revolutionary War period. Leaving Savannah after the war, he passed his small congregation of baptized Christians to the young Andrew Bryan, a slave he had baptized not long before. Bryan’s master let him preach and become an ordained minister in 1788, accelerating the growth of the Black church and allowing it to become certified by the George Baptist Association in 1790. In fact, the Black church grew at a significantly higher rate than the White baptist churches, which wouldn’t become certified for another five years. After Bryan bought his and his family's freedom he dedicated his entire life to the church which he pastored until his death in 1812. By 1831 the African Baptist Church, originally composed of only a few baptized slaves from Savannah, George, had 2,795 members and was rapidly growing.

Reverend Andrew Bryan | Wikipedia

Although the North was more open to Black churches, most Black Christians still worshiped in churches led by White pastors. Black Americans could join “groups,” not churches, that represented independent Black Christians. Organizations such as the Free African Society of Philadelphia, founded by Richard Allen and Absalom Jones in 1787, was one of these religious groups that offered hope for a future Black Church. Indeed by 1810, there were 15 Black Churches from South Carolina to Massachusetts that were affiliated with specific denominations familiar to us today: Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian. Indeed, an offshoot of the Free African Society of Philadelphia was Bethel Church, the founding church of the African Methodist Episcopalian (AME) denomination.

During the Second Great Awakening of the early 1800’s Methodist and Baptist missionaries implored slave owners to allow their slaves to go to church and have religious freedom. Pre-abolition laws inhibited these hopes, but ignited a vision for a church led by free Black men and women. The events of the late 1800’s— the underground railroad, the Civil War, emancipation, reconstruction and the migration of freed slaves to the cities— emboldened the Black church to adopt political and social ideologies that fought for liberation and autonomy. Heroes of the Black Church like Frederick Douglass and AME Bishop Daniel Alexander Payne paved the way in educating a new generation of Christians who would stand behind a church led by Black Christians. But one constant throughout the history of the Black Church is this: it was formed while being oppressed, making oppression itself their lens for theology, biblical interpretation, and political affiliations.

“Black Christians simultaneously shared and departed from ways that White evangelicals understood the Bible and faith” writes Jay R. Case in his article in issue #138 of Christian History Magazine. “Like White evangelicals, they believed in the authority of the Bible, the significance of Christ’s atoning sacrifice, the necessity of conversion, and the importance of evangelism. But Black Christians also prioritized a truth from the Bible that White evangelicals did not often emphasize or fully explore: God frees us from more than our sins.” (Case, 24-25).

Bingo! The Black Church, identifying with the Exodus of God’s people in the Old Testament, finds hope in the truth that God saves them from unjust bondage. Furthermore, New Testament revelations in 2 Corinthians remind believers that whenever we are weak, Christ is strong. The oppression experienced by the church leaves room for God’s power, closeness and justice to be revealed. Responding to a society dominated by White slaveholders, the Black Church leaned into the truth that God brings justice to the oppressed with His final judgement, and mercy to the oppressed through the hope of the Gospel provided in the meantime. Indeed, it is not in-spite of oppression that the Black Church finds hope, it is because of it. By grace, through faith, the oppressed are freed and are given hope; this is the word that churches sprung from oppression can preach with certainty.

The Black Church continues to be characterized by liberation theology, the belief that stresses care for the oppressed and reform of unjust structures. This belief reveals itself in the hope Christians receive who are bombarded with stories of suffering or the experience of oppression. The Black Church, a church sprung from slavery, trusted in God’s liberation and justice, building a church community rich in hope. Indeed, on the rock of horrific oppression and injustice, God built a church that has not, and will not, be overcome. And the universal church, as one body in Christ, can join their Black brothers and sisters in professing hope and lamenting injustice, just as Christ invited his disciples to enter into the suffering of the people at Caesarea Philippi. Indeed, even I can find hope and enter into lament.

I can hear my pastor saying, “have hope” as we stood in the waters of Caesarea Philippi, looking at the mouth of a cave once filled with death: “Jesus uses these places of oppression to save his people.” And so Jesus has used the Black Church in America, a church born in slavery, to preach the truth of God’s word which is justice, mercy, trust and faithfulness.

Grace Pointner recently completed her Bachelor of Arts degree in Communications Media with a minor in Anthropology from Wheaton College, including an internship with Christian History Institute. She is pursuing a career in freelance writing and marketing. "Meet the intern" in our staff feature here.