The Making of Martyrs

by Dan Graves, layout editor, Christian History.

I WAS FOURTEEN when I discovered Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563) in my grandparents’ basement. Sitting on a pile of old newspapers with a sump pump kicking in every quarter hour, I devoured the pages. Both repulsed and fascinated, I could not lay it aside.

Before reading Foxe, I had some idea of cruelty. I had barely escaped a kidnapping when I was seven and had lived next door to a girl whose brother pushed her into a fire in a rage. But to deliberately, systematically torment others merely because they were followers of Christ—that was fiendish beyond my comprehension. Millions of Jesus followers around the world live with such consequences today, which helps account for the book’s continued popularity and relevance.

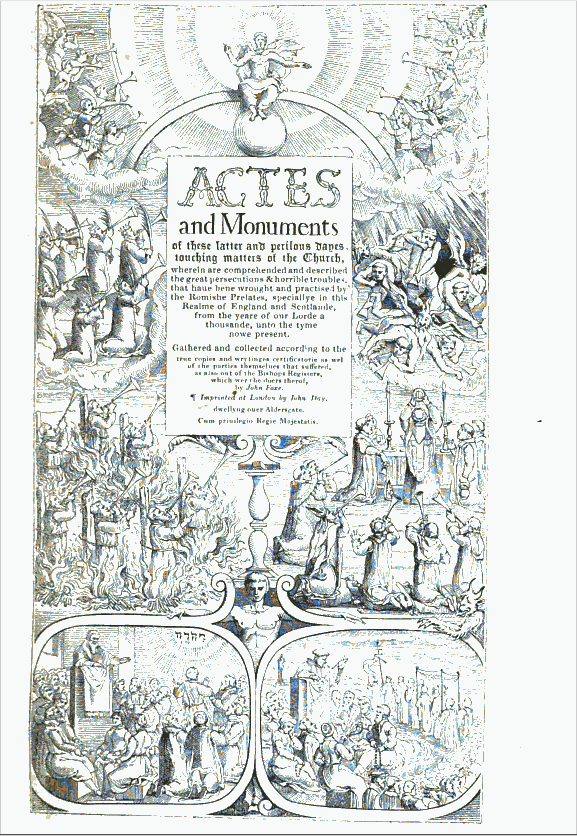

Foxe’s original aim was to show that England was God’s chosen nation and that her sixteenth-century martyrs, executed by Henry VIII and Queen Mary, were part of a great tradition that stretched back to the apostles. His massive book (over 1,800 pages) was titled Actes and Monuments.

Although the book’s politics soon grew dated, its stories of heroic Christians seemed timeless. Editors excerpted them. Countless readers pored over numerous versions. Demand never waned. A search on Amazon turns up dozens of editions of the Book of Martyrs. Some incorporate stories of recent martyrs and some include illustrations.

From the start scholars complained that Foxe handled some material unfairly. He often had to rely on accounts colored by indignation, and he added his own bias. His book spread a vision of Protestant heroism that helped alienate British Protestants from Roman Catholicism. While scholars still recognize the value of Foxe’s sources, it is the narrative he created from those originals that made Foxe a household name.

[NOTE: This is a expanded version of a review that appeared in Christian History issue 116. Read the rest of the reviews at Twenty-five Writings that Changed the Church and the World.]