Ministering until the End: Moon Jun Kyung

A guest post by Ranmi Bae, part II

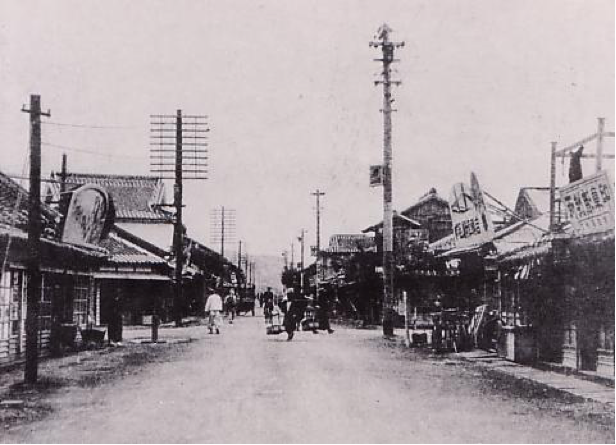

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

See part I on the early life and conversion of Moon Jun Kyung, twentieth-century Korean female martyr.

Moon Jun Kyung’s church in Mokpo actively encouraged women’s and lay ministry, following the holiness tradition. This was clearly shown in the denominational school, Gyeongseong (now Seoul) Bible School, which unusually was co-educational and produced more female than male graduates. Encouraged by this environment, Moon enrolled in the school at the age of forty as an auditing student, since she did not meet two of the admission criteria: being an unmarried woman aged between twenty-five and thirty. Soon, she asked her husband for a divorce to be eligible to receive financial support for tuition and housing as a full-time student. Given that Confucian norms required women to remain subservient to their in-laws, even posthumously, such a request shows that she was gradually distancing herself from the Confucian worldview. As a Confucian nobleman, her husband refused this request. Eventually, in September 1932, a year after her initial enrollment and on the recommendation of a prominent pastor, she became a full-time student.

The school’s curriculum was a bit different from today’s seminaries. Students spent their mornings studying the Bible, afternoons going out to the street to preach, and evenings attending prayer meetings. Six months of the year they took classes at the school, six months planting churches far and wide. Moon spent six months in Gyeongseong and the other six months back in her hometown.

Reaching the unreached

She planted three churches, her first in 1932 on Imja Island, where her husband and his concubine lived. Authors, who wrote her biography based on Baek’s testimony, described that her ministry in this area was a noble expression of love, a way of forgiving her wicked husband and his concubine. In response, her husband’s descendants claim that his financial support and her status as a wealthy noblewoman in the area protected her and helped the church thrive. However, in her denominational magazine, Living Water, in 1927, she reported that she chose this place because of her compassion for the islanders who were far from the city and unable to hear the gospel.

Her second church she planted in 1935 on Jeoungdo island, the town where her in-laws lived, and her elder brother-in-law soon joined as a church member. Women and children contributed significantly to its building, carrying heavy construction materials on their heads and assisting in the construction. Mrs. Kang—who was presumed to be a servant of Moon’s in-laws—and Kang’s daughter (Kang Minju) also became church members. Unfortunately, this church faced severe trials; in 1943, during the forced dissolution of the church denomination by the Japanese for refusing shrine worship, pro-Japanese (later local Communists) looted the church. After Korea’s liberation from Japan in 1945, it took two years of legal battles to completely regain the church. Resentful Communists continued to vandalize the church; the court sentenced one of them to remain at home in self-reflection for seven years.

Finally, in 1938, she founded her third church in Daecho-ri on Jeoungdo island, where the absence of a family to protect her led to severe persecution.

Her ministry revealed a blend of Confucian and holiness traditions, fluidly oscillating across traditional boundaries of womanhood. She exemplified the compassionate mother role by assisting women in childbirth and focusing on children’s education. She made the Bible accessible to the largely illiterate women and children of her time through hymns and engaging stories. And she led personal and social holiness reforms by advocating against alcohol and gambling, collecting food from wealthy households' feasts to distribute to the poor, and caring for the sick. Meanwhile, she contested shamanism/idolatry. Influenced by shamanism, the islanders used to build shrines in the mountains to pray for safety from the frequent natural disasters. Moon displayed powerful charisma by destroying these mountain shrines and driving out bad spirits. She preached boldly to all social classes and genders, even noblemen. However, she appears not to have intervened in the contemporary systems of social and economic inequality, including slavery.

Forgotten martyr

Her ministry outraged the local Communists, mostly pro-Russian laborers. They despised a noblewoman whom they perceived to be allied with American Christianity. In particular, their grudge over a previous legal dispute branded Moon as their enemy. When the Korean War broke out in 1950 and North Korea occupied the region, the Communists arrested Moon and moved her to the People’s Court in Mokpo city. Just then, South Korea recaptured Mokpo, and she was released. However, local Communists were still holding her church members on the island. Despite having a way to live in safety herself, she returned to the island to save them, surrendering herself to the Communists. As the South Korean forces pressed onto the island, the enraged Communists brutally killed her, her husband and his concubine, and forty-eight members of her first church, including a child as young as five.

Moon lived through an era of great turmoil. She was born before Japanese colonial rule, endured it, experienced Korea’s liberation, and ultimately perished in the Korean War. Because history has tended to focus on the sacrifices and martyrdom of male ministers, her story did not come to light until thirty-five years later, prompted by her denomination. Her influence then began to spread far and wide across gender, religion, and denominations. Kang Minju became the founder and chairman of the pharmaceutical company “The Moon.” She testified that she could continue studying thanks to Moon’s influence, even during a time of severe gender discrimination. Presbyterian pastor Kim Joon Gon, founder of Campus Crusade for Christ in Korea and the National Prayer Breakfast, refers to Moon as his spiritual mother. The fact that 90 percent of her home county’s population of Sinan are Christians and the region lacks the shrines or Buddhist temples commonly seen in Korea, reveals the countless children of her faith. No wonder that South Korean President Moon Jae-in praised her as “the mother of us all and pioneer in eradicating illiteracy at the 50th Korea National Prayer Breakfast of 2018. Despite all this, due to a lack of records and inconsistent oral accounts, her story remains largely unknown—surely a call for historians to restore the voices of the voiceless.

Ranmi Bae is a PhD student in the Department of Religion at Baylor University.

To learn more about twentieth-century martyrs, see issue #109, Eyewitnesses to the Modern Age of Persecution.