Rulers of Christ's kingdom or sheep among wolves?

The kingdom of Christ in your realm—Martin Bucer True believing Christians are sheep among wolves—Conrad Grebel

“It would seem fitting to write for Your Majesty a little about the fuller acceptance and reestablishment of the Kingdom of Christ in your realm.”—Martin Bucer, Preface to De Regno Christi, addressed to Edward VI of England

“True believing Christians are sheep among wolves, sheep for the slaughter. They must be baptized in anxiety, distress, affliction, persecution, suffering, and death. They must pass through the test of fire, and reach the Fatherland of eternal rest, not by slaying their bodily enemies but their spiritual enemies...”—Conrad Grebel

Reflections by Jeffrey B. Webb, professor of American history at Huntington University

This spring I heard two commencement addresses, Donald Trump’s Liberty University speech, and C.J. Pine’s Notre Dame valedictorian speech. Both invoked faith, and both tried to apply the Gospel to our present situation. Like Martin Bucer and the Swiss Brethren nearly five hundred years ago, they seemed interested in the question of how the Kingdom of Christ might be more fully accepted and established in the secular world we live in. And yet, like Martin Bucer and the Swiss Brethren, the two arrived at very different answers.

Their differences have roots in the Reformation era. When Bucer wrote De Regno Christi in 1550, he was living in a time of political turmoil, maybe even more so than our own era of Brexit and Trump tweets. Chased from the continent, Bucer fled to England, where he took upon himself the task of instructing the boy-king Edward VI and his Regents how to build a Christian society under Christian laws—an effort he had undertaken but failed to achieve earlier in Strasbourg.

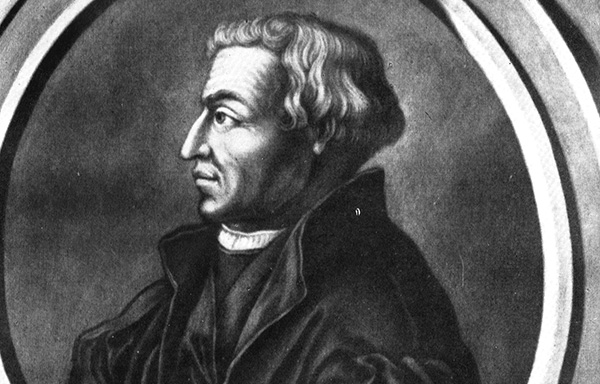

Martin Bucer

Bucer was convinced that the Bible draws us to build Christian commonwealths on earth. He thought the powers of the state should be used to achieve this end, and in his book he drew from two historical examples: Constantine in Rome and Justinian in Byzantium. To his way of thinking, the state should play a role in helping the church find its way through theological disagreement and ecclesiastical conflict, in the ancient world and in his own times.

But Reformation figures like Michael Sattler, Conrad Grebel, and Felix Manz—the Swiss Brethren—read the Bible differently. They taught that the Christian faith should be kept separate from entanglement with civil authority in order to preserve its prophetic voice. They believed Jesus taught us to be peacemakers, to love our enemies, and to welcome the stranger, which contradicted the priorities of earthly governments.

Bucer and his Swiss counterparts disagreed about how to bring Jesus’ teachings to bear on our life in common with other human beings. Times of political uncertainty just seem to draw these differences into stronger and stronger contrast. This is why I think Trump’s and Pine’s speeches are so compelling.

Trump touched on a number of topics, including Liberty’s football program and George Rogers’s WWII military service, but its overarching theme was individual and national success, best described as Christian nationalism: “As long as America remains true to its values, loyal to its citizens, and devoted to its creator,” Trump declared, “then our best days are yet to come.”

He called Liberty graduates to fight for religious freedom, using terms like “courage” and “confidence.” He told the audience to dream of a better future despite the opposition of “the cynics and the doubters.” In the final part of the speech, Trump asked them to work with him to “replace a broken establishment with a government that serves and protects the people” as a means to fulfill the nation’s “glorious destiny” at the hands of an “almighty God.” It was a speech built on his campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again.”

In a very different vein, C.J. Pine’s address spoke of a “deeper magic” of the Gospel and called his fellow graduates to “transform a kingdom of oppression through a kingdom of sacrifice.” In a passage where he alluded to working with Syrian refugees, he said, “Our hearts cannot be contained by one place, by South Bend, Indiana, or Amman, Jordan, or Tianjin, China. If we are going to build walls between American students and international students, then I am skewered on the fence.”

Pine’s address plainly invoked the life and words of Jesus: “His is a love that asks: ‘What good is it to gain the world and lose our souls?’ What good is it to have a physical security patrolled by barbed wire? His is a love that says: I came not to be served, but to serve, and to give my life for the freedom of others. His is a love that questions promises of strength with an unbending commitment to character.”

Perhaps you can hear a faint echo of the Swiss Brethren, who followed the apostle Peter in thinking of themselves as aliens and foreigners scattered throughout the world (I Peter 2:11). Where Trump strongly identified Christianity with the U.S. government, Pine envisioned the Christian faith as a global community. To his way of thinking, the Christian witness sometimes puts us at odds with particular nations and their purposes.

In times of political uncertainty, we may think it’s urgent to discern a clear path forward. But the differing voices of these Reformers teach us clarity is elusive. How do we as common citizens help to “establish the kingdom of Christ in [the] realm”? Jesus asks us to do hard things, like be generous and compassionate toward our neighbors, bless those who curse us, love our enemies, and not repay hostility with hostility. In the present season, it’s important to remember our citizenship in the kingdom of Christ and strive to live out its highest ideals in the realm in which we currently reside.

Jeffrey B. Webb is professor of American history at Huntington University and the author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Christianity

(Join us each Thursday for a fresh look at a quote from the Reformation era! Sign up via our e-newsletter (in the box at the right) or through our RSS feed (above), or follow us on Facebook through October as we celebrate 500 years of Reformation.)