The Christian Role in Ending American Slavery

A guest post by John B. Carpenter

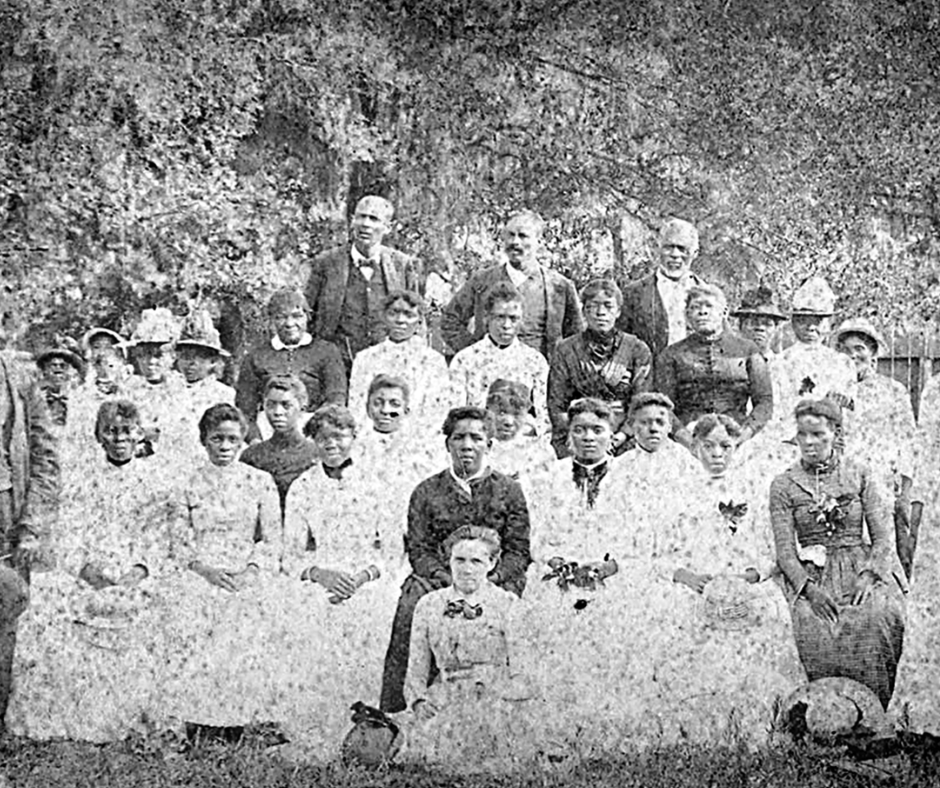

Juneteenth Celebration at Emancipation Park, Houston, 1880. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Robert W. Fogel, a self-identified “secular Jew” who won the Nobel Prize for his research on slavery, determined that it was not economics that ended slavery. Indeed, his research proved that slavery was thriving on the eve of the Civil War. The “arc of history” inevitably bending toward justice did not end slavery. Christians did.

Controversially, Fogel concluded that slavery was evil not primarily because it underfed, regularly abused, raped, mutilated, or deprived its victims of family life, a future, and property. While these atrocities did occur, they were not as widespread as abolitionists suggested. Fogel found that the greatest and underlying evil of slavery lay in the God-like dominion it exerted over its victims. Robbing workers of the fruits of their work is evil, a violation of the eighth commandment. Depriving people of the freedom to invest their lives as they see fit is evil. Forcing people to live at the arbitrary whims of others is evil. That the physical lives of slaves were not always as dire as commonly perceived does not soften slavery. Rather, it emphasizes that its fundamental evil was not economic but spiritual.

"Do unto others"

At the founding of the United States, all of the original thirteen states permitted slavery. Originally, every state was a slave state. However, as Christians increasingly recognized that American, race-based slavery differed significantly from the indentured servitude many European colonists had experienced and from the slavery described in the Bible, they began to see it as a blatant violation of the Lord Jesus’ “golden rule”: do unto others as you would have them do to you (Matthew 7:12).

As American slavery became more prominent, its true nature became more apparent. Christians began to oppose it. So arose leaders like the Quakers Moses Brown (1738 –1836), John Woolman (1720 –1772), and Benjamin Lundy (1789-1833), editor of the Genius of Universal Emancipation; and the Puritan Samuel Sewall (1652 – 1730) who authored The Selling of Joseph (1700), one of the earliest anti-slavery texts; Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803) who led his church to become the first recorded organized church to openly preach against slavery; Presbyterian pastor Jacob Green (1722-1790) identified slave-holding as contrary to the ideals of the Revolution; early Baptist leader Isaac Backus (1724-1806) declared “No man abhors that wicked practice [of slavery] more than I do”; Baptist pastor David Barrow (1753–1819) founded the Kentucky Abolition Society; Lyman Beecher (1775 –1863) championed the abolition of slavery, influencing leading abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879); George Bourne (1780–1845) a Presbyterian pastor in Virginia, authored The Book and Slavery Irreconcileable (sic) (1815); Francis Wayland (1796-1865), Baptist pastor and president of Brown University, wrote anti-slavery books which influenced Abraham Lincoln; and the many converts of the revivalism of the early nineteenth century were taught, by leaders like Charles Finney (1792-1875), that opposing slavery was a moral obligation. Hence, entire denominations officially denounced slavery, such as the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Quakers, The Reformed Presbyterian Church, The Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, Presbyterian General Assembly, Triennial Board of Foreign Missions (the, then, major Baptist organization), and others.

Debates within the Body

We must admit, as skeptics quickly remind us, that some professed Christians defended slavery until the very end. Robert Dabney (1820–1898), a Presbyterian theologian, ardently supported the oppressive institution. Such support for slavery, so late in history when slavery was on the brink of abolition, is indefensible. Dabney’s full-throated support for slavery when it was on the verge of abolition differs markedly from Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758), over a century earlier, who owned as many as four slaves. I wish he had demonstrated the same insight regarding slavery as he did in theology. However, he lived in the mid-eighteenth century, before the abolition movement had fully developed and before universal emancipation was feasible. Nevertheless, Edwards’s theology contained the seeds of emancipation. For instance, his disciple Samuel Hopkins and his son, Jonathan Edwards the Younger (1745–1801), both pioneered abolition.

When evaluating a Christian’s stance on slavery, consider their position within the history of abolitionism. Then, assess whether the trajectory of his teachings moved toward or away from emancipation. Remember that under the name “slavery” falls a wide gamut of practices. The indentured servitude that enabled many European settlers' passage to America resembles slavery. In biblical times, individuals in dire circumstances might sell themselves into slavery as a means of survival. Then there was American, race-based, perpetual slavery, partly (if not largely) based on “man-stealing” (thus incurring the death penalty according to Exodus 21:16 for anyone who possessed a slave obtained through such means). John Wesley described this peculiar slavery, “the vilest that ever saw the sun.” As American Christians realized Wesley was right, they largely turned against slavery.

Preaching freedom

As Puritanism evolved into broad evangelicalism following the Great Awakening, its values were disseminated and deeply ingrained in American culture. Imbued with those values, the physical and spiritual descendants of the Puritans carried their principles with them across the country, particularly westward into what is now the Midwest. They were determined to shape society according to Christian tenets, with the abolition of slavery as their primary objective.

Christians roused the nation to the reality that no race deserves to be enslaved, nor does any race deserve to enslave. Regrettably, some Christians were never roused. Worse, other professed Christians were opposed to the rousing. But that’s tragically normal. People often resist change, and slavery had been the status quo of history. The true miracle was that some Christians, particularly those deeply rooted in Puritanism, recognized the immorality of slavery and rallied a nation against it. Juneteenth serves as an opportunity to thank God for them and the end of slavery in our country.

For a fuller description of Professor Robert Fogel’s findings, see “How Christians Ended Slavery,” The Vital Center (May 31, 2025).

John B. Carpenter (@CovenantReform2), Ph.D., is pastor of Covenant Reformed Baptist Church and the author of Seven Pillars of a Biblical Church (Wipf & Stock, 2022) and the Covenant Caswell substack.

To learn more about Christian abolitionists, read CH issue #33, Christianity and the Civil War, which is also available for purchase.