The Extraordinary Quaker Contribution

What happens when a handful of men and women determine to obey God’s word at any cost? Only an industrial revolution and the reformation of society! by Dan Graves

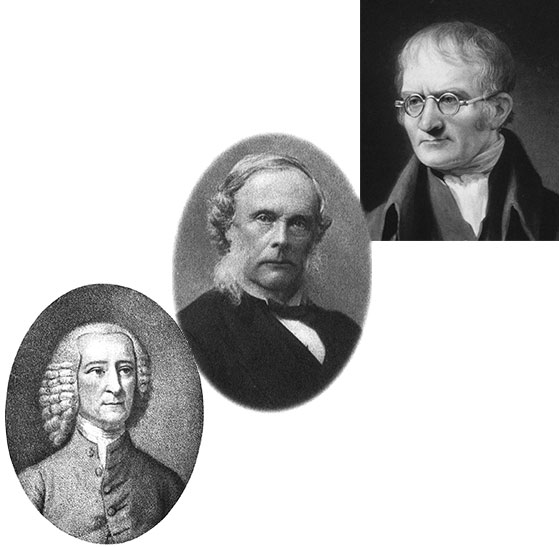

A Quaker Trio: (L-R) Fotheringill, Lister, and Dalton

SMALL AND PERSECUTED

The influence of Quakers has been completely disproportionate to their numbers. Never a large sect, they clung to radical Bible-based beliefs despite intense persecution. In doing so they transformed society. The current issue of Christian History looks in depth at the social repercussions of the Quaker movement. This blog focuses on Quaker contributions to science, technology, and medicine.

Quakerism emerged around 1650 out of the religious turmoil associated with the Puritan revolution in England. Although the sect’s official name is The Society of Friends, they have been called Quakers almost from their beginning. Judge Gervase Bennett applied it to them in mockery when Quaker founder George Fox (1624–1691) bade him tremble at the word of God. Fox’s followers accepted the the nickname as a badge of honor. Many of them could say with the psalmist, “My flesh trembles in fear of you; I stand in awe of your laws,” (Psalm 119:120).

Because Quakers refused to attend the Church of England or pay tithes to it, they were known as dissenters and subject to fines and imprisonment. At one point, when their numbers had grown to 40,000, a quarter of them—10,000—were simultaneously in prison. Hundreds died in the dismal conditions. Their lands were confiscated, their cattle seized, their property subjected to arbitrary levies. Their persecutors bored holes through their tongues, cropped their ears, or hanged them.

Undeterred, the Quakers supported one another and plodded on to prosperity. The laws that discriminated against them compelled many to become artisans, tinkers, and doctors, whose wealth consisted less in property than in skills which, with hard work, could replenish the losses of governmental confiscation.

DOCTORS OF MERCY

Among the sanctions imposed on the Quakers was disbarment from Oxford and Cambridge universities. Quakers who wished to become doctors turned to the newer University of Edinburgh. Whereas Oxford and Cambridge were steeped in Medieval medical traditions, Edinburgh accepted the new ideas of Thomas Sydenham and Hermann Boerhaave (neither of them Quakers). As a consequence, higher medical standards and a new mercifulness crept into medicine, imparted to the establishment as a whole in part through the influence of such great Quaker doctors as John Fothergill (1712–1780) and John Coakley Lettsome (1744–1815).

In due course Quakers produced one of the greatest doctors of all time, Joseph Lister (1827–1912), founder of aseptic surgery. It was his father, J.J. Lister (1786–1869) who modernized the compound microscope. J.J.’s good friend, the Quaker Thomas Hodgkin (1798–1866), discovered the neoplastic disease that bears his name. The pair gave the first true description of the shape of red blood cells.

In more recent times Len Lamerton (1915–1999) was a founder of radiation biology and a pioneer in cancer research. His co-worker G. Gordon Steel (1935–) pioneered radiotherapy and produced highly-regarded measurements of tumor development.

CAN-DO

Quakers did not just attend Edinburgh. Dissenter academies offered the world’s first modern-style science education. These had a powerful influence on the industrial revolution which was undergirded by Quakers and fellow-dissenters—and largely financed by them, too.

Driven by prejudice to utilitarian trades, a can-do streak revealed itself in the Quakers and was strengthened by adversity and conviction. It led them to dominance in the iron, steel, and coal industries—a dominance that lasted a century.

At one point, about 50% of successful entrepreneurs in England were dissenters. Among them was a Quaker named Abraham Darby (1678–1717) who experimented for years to duplicate Chinese methods of casting iron. His manufacturing firm finally solved the problems of using coke in iron making and developed continuous feed production. Another holy Quaker, Benjamin Huntsman (1704–1776), became the first man in the world to cast steel. Similarly, John Champion (1705–1794) patented new copper smelting techniques.

Quaker entreprenuer William Allen (1770–1843) founded Allen and Hanbury’s medical and chemical company as well as advancing education worldwide through the influence of his friend the educator Joseph Lancaster (1778–1838), also a Quaker.

The first westerner to produce porcelain was another Quaker, William Cookworthy (1705–1780). Much Quaker industry was devoted to the production of household wares for which they generated a new market.

EDUCATED ARTISANS

Quaker John Woolman (1720–1772) reflected in his journal, “I was taught to read almost as soon as I was capable of it.” Education was one ingredient to Quaker success. At a time when perhaps only 10% of English knew how to read, Quaker literacy stood near 100%, establishing the standard of universality that became common in the West. Children, they believed, were God’s gift to be cultivated as faithfully as any estate.

One such child, John Dalton (1766–1844), opened his own school at the ripe age of twelve, and taught other children to read and write. He spent most of his life as an educator in dissenter schools, and faithfully participated in Quaker services and meetings. Never far above poverty (it kept him from marriage) he nonetheless persisted in experimenting with chemicals. It paid off when he gave us modern atomic theory, based not on guesses but on quantification. Accepted immediately, his theory led rapidly to the measurement of atomic weights for all elements and the development of the periodic table of elements.

BEYOND DALTON

Quaker scientific contributions did not end with Dalton. In the twentieth century, Sir Arthur Eddington (1882–1944), one of the truly great figures in the formation of modern astronomical and stellar theory, was also a convinced Quaker. So was Jocelyn Bell Burnell (1943–) who co-discovered pulsars and chaired Quaker meetings.

Although he did not remain a Quaker, Thomas Young (1773–1829) was reared as one. He proved that light acts as a wave, showing that it creates interference patterns characteristic of waves when passed through a double slit. This was in addition to his linguistic work in breaking Egyptian hieroglyphic writing.

Crystallographer Kathleen Lonsdale (1903-1971) confirmed the ring structure of benzene. Like many Quakers, she was a peace activist.

BOTANICAL BOUNTY

Barred from many professions, as we have noted, Quakers also exerted their ingenuity in botany. Dr. John Fothergill and Peter Collinson (1694–1768) imported a host of new plant species to England, some for their own large gardens, some for dispersal throughout the nation. Many of their rare specimens came from America, packed by hard-working John Bartram (1699–1777), a devout Quaker, whose theology was nonetheless more Arian than Christian. The Quaker gardener Phillip Miller (1691–1771) published new and influential methods of horticulture. Between them, these men changed the plant life of their nations.

While the main influence of Quakers was on social changes such as the abolition of slavery, conscientious objection to war, extension of benefits to employees and the like, it is clear their influence in other fields was not negligible. In the Quakers we see an example of what God can do with a people who commit themselves to follow him in spite of all hardships. Such people are always viewed as a threat to the established order, but in the end the world is better for their corrective, even if it does not like to accept it.