The Reformation in Wittenberg: Part I

By Jim West

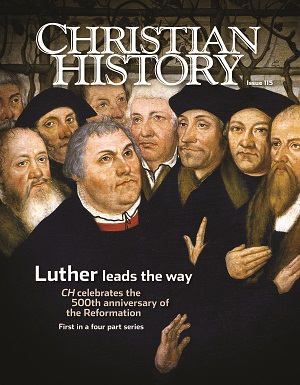

(We are publishing this essay by Dr. West in three parts over the next few weeks as part of our celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. It gives us a closer look at how Wittenberg ecountered and dealt with Luther's reforms. Read more about Luther—and Wittenberg—in our issue #115, "Luther Leads the Way.")

Johann Aurifaber, who edited Luther's "Table Talk" in 1566, concluded that "[Luther's] teachings have grown and prospered up to our own time, but from now on they will decrease and fall, having completed their appointed course".[1]

Whilst it is fairly well known how Calvin felt about Geneva and the Genevans, and how they felt about him[2], it is less widely known what Martin Luther’s attitude towards Wittenberg was. Yet the town and the Reformer are eternally and everlastingly intertwined. What was Wittenberg like when Luther lived there and how did the people of the town look upon the new Professor of Bible and his fight with Rome? How influential were Luther’s efforts and did they make any difference to the townsfolk or were they just more academic churchly squabblings which had little impact on the citizens and their daily lives?

Wittenberg’s streets were mud holes[3] when Martin Luther arrived in 1508 at the recently founded University (est., 1502-02), the brain child of the Elector of Saxony, Friedrich the Wise. As several letters which mention the city suggest, it was a dank and miserable place in the Sixteenth Century:

Melanchthon, e.g., in a letter to Camerarius, calls Wittenberg “a hamlet comprised, not of regular houses, but only of little ones, bad huts, built out of clay and covered with hay and straw.” Luther gets even crasser; he complains: “Here in Wittenberg there’s no more than a miserable corpse; we sit here in Wittenberg as if it were a miserable place.” He must have been very angry when he wrote this; for at another time he speaks more mildly: “Our land is quite sandy and has nothing but rocks, for the soil is not very fertile;” then he continues: “Nonetheless God gives us out of these rocks good wine and delicious grains, but because the miracle happens daily, we despise it.” – Duke George of Saxony (1471-1531[sic][he actually died in 1539, JW]), his religious opponent, called it a hole: “that a single monk from a hole should undertake such a reformation, is intolerable.” – And the same attitude is found in a letter from 1523, which Johann Dietenberger (1475-1537) wrote to Johann Cochlaeus (1479-1552). It says, among other things: “the poor, miserable, filthy little town of Wittenberg, compared to Prague not even worth three pennies, isn’t even worthy to be called a town in Germany; it was unknown to the learned and the commoners 20 years ago; an unhealthy, unpleasant piece of land; without vineyards; without parks; without orchards; a peasants’ chamber; rough; half-frozen; joyless; filled with muck. What’s left in Wittenberg, if the castle, monastery, and school were gone? Without a doubt, you’d only see Lutheran, that is, filthy, houses; untidy alleys; all paths, ways, and streets full of mire; a barbarian people which doesn’t do anything but farming and small trade. Their market is without people; their town is without burghers; its inhabitants wear simple garb; there’s great need and poverty of all inhabitants.”[4]

Were things really that bleak or are our correspondents simply taking the opportunity to sling a bit of mud at the Lutherans who lived in the town: a group of persons who, for the most part, were far more concerned with drinking and wenching and freedom from Church taxes than they were with Luther’s lofty theological opinions? Luther seemed to hold a fairly low view of the city after years of laboring for its betterment. His sermons are filled with excoriations of the populace for its rather lackluster interest in important theological issues. Was Wittenberg simply a town glad to have a bit of relief from Roman oppression without any real personal conviction of Lutheran truth?

Located in Saxony, due southwest of Berlin and northeast of Leipzig, Wittenberg was, in the 16th century, a hinterland; a backwater. Yet it would achieve the highest possible acclaim for such a small hamlet when it became the home of the man who would be the greatest Reformer Germany has ever known.

(Map courtesy Google Maps)

Luther’s opinion of the city in which he found himself for Doctoral studies (from which he would graduate October 18-19, 1512) is less than exuberant. He wrote, towards the end of his life in a famous letter to his wife, Katie, the following:

The day after tomorrow I shall drive to Merseburg, for Sovereign George has very urgently asked that I do so. Thus I shall be on the move, and will rather eat the bread of a beggar than torture and upset my poor old [age] and final days with the filth at Wittenberg which destroys my hard and faithful work. You might inform Doctor Pomerand Master Philip of this (if you wish), and [you might ask] if Doctor Pomer would wish to say farewell to Wittenberg in my behalf. For I am unable any longer to endure my anger [about] and dislike [of this city].[5]

The story of Luther’s work in Wittenberg is very well known so our focus will be the city itself. How did it understand the events that were taking place in it between 1517 and 1530? And how were those world changing events received or repulsed by the citizens of that town? In short, we shall examine the ‘reception history’ of the Lutheran Reformation in the city he called home from 1508 till his death nearly 40 years later.

Our methodology is a simple one: to read primary sources, chiefly letters and sermons from Luther, to discern as best we can how the Reformation was actualized in Wittenberg. Our chronological framework is the years 1517 to 1546. The year 1517 needs no justification but 1546 well might.

It is the view of the present writer that by 1546, that is, by the time Luther died, the city of Wittenberg was unalterably Lutheran. After Luther’s death it remained Lutheran and to the present it continues to identify itself with its most famous resident. In what follows we shall examine two chief sources.

Stay tuned for the next installment—Wittenberg in Luther's letters and his Table Talk.

[1] Gerald Strauss, “Success and Failure in the German Reformation,” Past and Present 67 (1975): 30–63, here p. 31.

[2] When Calvin refused to dispense the Lord’s Supper to the unworthy... “Angry cries were heard. Sticks were brandished. Swords were drawn. But the ministers were allowed to leave the building without injury, and the congregations separated without bloodshed. Next day the Councilmet and formally deposed Farel and Calvin for contempt of lawful authority, and gave them three days in which to leave Geneva. Calvin’s remark when he heard the sentence is memorable: “Well, indeed. If we had served men we should have been ill rewarded, but we serve a greater Master who will recompense us.” Every hand was now against him, and the rage of those who were exasperated by the idea of discipline foamed over.” Reyburn, H. Y. John Calvin: His Life, Letters, and Work (p. 80). London; New York; Toronto: Hodder and Stoughton, (1914).

[3] See the delightful description of Wittenberg by Gottfried Krüger in Luther: Vierteljahresschrift der Luthergesellschaft 15 (1933): 13-32. His description borders on hagiography, but it is still one of the most graphic attempts to place Luther within his town.