The Reformation in Wittenberg, part III

By Jim West

_-_Bildnis_des_Martin_Luther.jpg)

(We have been publishing this essay by Dr. West over the last few weeks as part of our celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. It gives us a closer look at how Wittenberg ecountered and dealt with Luther's reforms. Read more about Luther—and Wittenberg—in our issue #115, "Luther Leads the Way." The first post in this series can be found here and the second one here.)

Luther’s Wittenberg: The Sermons

In 1522 Luther preached to the citizens of the town a sermon which included these lines:

Here let us beware lest Wittenberg become Capernaum [cf. Matt. 11:23]. I notice that you have a great deal to say of the doctrine of faith and love which is preached to you, and this is no wonder; an ass can almost intone the lessons, and why should you not be able to repeat the doctrines and formulas? Dear friends, the kingdom of God,—and we are that kingdom—does not consist in talk or words [I Cor. 4:20], but in activity, in deeds, in works and exercises. God does not want hearers and repeaters of words [Jas. 1:22], but followers and doers, and this occurs in faith through love. For a faith without love is not enough—rather it is not faith at all, but a counterfeit of faith, just as a face seen in a mirror is not a real face, but merely the reflection of a face [I Cor. 13:12].[1]

The populace was, it seems, happy enough to hear of freedom but not so inclined to live like citizens of the heavenly kingdom.

That same year, once the Wittenbergers had begun to receive the Sacrament in both kinds, Luther’s displeasure at the behavior of the populace was even more pronounced:

I was glad to know when some one wrote me, that some people here had begun to receive the sacrament in both kinds. You should have allowed it to remain thus and not forced it into a law. But now you go at it pell mell, and headlong force every one to it. Dear friends, you will not succeed in that way. For if you desire to be regarded as better Christians than others just because you take the sacrament into your hands and also receive it in both kinds, you are bad Christians as far as I am concerned. In this way even a sow could be a Christian, for she has a big enough snout to receive the sacrament outwardly. We must deal soberly with such high things. Dear friends, this dare be no mockery, and if you are going to follow me, stop it. If you are not going to follow me, however, then no one need drive me away from you—I will leave you unasked, and I shall regret that I ever preached so much as one sermon in this place. The other things could be passed by, but this cannot be overlooked; for you have gone so far that people are saying: At Wittenberg there are very good Christians, for they take the sacrament in their hands and grasp the cup, and then they go to their brandy and swill themselves full. So the weak and well-meaning people, who would come to us if they had received as much instruction as we have, are driven away.[2]

It is more than a little difficult to know if Luther’s use of ‘dear friends’ is merely a politeness which he did not feel in his soul. His anger is on display, particularly the line “I shall regret that I ever preached so much as one sermon in this place,” extremely telling in spite of its brevity.

Luther is, in short, exceedingly disappointed in the failure of the populace to act like Christians and love like Christians. He proceeds:

Love, I say, is a fruit of this sacrament. But this I do not yet perceive among you here in Wittenberg, even though you have had much preaching and, after all, you ought to have carried this out in practice. This is the chief thing, which is the only business of a Christian man. But nobody wants to be in this, though you want to practice all sorts of unnecessary things, which are of no account. If you do not want to show yourselves Christians by your love, then leave the other things undone, too, for St. Paul says in I Cor. 11 [I Cor. 13:1], “If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal.” This is a terrible saying of Paul. “And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. If I give away all I have, and if I deliver my body to be burned, but have not love, I gain nothing” [I Cor. 13:2–3]. Not yet have you come so far as this, though you have received great and rich gifts from God, the highest of which is a knowledge of the Scriptures. It is true, you have the true gospel and the pure Word of God, but no one as yet has given his goods to the poor, no one has yet been burned, and even these things would be nothing without love. You are willing to take all of God’s goods in the sacrament, but you are not willing to pour them out again in love. Nobody extends a helping hand to another, nobody seriously considers the other person, but everyone looks out for himself and his own gain, insists on his own way, and lets everything else go hang. If anybody is helped, well and good; but nobody looks after the poor to see how you might be able to help them. This is a pity. You have heard many sermons about it and all my books are full of it and have this one purpose, to urge you to faith and love.[3]

Luther’s feeling’s about the Wittenbergers unwillingness to adopt the implications of his teaching were no different when, a decade later (in 1531 to be precise) he can declare, in a Sermon on 2 Corinthians 3,

What Paul means is that whatever good we do in preaching is done by God; when we preach it is God’s work if it has power and accomplishes something among men. Therefore if I am a good preacher who does some good, it isn’t necessary for me to boast. It’s not my mind, my wisdom, my ability. Otherwise at this hour all of you would be converted and the godless would be damned and all the wiseacres, anti-sacramentalists, sectarians, and Anabaptists who say, “The gospel in Wittenberg is nothing, because it does not make people holy,” would be checked.[4]

In 1545 Luther preached from 1 Corinthians 15 and had this to say about the citizens of his town:

Indeed, Holy Scripture has prophesied that the closer that day is, the less faith and love, and the more presumptuous security, there will be in the world. The people in Sodom and Gomorrah were just like the wicked, coarse people of our time. They sorely grieved faithful Lot with their unchaste behavior and, as St. Peter says [2 Pet. 2:8], tortured his righteous soul day after day with their unrighteous deeds. They let the good old man preach, warn, and threaten, but meanwhile they sang their drinking songs, mocking him as a fool, and did not amend their ways at any of his rebukes. Our squires, peasants, citizens, nobles, etc., do exactly the same nowadays as well. “Ha,” they said. “Let the Last Day come. We have such a long time still before the Last Day comes, so let us be greedy, practice usury, go whoring, fornicating, drinking, gorge ourselves, and live in all kinds of lusts; there is no danger.[5]

Scarcely a year before his death, preaching in the parish church, Luther remarks quite bitterly that the citizens of Wittenberg are so bereft of the influence of the Gospel that they feel no compunction about the most scandalous behavior. Even whoring, fornicating, drinking, gluttony, and lustfulness are not to be a concern[6]. God is well and truly hardly worth taking into account. Indeed, he is of no account.

The failure of his Gospel to change ‘hearts and minds’ in Wittenberg is bitterly expressed when he suggests that if the town had actually heard what he had been saying and writing then the various and sundry outsiders who were mocking the citizens (and thus, Luther’s Gospel) would surely be silenced by their proper living. In fact, what was said of Zwingli could also easily be said of Luther:

So marked was the favor shown Zwingli by the people, that his enemies had not the boldness to assert themselves. But as the new doctrines began to lose their novelty, and the first general outburst of enthusiasm began to subside, they gathered courage once more and began stealthily to attack him. The monks were especially bitter, and the ears of the canons were soon filled with complaints. Rhenanus says that of his enemies some laughed and joked, while others gave voice to violent threats. To all this Zwingli submitted with Christian patience. His devotion to music, which was as strong as ever, continued to furnish grounds for vilification. His foes dubbed him “the evangelical lute player and fifer.”[7]

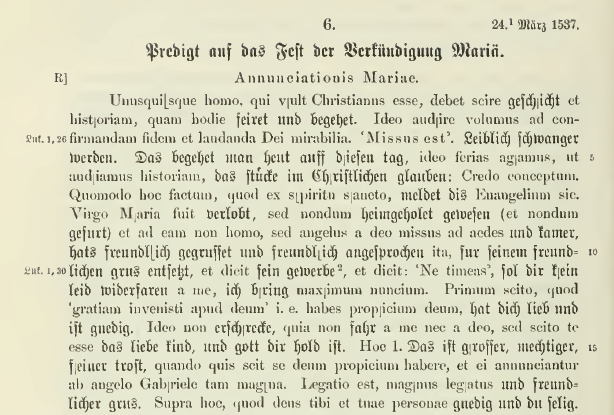

Substitute ‘Luther’ for ‘Zwingli’ and one gains a sense of what really happened in Wittenberg. But was it really the fault of the Wittenbergers that they did not fully embrace Luther’s reformatory message? After all, Luther’s sermons were in fact aimed at his fellow academics far more than the common folk of the town. Indeed, a look through the Weimar Ausgabe of Luther’s sermons show that most of the time he preached in a mixture of Latin (which the laity would not have known) and German (which they would have). In short, his sermons would have come across as both incomprehensible and confusing. The following brief passage from WA 45 will serve to illustrate the point:

The myth that Luther was a man of the people is simply a fantasy. Luther was an academic who spoke like one to his peers. What the common people knew of Luther’s sermons would have been second hand rumor and gossip. It is little wonder, then, that Luther’s preaching had little effect on the daily lives of the people of Wittenberg. They lacked the tools necessary to access and comprehend both his theology and its wider implications. And he lacked the ability to communicate in such a way in his sermons a sense of the depth of his thought in terms the laity could both appreciate and embrace.

Conclusion: The Reformation in Wittenberg- Did It Make A Difference to Wittenbergers?

Before he died Luther penned this letter (in 1545) to his dear wife Katie and it summarizes his attitude towards the town he made famous:

I would like to arrange matters in such a way that I do not have to return to Wittenberg. My heart has become cold, so that I do not like to be there any longer. I wish you would sell the garden and field, house and all. Also I would like to return the big house to my Most Gracious Lord. It would be best for you to move to Zölsdorf as long as I am still living and able to help you to improve the little property with my salary. For I hope that my Most Gracious Lord would let my salary be continued at least for one [year], that is, the last year of my life. After my death the four elements at Wittenberg certainly will not tolerate you [there]. Therefore it would be better to do while I am alive what certainly would have to be done then. As things are run in Wittenberg, perhaps the people there will acquirenot only the dance of St. Vitus or St. John, but the dance of the beggars or the dance of Beelzebub, since they have started to bare women and maidens in front and back, and there is no one who punishes or objects. In addition the Word of God is being mocked [there]. Away from this Sodom!

Luther surely would not have been so disgusted by the place had he felt he had done any good there. Was he correct? Yes, and no. Yes, he was correct in that the people of Wittenberg never did really fully embrace Reform as fully as Luther did. But who would, or could? And no, he was not right because the years have proven Wittenberg to be a faithful bastion of Lutheran thought (albeit imperfectly implemented). Luther had very high hopes for the Reformation in his town. Those hopes were, unfortunately, dashed on the rocks of historical reality and the personal unwillingness of the population to do what had to be done.

Luther wanted Wittenberg to be reformed. The people of Wittenberg just did not wish it so much themselves. Luther and Wittenberg are inextricably and genetically connected, but not because the populace embraced Luther’s ideas. Wittenberg was a Lutheran town when Luther was buried but its inhabitants were Lutheran for the sake of convenience and geography. They would have been papists had the papacy given them the ‘freedom’ (i.e., license) Luther’s Gospel had.

The Reformation in Wittenberg was a theological failure[8], or at least a failure in terms of having an effect on the actual daily lives of the citizens of that hovel. It was, however, on the other hand, a political success. Wittenberg from 1521 forward was firmly under the sway of what would come to be called Protestant Princes. Those Princes leveraged their famous Professor’s name to influence politics for decades if not centuries to come. Luther’s accomplishment, then, in Wittenberg itself was the establishment of a powerful political Protestant dynasty. The Pope in Rome, the Antichrist (in Luther’s view), the political force par excellence of the 16th century, was ‘overthrown’ and his authority assumed not by Luther and his Lutherans but by Protestant Princes – a new breed of Popes wielding ultimate authority over both the souls and bodies of their principalities.

Or, to borrow and adapt a phrase from Mel Gibson’s The Patriot, they traded one tyrant 500 miles away for 500 tyrants a mile away. That, tragically, and ironically, is Luther’s most lasting legacy in Wittenberg. It certainly was not Lutheran theology, as evidenced from a visitation report:

All the people hereabouts engage in superstitious practices with familiar and unfamiliar words, names, and rhymes, especially with the name of God, the Holy Trinity, certain angels, the Virgin Mary, the twelve Apostles, the Three Kings, numerous saints, the wounds of Christ, his seven words on the Cross, verses from the New Testament.... These are spoken secretly or openly, they are written on scraps of paper, swallowed (eingeben) or worn as charms. They also make strange signs, crosses, gestures- they do things with herbs roots, branches of special trees they have their particular days, hours and places for everything, and in all their deeds and words they make much use of the number three. And all this is done to work harm on others or to do good, to make things better or worse, to bring good or bad luck to their fellow men.[9]

Strauss laconically concludes, and we shall allow him the last word here as well,

Sixteenth-century theologians could not understand this. But to us, looking back, it should not appear astonishing that these ancient practices touched the lives of ordinary people much more intimately than the distant religion of the Consistory and the Formula of Concord. The deep current of popular life whence they arose was beyond the preacher's appeal and the visitor's power to compel. The permissive beliefs of medieval Catholicism had absorbed these practices and allowed them to proliferate; but this accommodating milieu was now abolished. Hostile religious authorities showed themselves unbendingly intolerant of deeply ingrained folkways. The persistence of occult practices in popular life is therefore certainly a cause, as well as a symptom, of the failure of Lutheranism to accomplish the general elevation of moral life on which the most fervent hopes of the early reformers had been set.[10]

[1] Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 51: Sermons I (ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann; vol. 51; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 71.

[2] Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 51: Sermons I (ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann; vol. 51; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 91.

[3] Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 51: Sermons I (ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann; vol. 51; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 95–96.

[4] Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Vol. 51: Sermons I (ed. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, and Helmut T. Lehmann; vol. 51; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999), 224–225.

[5] Martin Luther, “The Third Sermon: On the Last Trumpet of God [1 Corinthians 15:51–53],” in Luther’s Works: Sermons V (ed. Christopher Boyd Brown; trans. Mark E. DeGarmeaux; vol. 58; Saint Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House, 2010), 145–146.

[6] As Ralph Keen points out, this is “exactly what the Catholics predicted when obedience to the Law was removed as an incentive for salvation”. [Personal communication, 23/9/2016].

[7] Samuel Simpson, Life of Ulrich Zwingli: The Swiss Patriot and Reformer (New York: Baker & Taylor Co., 1902), 79–80.

[8] On the decades old question of the failure or success of the Reformation in Germany, see Gerald Strauss, “Success and Failure in the German Reformation,” Past and Present 67 (1975): 30–63; Luther’s House of Learning: Indoctrination of the Young in the German Reformation (Baltimore, 1978). See also Geoffrey Parker, “Success and Failure during the First Century of the Reformation,” Past and Present 136 (1992): 43–82.

[9] Strauss, p. 63.

[10] Ibid.