The Reformation of Marriage

"My mind is adverse to wedlock, because I daily expect [to suffer] the death of a heretic." - Martin Luther

Reflections by Frank A. James III, president of Biblical Theological Seminary

It is a remarkable fact that none of the leading Protestant reformers ended up a bachelor—Luther, Zwingli and Calvin all married in the course of the Reformation. It is remarkable because the prevailing late medieval ideal was that one should not marry in order to devote full attention to serving God. The same ideal prevailed for women. St. Jerome, writing in the fourth century, even offered a kind of algorithm for measuring one’s devotion to God. He assigned a spiritual value of 100 to virginity, but to marriage he assigned a paltry spiritual value of 30. The message was clear: if you really loved God, you would remain a bachelor or bachelorette.

The Reformation is most often identified with theological debates, whether over justification by faith alone, predestination, or the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. However, it can be argued that the most enduring consequence of the Reformation was not theological developments, but the transformation of the institution of marriage. By 1520, just three years after the 95 Theses, Luther publically renounced clerical celibacy in his famous pamphlet, To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation.

Although Luther remained celibate in these early years, others took his advice and leaped at the opportunity to abandon celibacy. While Luther was living incognito in the Wartburg castle, his fellow Wittenberg priest and university colleague Andreas Karlstadt married. The 36-year old Karlstadt married 15-year old Anna von Mochau, daughter of a poor nobleman in January 1522. The next month, Justus Jonas, another of Luther’s colleagues, followed suit and married. Suddenly, married clergy were all the rage—for everyone except Luther.

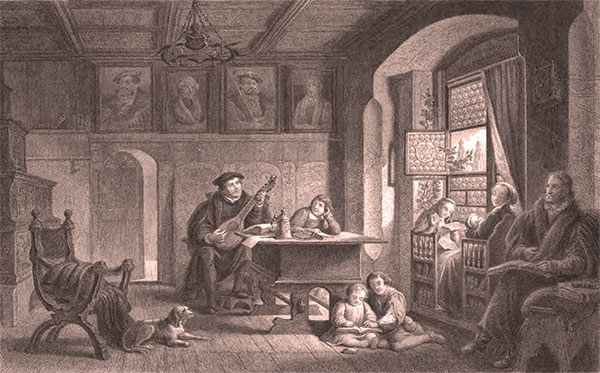

Luthers at home with Melanchthon as guest.

While approving these particular clerical marriages and generally upholding the right of clergy to marry, Luther was reticent to take the plunge himself. “I will never take a wife,” Luther declared to his friend Spalatin on 30 November, 1524, “not that I am insensible to my flesh…, but my mind is adverse to wedlock, because I daily expect [to suffer] the death of a heretic.” And then he encountered the indomitable Katie von Bora in 1524.

Following the customs of the time, Katie had been placed in the Cistercian convent of Nimbschen at ten years old. She appears to have accepted her life until she and several nuns secretly read Luther’s On Monastic Vows in 1521. The nuns embraced Luther’s rejection of clerical celibacy and turned to Luther himself to aid in their escape. With the assistance of Leonhard Koppe, twelve nuns were smuggled out of the Nimbschen nunnery in herring barrels in April 1523. Three of the fugitive nuns returned to their families, but Koppe delivered the remaining nine to Luther’s doorstep in Wittenberg. Remarkably, he found husbands for all except Katie von Bora. When prospective husbands failed to materialize, Katie took matters into her own hands and specifically suggested marriage to Luther.

Katie’s timing was just right. Luther had begun to feel the loneliness of bachelorhood, and he expressed his willingness to “take pity” on poor Katie. They married on 13 June, 1525. For Luther marriage to Katie was an act of theological defiance—“to spite the pope.” Frankly, he did not marry for love. To his friend Amsdorf, Luther confessed: “I feel neither passionate love nor burning for my spouse.” Then a remarkable thing happened after Luther married: he fell in love with his wife. Luther wore his affection on his sleeve, saying later: “I love my Katie; yes I love her more dearly than myself.” Luther and Katie enjoyed a feisty, vibrant, and openly affectionate twenty-one-year marriage relationship that produced six children.

Luther’s marriage was deeply enriching. But even more significant was the fact that Luther’s marriage, because it was such a public one, became the model for a new Protestant understanding of marriage. Indeed, scholars have argued that Luther inaugurated a cultural paradigm shift in the very concept of marriage. For centuries, marriage had been entangled with dowries and social status. But Luther was a heretic and Katie was a runaway nun with no material goods. While marriage was not disentangled from money overnight, now forefront in the Protestant ideal was the concept of mutual affection and marriage as a suitable avenue for growth in holiness. Luther and Katie changed the way the Western world thought about marriage.

Frank A. James III is President and Professor of Historical Theology at Biblical Theological Seminary, Hatfield, PA. He is the editor or author of nine books including Church History: Pre-Reformation to the Present (Zondervan) and Peter Martyr Vermigli and Predestination (Oxford University Press). Frank is a featured presenter in the award-winning documentary This Changed Everything.

(Join us each Thursday for a fresh look at a quote from the Reformation era! Sign up via our e-newsletter (in the box at the right) or through our RSS feed (above), or follow us on Facebook through October as we celebrate 500 years of Reformation.)