Article #23

“All glory, laud, and honor, to thee, redeemer, king.” Theodulf of Orléans (<em>ca.</em> 760–821), in “All Glory, Laud, and Honor.

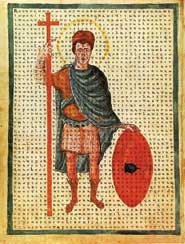

Louis the Pious, who imprisoned Theodulf

All glory, laud, and honor

Life, which has cast both smiles and frowns on Theodulf, now frowns. He is facing imprisonment in the year 818. As a refugee from Spain, which was overrun by Moorish conquerors in the eighth century, Theodulf had made his way to Italy where he became an abbot, and from there he moved on to the court of Charlemagne.

Always on the lookout for literary talent, Charlemagne appointed him bishop of Orleans. Theodulf wrote poems and epitaphs for state occasions and served as scholar, church reformer, educator, and theological advisor to the Frankish emperor. His writings included sermons and theological treatises on baptism and the Holy Spirit. He opposed the use of icons and revised the text of the Bible. But following Charlemagne’s death in 814, his sons squabbled over his empire, which began to tear apart.

Now, in 818, one of these sons, Louis the Pious, suspects Theodulf of conniving with an Italian rival. He strips Theodulf of his honors and orders him to a monastery in Angiers on the River Maine.

The walls of Saint-Aubin seal him in. Lost to him is his personal estate at Germigny. Lost is the radiant chapel he built there. No more will he be called to direct the church or write epitaphs for the imperial court.

There is, however, a greater emperor by far, to whom he can appeal and from whom earthly rulers can never deny him access. He need never lose this other emperor’s favor. Walls cannot shut him out. However much Theodulf bemoans the injustice done to him, he can still laud the King of Kings. In his monastic cell, he composes the verses of one of the greatest paeans ever written to our savior:

“All glory, laud, and honor

to thee, redeemer, king

To whom the lips of children

made sweet hosannas ring.”

Within four years of the start of his imprisonment, Theodulf dies. More than a thousand years later, an English translation of his hymn will remain a favorite in the church’s Palm Sunday festivities.

—Dan Graves

Dig a Little Deeper

- Brown, Theron and Butterworth, Hezekiah. The Story of the Hymns and Tunes. New York: George H. Doran, 1905.

- Cabaniss, Allen. Charlemagne. New York: Twayne, 1972.

- Loffler, Klemens. “Theodulf.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton, 1912.

- Sot, Michel. “Theodulf of Orleans” in Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, edited by André Vauchez, Richard Barrie Dobson, and Michael Lapidge Translated by Adrian Walford. Routledge, 2001.

- “Theodulf.” Encyclopedia Britannica. 1967, 1911.

- “Theodulf.” Encyclopedia Orbis Latini. http://www.orbilat.com/Encyclopaedia/T/Theodulf.html

- “Theodulf.” The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone. Oxford, 1997.

Next articles

Article #24: We did not know where we were

Russian Ambassadors (987), in a report to Prince Vladimir of Kiev.

Article #25: You exist so truly, Lord

Anselm (1033–1109), in Proslogion.

Article #26: God wills it!

Franks at Clermont (1095). Shouted in response to Pope Urban II.

Article #27: The death of the pagan

Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), from In Praise of the New Knighthood.