Article #15

“Our hearts are restless, until they can find rest in you.” Augustine of Hippo (354–430), in Confessions.

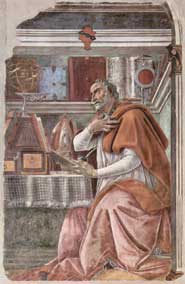

Augustine by Sandro Boticelli

Our Hearts are Restless

Behind Augustine are a succession of desperate searches for fulfillment: excessive pleasures, false religions, philosophy, dissipation and distractions—futilities that left him so weary of himself he could only cry out, “How long, O Lord, how long?” At the very moment when he uttered that cry, circumstances led his eyes to a passage in Romans that showed him he could be freed from sin. Shortly afterward, he was baptized.

Now, a decade since his baptism, after long musing upon the transformation that took place in him when he finally believed, he begins a unique autobiographical and philosophical prayer to God, a book which will become one of the most original and famous works in all of literature, the world’s first psychological “autobiography.” The Confessions will be his testimony of God’s interaction with a soul that has found rest in its Creator.

Heart bursting with the reality of God, he addresses his manuscript directly to the Lord as one long prayer and meditation—a prayer and meditation that will take him five years to complete. He dips his quill and begins, “Great are you, O Lord, and greatly to be praised; great is your power, and your wisdom is infinite.”

In contrast to God, he muses, what is man? Yet there is a connection between the two. Humans, such a small part of creation and short-lived as they are, still find a need to praise God. In spite of sin, each feels the longing to reach out to his Creator. Why is this? He realizes it is the doing of God. “You have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless, until they can find rest in you.”

That line summarizes the theme of Augustine’s life and will not be bettered in all the writings that lie ahead of him, in which he will wrestle with the deepest issues of theology.

—Dan Graves

Dig a Little Deeper

- Aland, Kurt. Saints and Sinners: Men and Ideas in the Early Church. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1970.

- Augustine. Confessions, translated by Rex Warner. New York: Mentor, 1963.

- ————. The City of God, edited with an introduction by Vernon J. Bourke. Garden City, New York: Image, 1958.

- “Augustine, St.” Dictionary of Scientific Biography,edited by Charles Coulston Gillispie. New York: Scribner’s, 1970.

- Bowie, Walter Russell. Men of Fire. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1961.

- Copleston, Frederick. A History of Philosophy. London: Burn, Oates & Washbourn, 1951.

- D’souza, Dinesh. The Catholic Classics. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, 1986.

- Dunham, James H. The Religion of Philosophers. Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1969, 1947.

- Portalie, Eugene. “Works of St. Augustine of Hippo.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton, 1914.

- ————–. “Augustine, Life of Saint.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton, 1914.

- Russell, Bertrand. Wisdom of the West. New York: Fawcett, 1964.

Next articles

Article #16: Always Have Some Work on Hand

Jerome Heironymus (ca. 342–420), in a letter to Rusticus.

Article #17: Ill fortune is of Greater Advantage

Boethius (ca. 470–524), in The Consolation of Philosophy.

Article #18: Prefer nothing whatever to Christ

Benedict of Nursia (ca. 480–ca. 550 ), in his Benedictine Rule.

Article #19: Precursor of Antichrist

Gregory the Great (ca. 540–604), in his official correspondence.