“What is Darwinism?”

Charles Hodge (1797–1878)

In his Systematic Theology (1871–1873), Hodge, professor of Oriental and biblical literature at Princeton, made four arguments for why Darwinism was untrue and unacceptable for Christians. One, it offended humans’ common sense to be taught that “the whale and the humming-bird, man the mosquito, are derived from the same source.” Two, the theory posed that the complexity of nature could arise without an intelligence directing it. Three, the theory utterly discounted religious convictions. Four, the theory could not be proven, because the origins of life could not be observed scientifically.

Hodge’s rejection of Darwinism contrasted with Princeton University’s president James McCosh’s (president, 1868–1888) beliefs that the theory would be someday proven and Christians needed to adapt their thinking to it. Until the seminary took a modernist turn in 1929, American Presbyterians received two intellectual lineages from their flagship educational institutions. The university advanced the idea that evolution was God’s way of working in nature, while the seminary taught that faith in biblical inerrancy necessitated rejection of Darwin.

Asa Gray (1810–1888)

In an 1879 letter, Charles Darwin wrote, “It seems to me absurd to doubt that a man may be an ardent theist & an evolutionist.” Darwin knew these beliefs could be compatible because both were held by his longtime friend and champion Asa Gray.

Gray, a noted botanist, taught at Harvard alongside Louis Agassiz. He met Darwin at Kew Gardens in London in 1838 and began correspondence with him in 1855. Gray had developed similar ideas on his own and was immediately convinced by Darwin’s theory. He even arranged for the American publication of Origin of Species.

But Gray disagreed with his English friend on the subject of religion, repeatedly trying to convince Darwin that his system left room for God’s design and occasional intervention. Darwin demurred. Nonetheless, Gray included his theistic synthesis when he promoted Darwin’s ideas—efforts that greatly aided the acceptance of evolution in America.

Louis Agassiz (1807–1873)

Louis Agassiz’s career illustrates key differences between nineteenth-century and modern science. Born in Switzerland, the son and grandson of Protestant preachers, Agassiz studied botany, medicine, geology, zoology, and other subfields of what was then known as “natural history.”

His first publications cataloged freshwater fish; next he moved on to glaciers and became the first scientist to argue for an Ice Age. After this, he completed a comprehensive, annotated list of the botanical genera and group names for all known animals. Invited to Boston in 1846 to deliver a lecture series on “The Plan of Creation as Shown in the Animal Kingdom,” he decided to stay, becoming a professor at Harvard.

Agassiz’s wide-ranging expertise—his subsequent lecture series ranged from “Comparative Embryology” to “Deep Sea Dredging”—contrasts with twenty-first-century academic specialization. His centrality to the American scientific enterprise cannot be matched now. A generation of scientists worked with him.

Agassiz was one of the last scientists of international repute to deny Darwinism. He rejected the theory on both scientific and philosophical grounds, maintaining until his death that different species were separate, special creations of God.

B. B. Warfield (1851–1921)

Warfield, another Princeton Seminary theologian, occupied a middle ground between McCosh and Hodge. In 1916 he recalled his days as a Princeton University student: “[McCosh] did not make me a Darwinian, as it was his pride to believe he ordinarily made his pupils. But that was doubtless because I was already a Darwinian of the purest water before I came into his hands....

“In later years I fell away from this, his orthodoxy. He was a little nettled about it and used to inform me with some vigor—I am speaking of a time 30 years agone!—that all biologists under 30 years of age were Darwinians. I was never quite sure that he understood what I was driving at when I replied that I was the last man in the world to wonder at that, since I was about that old myself before I outgrew it.”

What Warfield “outgrew” was a purely naturalistic version of Darwinism with no supernatural design or intervention. He was concerned that evolution had cost Charles Darwin his Christian faith. But Warfield did not think all Christians must suffer that fate. He left the question of his own views slightly open, stating, “I do not think that there is any general statement in the Bible or any part of the account of creation . . . that need be opposed to evolution.”

George Mccready Price (1870–1963)

The course of this pugnacious Canadian’s life was set when, after the 1882 death of his father, his mother joined the Seventh-day Adventists. The church had arisen some decades earlier under the leadership of visionary Ellen G. White (1827–1915).

Adventists worshiped on Saturday, considering it the biblical Sabbath, and were known for their emphasis on health and diet. White strenuously opposed evolution: “There is no ground for the supposition that man was evolved by slow degrees of development from the lower forms of animal or vegetable life. Such teaching lowers the great work of the Creator to the level of man’s narrow, earthly conceptions.” Her visions emphasized a literal seven-day creation, and she argued that due to the flood, “Geology cannot tell us the age of . . . fossils; only the Bible can.”

Price became a leading interpreter of White’s views to outsiders, writing many articles and over 30 books. He taught at Adventist colleges and spent four years in Britain, where he debated British rationalist Joseph McCabe in 1925 in an exchange inspired by the Scopes Trial. Price maintained that “true” inductive science would keep facts and theories distinct and that evolution remained an unproven theory.

Joseph leConte (1823–1901)

Chemist and geologist Joseph LeConte began life as a solid son of the South. Born on a Georgia plantation, he helped manufacture medicines and nitre for the Confederacy, then left his teaching post at the University of South Carolina in part to escape Reconstruction. Upon landing at the University of California, he began to model his own theory of “continuous and progressive change.”

LeConte described himself as “an evolutionist, thorough and enthusiastic . . . not only because it is true, and all truth is the image of God in the human reason, but also because of all the laws of nature it is . . . the most in accord with religious philosophic thought. It is, indeed, glad tidings of great joy which shall be to all peoples.”

At the urging of famed preacher Henry Ward Beecher, LeConte published his perspective on Darwinism in Evolution: Its History, its Evidences, and its Relation to Religious Thought (1888). LeConte’s perspective on Christianity is harder to discern. He noted in his autobiography, “So far as churches are concerned, I could never take a very active part in any, because it seems to me that they are all too narrow in their views. But recognizing as I do that they represent the most important of all human interests, I have always very cordially supported them all.”

Arnold Guyot (1807–1884)

Like his friend Agassiz, Guyot was born in Switzerland, studied widely at a number of European universities, and examined Alpine glaciers. Eventually, political revolutions caused Guyot to follow Agassiz to the United States, where he set up weather stations and revised geography curricula before securing a faculty position at Princeton University in 1854.

He spent the rest of his career there, traveling during vacations to map and measure the Appalachian Mountains. Union forces used his maps during the Civil War. Two peaks along the Appalachian Trail bear his name, as does a mountain in Colorado.

Although Guyot insisted on the special creation of matter, life, and humans, he worked to harmonize the new science with his Christian faith in Creation, or the Biblical Cosmogony in the Light of Modern Science (1884). The plaque honoring Guyot at Princeton describes him as “a devout student of nature who loved to trace the wisdom and goodness of God in the works of creation.”

Guyot made his most lasting contribution in meteorology. His plan to arrange observation stations around the country to aid in predicting storms laid the foundation for the National Weather Service.

Alexander Winchell (1824–1891)

The founders of Vanderbilt University thought they had achieved a coup when in 1875 they offered a chair in geology, zoology, and botany to Alexander Winchell—scientist, author, speaker, and preeminent interpreter of science for the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Winchell cautiously embraced Darwinism, writing in Sketches of Creation (1870) that if the theory withstood scrutiny, it would be “the duty of the Christian world to embrace it and convert it to their own uses. To do otherwise is to earn the contempt of those who are really on the side of truth.”

Winchell thought that evidence of evolutionary development displayed the unity of nature and the design of its creator. This theistic evolution was fine at Vanderbilt, but Winchell’s ideas about race were not. His theory that whites and African Americans descended from different Adams led to his 1878 dismissal. Winchell found many supporters in the North and finished his distinguished career at the University of Michigan.

James Woodrow (1827–1907)

“If Uncle J. [James Woodrow] is to be read out of the Seminary,” wrote a young Woodrow Wilson to his sweetheart in 1884, “Dr. McCosh [president of Princeton University] ought to be driven out of the church, and all private members like myself ought to withdraw. . . . If the brethren of the Mississippi Valley have so precarious a hold upon their faith in God that they are afraid to have their sons hear aught of modern scientific belief, by all means let them drive Dr. Woodrow to the wall.”

The future president’s uncle, a Presbyterian minister, served as Perkins Professor of Natural Sciences in Connexion with Revelation at Columbia Theological Seminary in South Carolina. In his 1861 inaugural lecture, he affirmed the literal truth of the Bible and assured his listeners that no scientific discoveries—including those of geologist Charles Lyell, but not yet Darwin, whose work was practically unknown in the American South—could contradict the Scriptures.

But by the 1870s, Woodrow had come to accept aspects of Darwinism. He decided that Adam’s body had resulted from evolutionary processes, though Adam’s soul and, curiously, Eve’s body, were divine creations. This led to a series of investigations that ultimately forced Woodrow from his job. He continued to teach at the University of South Carolina, where Columbia students—with the permission of their home presbyteries—continued to take his classes. CH

By Elesha Coffman and the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #107 in 2013]

Elesha Coffman, former managing editor of Christian History, is assistant professor of church history at the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary.Next articles

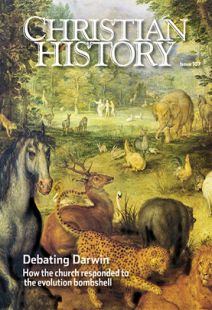

Editor’s note: Debating Darwin

History turns out to be more complicated than we expect

Jennifer Woodruff TaitDivine designs

Conservative Christians moved from cautious consideration of Darwin to outright rejection

Edwin Woodruff Tait