Tolerant and pious

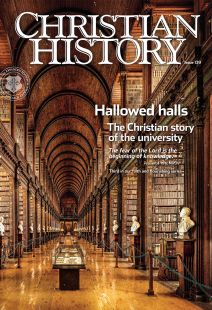

[ABOVE—Universitätsplatz, Halle (Saale), Saxony-Anhalt, Germany—PaulT (Gunther Tschuch) / [CC BY-SA 4.0] Wikimedia]

Students who refused to study, syllabi long outdated, professors more focused on research than building student character—these could be modern complaints on “Rate My Professor,” but they come from a seventeenth-century philosopher and legal scholar.

His name was Christian Thomasius (1655–1728), and in Suggestions for Establishing a New Academy, he lamented the state of almost all German universities in “the darkened condition of our time.” Though not the only one to complain, he was one of a small group who turned complaints into action by helping to found a new university in Halle more to his liking.

The first reform university

Founded in 1694, Halle ranks as the fourth oldest university within Brandenburg-Prussia. But its true importance lies in its identity as the first reform university in the German Empire, a model for other German Protestant universities.

After the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), the empire’s educational institutions suffered widespread decline. Scholars describe German universities of the day as ailing and disreputable, hardened against change and lacking in creative intellectual impulses. Thomasius and Halle’s other founders rejected the privileged position of abstract and speculative theology, and oriented knowledge to practical application and usefulness in ways that would benefit society as a whole.

Thomasius did not operate alone. Pietism, a movement that emphasized personal religion, suffused Halle’s early development and owed much to Philipp Jakob Spener (1635–1705). Provost of Berlin’s Nicholas Church, he influenced the appointment of Pietist professors, aiming to reform theological education and develop ethical pastors who could act as models for believers. Theology at Halle veered away from polemics and toward the biblical and pastoral. All of this set Halle apart from other German universities until about 1730.

Halle’s young professors faced growing antagonism from the town’s orthodox Lutheran clergy who distrusted the Pietist emphasis on personal religion. But, marked by innovation and intellectual freedom, Halle soon became an attractive choice for students, evident in its impressive numbers. Within a few years, the university grew to over a thousand students, one of the largest in the German Empire.

Halle welcomed students from all over Europe. While the majority were from Magdeburg, they also came from central Germany, free imperial cities, Friesland, Schleswig, Norway, and England. In a 1690 letter, the Magdeburg mayor extolled Halle’s advantages and perhaps helped to explain the school’s rapid growth: a well-situated and attractive place with friendly residents, plenty of fairly priced housing, and cheap food and drink. Halle would prove to be a perfect university town.

Care for poor students

Thomasius owed his opportunity as Halle’s first professor (beginning in 1690, before the official founding) to Brandenburg elector Friedrich III (1657–1713), known as “crooked Fritz” after a childhood accident left him with a twisted spine and humped back. The elector had already supported Thomasius after he escaped arrest in Leipzig. Thomasius’s views on law and religion, and his willingness to teach in German, had led him to be attacked from pulpits and forbidden to spread his opinions.

Even before Thomasius’s involvement, Friedrich desired a Lutheran university marked by moderation and tolerance, not the polemics of Wittenberg (pp. 23–25) and Leipzig (pp. 20–22). Of first concern, however, was the need for social renewal after the Thirty Years War—through a university oriented toward practical needs, educating teachers and doctors, and providing legal training for civil servants. When the university officially opened on July 11, 1694, it became known as Friedrichs University or the Fridericiana after its patron.

Halle made higher education available at low cost, with free meals for poorer students subsidized by a quarterly collection in local churches ordered by the elector. After the creation of an orphanage and schools in Glaucha in 1698, students served in the orphanage schools in exchange for free accommodation.

Over the next four decades, the university benefited from the reforming work of both Thomasius and prominent Pietist leader August Hermann Francke (1663–1727). Thomasius and Francke had been good friends at Leipzig University; Thomasius provided legal services to Pietist students in Leipzig connected to Francke when they came under attack from civic and church authorities.

In Halle Francke served as confessor to Thomasius and his family. The two shared much. Thomasius had sympathy for the Pietist practice of gathering in homes for mutual edification. He also shared the Pietist interest in encouraging the laity to nurture their own religious experience.

Both Thomasius and Francke aimed at producing graduates who would be both tolerant citizens and pious Christians; against pedagogy of the day, they emphasized education as character-building. They broke with centuries-long precedent by holding their university lectures in German rather than in Latin for wider educational opportunity, and both published in the German language so their writings would be accessible to the widest possible readership.

In his Suggestions Thomasius offered several guidelines for education reform, later put into practice. First, professors should avoid unnecessary quarrels and battles of words and teach only what contributes to human happiness and general usefulness; second, professors should use the German language; finally, professors should be chosen not so much on the basis of their writings as on account of their excellent manner of teaching.

Miserable students

Despite his lofty aspirations, Thomasius resembled modern professors in his disillusionment with students’ lack of discipline. In On the Miserable Condition of the Students (1693) he observed:

During my fifteen years of university teaching, I have found among most of my students very little diligence and seriousness in study. . . . It bothers me not a little when I see in many not only little fear of God, but also that they have never read the first five books of Moses in the Old Testament, not to mention the stories of Jesus.

Meanwhile, through Spener’s intervention, Francke had been called as pastor of St. George’s Church in Glaucha and as professor of Greek and Hebrew at the new university. Francke preached his first sermon in February 1692; a week later he held his first university lectures in the philosophy faculty. He too wanted to reform the modern student. In Timothy as the Model for All Students of Theology (1695), he reflected:

Unfortunately, student life as led in most cases in the universities, even by those who call themselves students of theology, is a truly heathen, devilish life. There is nothing more contrary to the rules of Christ than the maxims and rules they have among themselves.

Students of theology must forsake this godless manner of life and follow the rules of Christ, he believed, even if they were despised and mocked for it.

In Portrait of a Student of Theology (1712), Francke argued that students should read only what contributes to a true, genuine Christianity, especially Johann Arndt’s True Christianity (1610). Of first concern, he argued, is not quantity of reading but understanding what one reads and applying it to one’s life. Finally, he said, if students have never had a conversion experience, they should pray to be thoroughly converted.

As he taught the Bible in small academic seminars, or collegia, Francke explained that it was not enough to practice historical criticism of Scripture; one must become more godly through one’s reading and study of Scripture, just as someone who walks in the sunshine feels warmed by it.

Francke’s Pietism was not limited to the theology faculty. His practical program for universal social reform took shape in the Halle Foundations: an orphanage, schools for children from different social classes, printing and publishing houses, a mission society, and a pharmacy for medicine production—all under the patronage of the Prussian state.

Thomasius ultimately viewed Halle’s university not as the work of human ingenuity but of divine providence. Certainly it brought forth rich fruit in many respects—in the church, in the state, in scholarship, and in the German language. For generations to come, leading pastors, teachers, and Prussian state officials were products of Friedrichs University in Halle. CH

By Douglas H. Shantz

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #139 in 2021]

Douglas H. Shantz is professor emeritus of classics and religion at the University of Calgary, author of An Introduction to German Pietism: Protestant Renewal at the Dawn of Modern Europe, and editor of A Companion to German Pietism, 1660–1800.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: Godly learning, godly teaching

Christians through the centuries have wrestled with how to educate moral and virtuous people. Here are some milestones along the way.

the editors