Delicate balance

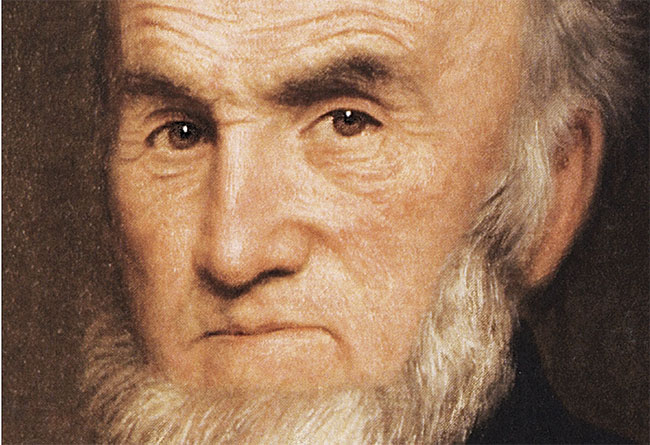

[ABOVE—Jonathan Blanchard Portrait—Buswell Library Special Collections / Courtesy of Wheaton College]

In 1994 history professor Mark A. Noll (b. 1946) published a famous lament, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. The problem, he said bluntly, “is that there is not much of an evangelical mind.” He and others wondered: how can American evangelicals relate to higher education? How can evangelical schools navigate between constituencies suspicious of change, and faculty and students trying to refine the bounds of their traditions and sometimes overstepping them? Wheaton College has tried to navigate this delicate balancing act in its 160 years of educating young evangelicals.

Christ is coming back

In its early years, Wheaton was an outlier largely for being too progressive in the eyes of the era’s conservative Christians. Jonathan Blanchard (1811–1892), the school’s 1860 founder, was a militant biblicist, but also out of step with most of the country in being a radical abolitionist. Early Wheaton looked a lot like Oberlin (see pp. 43–45); both schools welcomed women and Black students. Blanchard also opposed Freemasonry as a false religion—a stance at odds with many of America’s elite.

Charles Blanchard (1848–1925) succeeded his father as president of Wheaton in 1882 and took the school’s radicalism in a new direction. Active in Chicago evangelical circles shaped by evangelist Dwight L. Moody (1837–1899), he was alarmed at what he saw as the apostasy and degeneration of modern civilization. The dispensational premillennialism he espoused (see CH #128) expected Christ’s return and the final judgment at any moment.

By the twentieth century, Blanchard often looked for evidence of true Christianity in the things that a believer stood against, including card playing, dancing, theater attendance, smoking, and drinking. He was at the center of the emerging fundamentalist movement, drafting the 1919 doctrinal statement for the World’s Christian Fundamental Association.

After Charles Blanchard died, 31-year-old J. Oliver Buswell (1895–1977) succeeded him. Buswell established central principles that would characterize Wheaton for most of the twentieth century. He valued the intellectual life and took advantage of Wheaton’s strongest academic asset: its heritage as a classic liberal arts college. While preserving strict fundamentalist restrictions, he also saw to it that the school was accredited, with academic programs and requirements much like more secular peers.

Buswell was also a Presbyterian of the strictest sort. After famous scholar J. Gresham Machen (1881–1937) led a conservative revolt against mainline Presbyterians, Buswell followed suit in 1936. But Buswell, premillennialist and ardently anti-alcohol, went further. When Machen died in 1937, Buswell joined Carl McIntire (1906–2002; see CH #138) to form the strictly fundamentalist Bible Presbyterian Church. Wheaton trustees, fearing that Buswell was drawing the school too much into the separatist Presbyterian movement and alienating other fundamentalists, terminated his presidency in 1940.

New evangelicals

Buswell’s replacement, V. Raymond Edman (1900–1967), was almost the polar opposite. The child of Swedish immigrants, he had served as a missionary to Ecuador and a Christian and Missionary Alliance pastor. Neither Reformed nor intellectual, he welcomed a wide range of fundamentalist traditions and helped build Wheaton’s image. At the same time, he showed little concern for strengthening the college’s intellectual mission.

Buswell and Edman exemplify Wheaton’s tensions between piety and intellect. Piety was vastly the more popular emphasis, but the school always had a much smaller side that valued intellectual rigor. The story of the Wheaton philosophy program illustrates this.

In 1936 Buswell hired fellow separatist Presbyterian and follower of Machen, Gordon H. Clark (1902–1985), a rigorous young philosopher. Clark helped inspire intellectual revival, one part of a 1940s and 1950s “new evangelical” renewal.

Among his students were Carl F. H. Henry (who later founded Christianity Today), Baptist theologian Edward J. Carnell, Paul Jewett (later a Fuller professor), Harold Lindsell (one of Fuller’s founders and author of The Battle for the Bible), and Orthodox Presbyterian theologian Edmund Clowney. Even Billy Graham took a course with Clark. Clark also frequently bred controversy, a trait that led to his forced resignation in 1943. The college then placed philosophy under the Bible Department. Carl Henry later lamented the replacement of required courses on ethics and theism with those on scriptural memorization and soul winning.

In 1950 Wheaton hired Arthur Holmes (1924–2011), a British émigré who had just earned a Wheaton BA in Bible, to teach philosophy. Holmes, who eventually earned his PhD, was an inspiring teacher and soon restored philosophy’s popularity at Wheaton. Nonetheless, not until 1967, after a painful struggle and a threat to resign, did he succeed in getting philosophy reestablished as a separate department.

Meanwhile, many on the faculty were quietly resisting the strictest fundamentalist teachings. English professor Clyde Kilby (1902–1986), for instance, celebrated C. S. Lewis as the era’s leading traditional Christian apologist. Lewis smoked, drank, and rejected fundamentalist essentials, such as biblical inerrancy and young-earth creationism. Nonetheless, Kilby made Wheaton a center for Lewis studies, founding the Wade Center to promote Lewis scholarship.

Wheaton scientists, however, did not receive the same indulgence. Russell Mixter (1906–2007), a zoologist, cautiously advocated a very conservative version of theistic evolution he called “progressive creationism.” That was too much for yet another major force in Wheaton’s history—the trustees. In 1961 they added an addendum to the doctrinal standards stating that Adam and Eve were “created by a direct act of God and not from previously existing forms of life.”

All truth is God’s truth

During the 1960s, guided by faculty members, an impressive number of students were also engaging with promising intellectual trends in the broader evangelical world. In 1955 Holmes started an annual Wheaton Philosophy Conference (an early precursor of the Society of Christian Philosophers) that brought interaction with Calvin College’s inspiring philosopher, William Harry Jellema (1893–1982), and his protégés, Alvin Plantinga (b. 1932) and Nicholas Wolterstorff (b. 1932), founders of a new school of thought known as Reformed epistemology. Holmes became a leading promoter of this outlook in readable books: All Truth Is God’s Truth (1977), Contours of a World View (1983), and Fact, Value and God (1997). He also trained over a hundred students who went on to earn doctorates, train their own students, and further develop distinctly Christian philosophical outlooks that earned respect even in the academic mainstream.

Philosophy provided an important foundation for a new outlook emphasizing “the integration of faith and learning,” which began spreading throughout the network of evangelical schools of which Wheaton was the leading model. Soon it wasn’t just philosophers; every major discipline had a society of Christian (meaning evangelical) adherents. In 1976, 38 evangelical colleges founded the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU, now with over 180 member institutions).

Despite its role near the center of this rebirth, Wheaton’s balancing act continued, as exemplified by Noll’s famous book. Rigorous college education had been spreading for decades in evangelical circles, and students from evangelical schools were crowding into respected graduate programs. CCCU schools could choose among excellent faculty candidates and were no longer the poor relations in American higher education. In Jesus Christ and the Life of the Mind (2011), Noll documented hopeful evidences of academic recovery. But he also observed that tensions between scholarship and conservative Christian anti-intellectualism remained strong.

In 1945 famed theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971) had written, “Culturally obscurantist versions of the Protestant faith are so irrelevant to religion in higher education that no policy in the academic program can hope to overcome the irrelevance.” At that time Wheaton was the leading fundamentalist college. By the twenty-first century, evangelical academia had achieved a degree of cultural relevance Niebuhr had thought impossible. Yet it was still struggling to negotiate tensions between populist piety and dedication to careful intellectual inquiry as one essential dimension of the larger evangelical enterprise. CH

By George M. Marsden

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #139 in 2021]

George M. Marsden is professor emeritus at the University of Notre Dame and author of Fundamentalism and American Culture, Jonathan Edwards: A Life, and The Outrageous Idea of Christian Scholarship. This article is adapted from The Soul of the American University Revisited: From Protestant to Postsecular.Next articles

Seeking and teaching virtue

Christian bearers of the liberal arts tradition from the Middle Ages to the present

Jennifer A. BoardmanHumility, truth, mentoring, love

Is something missing from the modern university?

the editors and interviewees