A Christian revolutionary?

IN THE EARLY to mid-twentieth century, the world was in crisis. The consequences of World War I had been economically disastrous. Politically the unsatisfactory peace settlement in 1919 led to the emergence of totalitarian regimes in Italy, Spain, and Germany, led by men whose names have echoed through the decades: Franco, Mussolini, Hitler. By 1939 the arrival of new conflict was hardly a surprise.

Meanwhile the church in Western Europe stood firmly on the defensive. Although several revival movements had brought new enthusiasm, in general Christianity felt its influence over mainstream intellectual life, government, and the arts slipping away. C. S. Lewis summed up the dominant religious belief of the time as being not genuine Christianity, but “a vague theism with a strong and virile ethical code.”

This lack of influence was partly the church’s own fault. Christianity and the arts often seemed at odds. W. E. Yeats, born in 1865, noted that when he was young, “there were as many religious poets as love poets,” but that by the turn of the century, poets were no longer interested in religion. Lord David Cecil (Oxford professor and a member of the Inklings), when trying to find poems for The Oxford Book of Christian Verse, concluded that Christians were no longer writing poetry. You wouldn’t find them in the theater either, especially since it had been illegal in Britian since the early seventeenth century to represent any of the three persons of the Trinity on stage. The bishop of Oxford in the late nineteenth century forbade all priests in his diocese, including Dorothy L. Sayers’s father, Henry, to attend theatrical performances. (Lewis Carroll, a colleague of Henry’s, resisted becoming a priest for this very reason.)

Many believers thought, as Sayers explained in 1941, that “the Church of Christ should live within the world as a self-contained community . . . offering neither particular approval of, nor opposition to, those departments of human activity . . . summed up in the words ‘civilisation’ and ‘the state.’” Christians who were both in the world and of it had, she said, become “involved in the state machinery,” identifying themselves with fallible and sinful regimes and coming under the same judgment. Both of these were defensive postures. Sayers was ready to go on the offensive.

Detecting Christ

William Temple, future archbishop of Canterbury, and George Bell, bishop of Chichester, played their parts in this midcentury recovery of Christian relevance, but lay Christian writers involved in the fallen world on a daily basis proved even more capable of thinking outside the ecclesiastical box. Perhaps the most surprising of these was Sayers, the daughter of a clergyman and a writer of best-selling detective novels.

Not only was she the only high-profile woman in a church completely dominated by men, but she was also eccentric, was married to a divorced man, and had borne a child out of wedlock. Yet she played a leading role in the renewal of Christian drama and applied her knowledge of the Bible and the creeds to the problems of her generation. In so doing she proclaimed a genuine Christian approach to art and voiced a powerful theology of work.

When Sayers was a child, the discovery that Cyrus the Persian and King Ahasuerus could be found both in her history books and in the Old Testament convinced her that “history was all of a piece and the Bible was part of it.” During the economic and political crises of the late 1930s, according to her biographer Barbara Reynolds, Sayers “experienced a return of the vision she had had as a child, of the relatedness and wholeness of things. . . . Her mind focused on the central belief of Christianity—the Incarnation—and she saw how all else flowed from it.” In fact, three principal doctrines of Christianity—Creation, Incarnation, and the Trinity—came together in her mind to throw light on her world and the problems of her age.

Sayers had not published anything with a religious theme since some early poems, but was recommended by Charles Williams to the organizers of the Canterbury Festival as a potential author for their 1937 festival play (see “So great a cloud of witnesses,” pp. 26–27). She accepted the commission, as well as the suggestion to write about William of Sens, an architect who rebuilt the choir section of Canterbury Cathedral after a twelfth-century fire.

The play, The Zeal of Thy House, continued Sayers’s reflections on vocation and professional integrity from her novel Gaudy Night (1935), but in a specifically Christian context. At its end Archangel Michael invites the audience to praise God the Creator, declaring that every work made by human creation is “threefold, an earthly trinity to match the heavenly.” The “Creative Idea” existed from the beginning in the maker’s mind; the “Creative Energy,” through work, enabled the idea to become incarnate in the material world; and the “Creative Power” transformed and inspired those who encountered the work.

This ambitious theme launched Sayers into the world of theology. Articles on Christian doctrine she wrote for the Sunday Times as publicity for the play attracted the attention of church leaders. For the next few years, Sayers’s work took her in three directions: presenting the Incarnation of Christ to the general public through drama; exploring a Christian understanding of the arts; and applying Christian doctrines to economic and employment issues, advancing a specifically Christian view of society.

Putting Jesus on stage

Although the Canterbury play succeeded with critics and the public, the ban on putting God on the stage forced the divine element to be portrayed by four huge angels. Sayers was unhappy, feeling that “the device of indicating Christ’s presence by a ‘voice off’, or by a shaft of light, or a shadow . . . tends to suggest to people that he was never a real person at all.”

Radio broadcasts were exempt from the regulations governing the stage, and in 1938 Sayers was given the opportunity to write a nativity play for the BBC. He That Should Come included the sound of the baby Jesus crying and struck people by its realism. As a result the BBC asked Sayers for a series of 12 plays on the life of Christ. She agreed on the condition that she could use contemporary language and that Jesus would be played realistically by an actor.

No actor had played the role of Christ in Britain for nearly 400 years, and people only knew his words in the archaic English of the King James Bible. But in spite of vigorous opposition, the plays became an overwhelming success. The BBC’s director of religious broadcasting admitted they “revealed the poverty and incompleteness of [his] own belief in the Incarnation.” Many others credited Sayers with helping them believe for the first time that the Gospel stories really happened.

Sayers also sought to explain the reasons why the church and the arts were at odds. She wrote that the church had “no Christian philosophy of the Arts” and no coherent attitude toward art: it “puritanically denounced the Arts as irreligious and mischievous” or tried to manipulate them as a means of propaganda, but never approached them theologically.

Sayers set a new course in her most original book, The Mind of the Maker, where art is seen as a form of creation by humans created in the image of the Creator God, exploring her trinitarian analogy of the nature of artistic creation (Idea, Energy, and Power). The work of art, like the Holy Spirit, goes out into the world with the power to inspire and transform.

She applied this understanding of humanity’s God-given creativity not only to the arts but also to all secular work, saying, “man is most godlike and most himself when he is occupied in creation,” and, “every man should do the work for which he is fitted by nature” to find satisfaction in the work done and not just work because he needs money to live.

Talking about a revolution

The church tended to imply that clergy and other religious workers had a vocation while everyone else just “worked.” Sayers recognized and preached that humans could be called to serve God in their secular work. In December 1940 the leaders of the British churches included in a set of “ten points for peace” the idea that “the sense of Divine vocation must be restored to man’s daily work.” This emphasis came explicitly from the 1937 Oxford World Conference on Life and Work, but it was Sayers, not official clergymen, whom churches often called upon to explain this point.

Yet Sayers was of the opinion that this change in attitude to work would be difficult in the economic system as it was. She thought both capitalism and socialism to be profoundly flawed, allowing the nature and needs of human beings to be submitted to financial considerations. She suggested changes she called “so revolutionary . . . as to make all political revolutions look like conformity” and “a radical change from top to bottom—a new system; not a mere adjustment of the old system to favour a different set of people.”

In this system the quality and usefulness of what is made would be more important than whether it makes a profit. The nature of the work done and its suitability for each worker’s talents would take precedence over time-saving and salary levels. The Christian economist would act believing that if we seek first the Kingdom of God and his righteousness, all other things will be added unto us (Matt. 6:33), and the church would no longer have to struggle to persuade the working person to “remain interested in a religion which seems to have no concern with nine-tenths of his life.”

Whether in art, politics, or economics, Sayers’s principle remained the same: “not to try and shut out the Lord Immanuel from any sphere of truth or activity.” If we truly believe in him, she wrote, then whether we are involved in scientific research, or the arts, or medicine, or industrial manufacturing, “Christ is precisely the truth we are discovering, the beauty we are expressing, the life we are restoring,” and the source of all the “energy and skill we put into these things.”

Today she would be glad to see that God may now appear on the British stage and that Christian drama is no longer considered shocking. At the same time, she would be sad but not surprised to find that attitudes toward vocation have not greatly changed since her day. She would, if she were with us, find work at hand yet to do. CH

By Suzanne Bray

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Suzanne Bray is professor of English at Université Catholique de Lille; the author of numerous books and articles on Sayers, Lewis, and Williams; and the editor of translations of Sayers’s works into French.Next articles

“We still make by the law in which we were made”

Tolkien and “subcreation” — the making of a secondary, fictional world

Colin DuriezFriends, warriors, sages

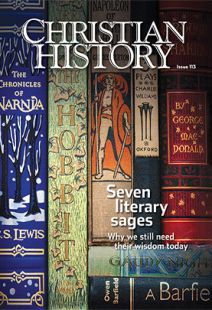

How seven writers gave us stories that endure, imparting truths that never fade

the editors with Alister McGrath, Chrystal Downing, Colin Duriez