A city on a hill?

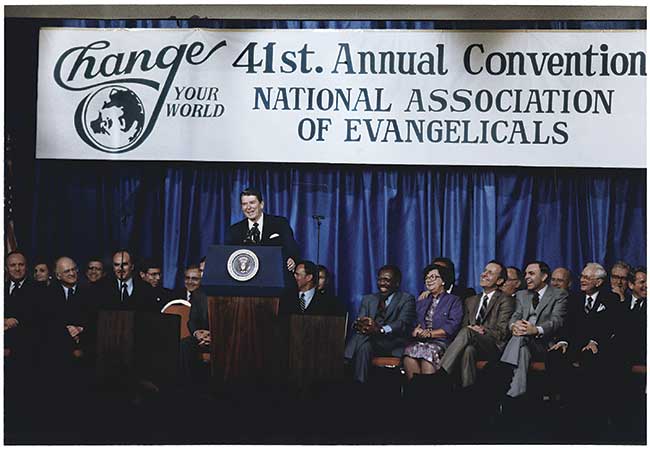

[President Reagan addressing the Annual Convention of the National Association of Evangelicals. 1983. National Archives / Courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidential Library]

In January 1983, near the tail end of the worst recession since World War II, President Ronald Reagan (1911–2004) addressed an annual convention of national religious broadcasters. The theme was “facing the future with the Bible,” and Reagan announced that as president he would do his part. “At the National Prayer Breakfast,” he said, “I will sign a proclamation making 1983 the Year of the Bible.”

Knowing that some might criticize him for failing to separate church and state, Reagan declared that he was doing nothing less than the founding fathers of the nation who had supposedly looked to the Bible for guidance. In invoking these foundations, Reagan articulated a theology in which God specially chose and set apart the United States with a unique role in human history:

I’ve always believed that this blessed land was set apart in a special way, that some divine plan placed this great continent here between the two oceans to be found by people from every corner of the Earth—people who had a special love for freedom and the courage to uproot themselves, leave their homeland and friends. . . . They created something new in all the history of mankind—a country where man is not beholden to government, government is beholden to man.

A special role

Reagan was clearly not alone. According to recent polling from the Public Religion Research Institute, 40 percent of Americans believe God has granted the United States a special role in human history. In addition 36 percent say the United States has always been and is currently a Christian nation.

Usually Americans bolster such a belief by turning first and foremost to the Pilgrims (as Reagan often did). Where others came for gold, the story goes, these settlers came for God. They left England for the freedom to practice what they believed and established a colony bent on returning to the old truths of the Bible. In time the burgeoning of this Bible-based New England led to the flourishing of the United States. The Mayflower Compact became the US Constitution. Though no religion was officially established, the nation was Christian at its core.

How much of this is true?

Consider for a moment the chief sermon used to support this story: John Winthrop’s 1630 “city on a hill” address, “A Model of Christian Charity.” John Winthrop (1588–1649) was the first Puritan governor of Massachusetts Bay; he represented the Puritan movement, which arrived a decade after the Pilgrims but shared many of their same Protestant convictions.

On the voyage from England to Massachusetts, he declared, “we shall be as a city upon a hill.” According to the usual story, that idea structured the settlement of the Puritans, whose descendants spread it beyond New England. In the 1830s the visiting French writer Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859)—whose Democracy in America (1835) remains influential—claimed:

The foundation of New England was a novel spectacle and all the circumstances attending it were singular and original. . . . The civilization of New England has been like a beacon lit upon a hill, which, after it has diffused its warmth around, tinges the distant horizon with its glow.

This idea percolated for years, and in the twentieth century, Reagan used Winthrop’s sermon to cement the notion that the United States had been set apart from its very “first” moment to be a “shining city on a hill.”

Sermon on a hill

The actual history behind these tales has often been lost (sometimes intentionally, sometimes not). Winthrop’s “city on a hill” sermon, for example, was almost completely unknown in its own day. No Puritan talked about it, Winthrop never mentioned it, and the text of it was never published. We don’t know when, where, or even if Winthrop ever delivered it. Only one copy of the sermon survives, and it isn’t in Winthrop’s handwriting. It was discovered in 1838 and first published by the Massachusetts Historical Society, where it again languished unknown in a giant tome of documents.

Only in the context of the Cold War did this sermon begin to emerge as central to the story of America. At that point a Harvard professor named Perry Miller (1905–1963) argued for the sermon’s foundational significance, and Harvard graduate John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) became the first president to use Winthrop’s “city on a hill” sermon, in his farewell address to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in January 1961.

Soon Winthrop’s sermon started appearing in history textbooks and literary anthologies. More politicians cited it. Another Harvard scholar, Sacvan Bercovitch (1933–2014), claimed in the 1970s that this single sermon served as the beginning of all things American. By the time Reagan anchored his own political rhetoric in Winthrop’s sermon, American culture had adopted this Puritan text as foundational. But this was very much a Cold War creation. All the way up through World War II, the phrase “city on a hill” had retained its biblical basis in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:14)—referring almost exclusively to the church, not the nation.

Law from the Good Book

Whether they paid attention to Winthrop or not, it is indeed true that the Puritans hoped to remove ceremonies and inventions from the church and return it to the pure, primitive simplicity they found in the Bible. They hoped to model simplicty to others and further the cause of the Reformation. To achieve this they turned to the Bible in conjunction with classical and Enlightenment models, separating government from church while also insisting that government’s role was to nurture and support true religion.

Their initial law codes, as a result, frequently cited biblical injunctions. Sometimes this meant greater lenience (theft was punishable by death in England but not in New England); and sometimes it meant greater severity (adultery was punishable by death in New England, but not England—though Puritans enforced this only once). New England in the seventeenth century had become a “Bible commonwealth,” though one mightily infused with English cultural ideas that could often be mistaken for biblical norms.

But the Pilgrims were not the first people here (these were the Native Americans, of course), nor the first Europeans (Spanish, French, and Dutch came earlier), nor the first English voyagers, nor even makers of the first permanent English settlement (Jamestown, 1607). When they were set forth, often intentionally, as the true origin of America, all these other beginnings and their influences were erased.

When history textbooks in the early nineteenth century began to tell the nation’s history for future generations, such messy details were often glossed over or omitted. Textbook authors, largely New Englanders, took the opportunity to cast their ancestors with noble hearts and motives. The South was mostly ignored to downplay slavery and elevate a commitment to noble ideals. The Puritans were also largely wiped clean of slavery. But, in fact, they had participated in the slave trade and had enslaved Native Americans and Africans.

Furthermore the Pilgrims and Puritans had considered economic opportunity to be just as vital and important a reason for immigrating to New England as religious purity. They took their place among many groups mingling the devout and the profane, including people committed to the Bible, people who ignored it, people who used the Bible for unjust gain, and people who never could tell the difference.

The biblicism the Puritans brought to bear on society did not entirely disappear, though. This meant a high rate of biblical literacy on the one hand and an attempt to support any and all policies with scriptural texts on the other. The Bible was prevalent in the Revolutionary era, though not necessarily among founders themselves. Biblical texts do not appear in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, or any new state charters. Religion was not really part of the rationale for a new nation or the structure it would take.

Instead the Bible surfaced most readily in the sermons of ministers who used Scripture to sanctify the nation and present it as essentially, if not officially, Christian (see pp. 12–15). Some preachers launched jeremiads against the Revolution, and Loyalist ministers rejected it altogether, but many supported it. It was preachers, not politicians, who truly created the idea of a providentially elected people and set them apart with a special mission—a nation taking over the role of the church, fulfilling the truths of Scripture, even when God’s will and ways, as then understood, mixed cultural norms and secular ideas with biblical texts. Ministers made sacred the work of politicians.

A new Israel?

A huge number of preachers (especially from New England) repeatedly turned to the story of Israel’s exodus to make sense of American destiny and justify the United States’ departure from England. In this context the idea of America as a “New Israel” took shape. The Revolutionary era cast this idea back to the Puritans, and many still believe that it arose primarily from them, but the Puritans had always considered themselves to be part of a worldwide church, turning to the story of Israel as a biblical model and paradigm for any group of gathered Christians.

But for Americans in the new nation a century after the Puritans, the story of Israel was not just a model or a paradigm, but prophecy. Increasingly American ministers argued that their new nation was now taking the mantle of the covenant to advance the Kingdom of God. Ezra Stiles (1727–1795), a leading New England theologian and the president of Yale College, represented the rhetoric of many with his 1783 sermon, “The United States Elevated to Glory and Honour.” Using Deuteronomy 26:19, Stiles turned to the subject of “God’s American Israel” and concluded that this verse is “allusively prophetic of the future prosperity and splendor of the United States.”

In many ways these ministers simply reapplied what had become standard practice throughout the eighteenth century. Protestantism had come to play a powerful role defining what it meant to be British and why the British Empire must succeed. Biblical interpreters had already begun to argue that God works his will primarily through the power of the state and the moral expansion of nations.

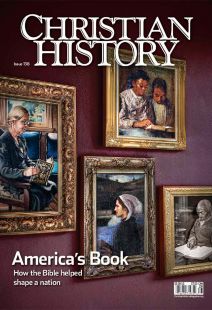

To understand why these interpretations would have such staying power, we have to look beyond the founding to the early decades of the new nation. It was then, not during the actual founding, that the Bible truly began to exert profound and pervasive cultural influence (see pp. 19–21) as a burst of revivals brought it into newfound prominence. In 1816 the American Bible Society (ABS) began a massive production and distribution of Bibles (see pp. 29–31).

Just one of many such institutions, the ABS became part of a larger cultural explosion of biblicism in the early to mid-nineteenth century. Historian Paul Gutjahr reminds us that the Bible was “the most imported, most printed, most distributed, and most read written text in North America up through the nineteenth century.”

It is no accident that the burst of history textbooks in the 1820s—written in part to give the relatively young nation a history to bind its citizens together—largely took a providential tone. In schoolbooks throughout the country, God foresaw and created the United States as a crowning glory in the history of redemption.

All this provided a moment when the American Revolution was recast as a New Israel escaping the tyranny of Britain as a modern-day Egypt. Another such powerful moment arrived in the Cold War, when church membership again rose exponentially. In the face of an explicitly atheist and communist foe, the nation defined itself as always essentially religious and capitalist. In 1954 the United States added “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. And soon Perry Miller, then JFK, and eventually Ronald Reagan all turned to Winthrop’s forgotten sermon and pronounced it the origin of the country.

Who is Egypt?

From the moment of the Revolution forward, whether consciously or subconsciously, the nation has attempted to take on a prophetic role, acting as a deliberate agent in God’s redemptive history of the world. While that story has been perhaps the most powerful or noticeable, it is by no means the only story. If minorities, particularly African Americans, had been afforded the opportunity to write the nation’s biblical history, the story would look very different (see pp. 24–28).

People of color in the United States have read the Bible against, rather than with, the broader American culture in which they were embedded. Providence does not point to the making of the United States, they argue; providence points beyond it. Far from being a New Israel, America is a new oppressive Egypt, which needs to be transcended. The Bible offers deliverance, promises, and hope, not past achievement or present identity. Condemnation, not sanctification, marks the prophetic tone ringing from its pages.

In the Revolutionary era, though, the nation’s founders had pulled from a large mix of resources to establish the contours of a new country. They utilized new Enlightenment philosophies and political theories, combining them with a careful searching of classical sources. As these ideas took shape in Revolutionary America, biblical rhetoric soon came along to bless and sanctify them. To this day we live with the consequences of that act—a nation that all too often perceives itself as a church. CH

By Abram Van Engen

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #138 in 2021]

Abram Van Engen is associate professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis and the author of Sympathetic Puritans: Calvinist Fellow-Feeling in Early America and City on a Hill: A History of American Exceptionalism.Next articles

Preaching the holy war (Bible in America)

Both sides in the civil war appealed to the Bible

James H. Moorhead