“A new Pentecost”

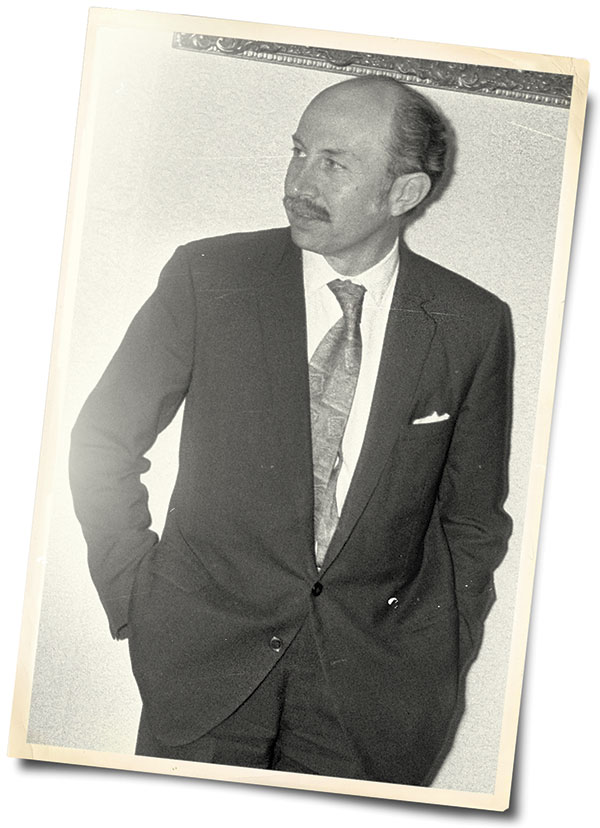

[José Míguez Bonino, liberation theologian, 1974 / Wikimedia]

IN 1968 the Council of Latin American Catholic Bishops (CELAM) held a conference in Medellín, Colombia, with Pope Paul VI in attendance. The event has been celebrated—and condemned—as a fountainhead of liberation theology. Recalling his experience Bishop Marcos McGrath (1924–2000) said: “We left Medellín inspired as by a new Pentecost.”

Not just business as usual

Over half a millennium, councils of the Catholic Church in Latin America mainly disseminated the teachings of European councils. While a few Latin American bishops attended the Council of Trent (1545–1563), it was overall a council of Europeans and for Europeans. The Council of Lima (1582–1583) and the Council of Mexico City (1585) then brought Trent’s version of ecclesial reform in the wake of the Protestant Reformation to Latin America.

Likewise though 53 Spanish-speaking bishops and 7 Portuguese-speaking bishops attended when Pope Pius IX (1792–1878) convened the First Vatican Council (1869–1870) to address European crises arising from the European Enlightenment, the end result was a Latin American church that looked more like Rome, not the other way around.

Three decades later Pope Leo XIII (1810–1903) saw a need to consolidate the Latin American churches, fragmented from independence movements (see “Strangers in a strange land,” pp. 29–33). Nearly half of the Latin American bishops attended his Latin American Plenary Council in Rome in 1899. A series of Eucharistic congresses followed, culminating in Pope Pius XII (1876–1958) approving the formation of CELAM. It first met in Rio de Janeiro in 1955; when a second conference convened in Medellín in 1968, people expected that it would proceed with business as usual, adopting policies put forth in the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). The moment however was ripe for change.

Even after their official political independence, Latin American nations had retained economic dependence first on Great Britain and then the United States. The year 1959 proved to be a watershed moment; the Cuban revolution had shown the possibility of a Latin America free from economic and political dependence on the United States. The Kennedy administration responded by propping up Puerto Rico as a model of liberal democracy and capitalist investment.

Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress offered similar benefits to all Latin America, hoping to prevent further leftist and communist revolutions, but lack of adequate funding and internal inefficiencies doomed it to failure. Hyperinflation, social unrest, and political instability spiked in the 1960s. Alliances between Latin American economic elites and the United States unleashed right-wing coups all over Latin America. The masses were caught in the crosshairs.

The surprise of Medellín

At Medellín the bishops committed themselves to ecclesial engagement in the social changes already underway. They decided first, to champion in Latin America the human values of justice, peace, education, and the family; second, to evangelize through catechesis and the liturgy; and third, to adapt the structures of the church to new Latin social realities. One report recorded an emotional call for a church of the poor:

A deafening cry pours from the throats of millions of men, asking their pastors for liberation that reaches them from nowhere else. . . . The Latin American bishops cannot remain indifferent in the face of the tremendous social injustices existent in Latin America. . . . Christ, our Savior, not only loved the poor, but rather being rich He became poor. He lived in poverty. His mission centered on advising the poor of their liberation and He founded His Church as the sign of that poverty among men.

The bishops exhorted Catholics to respond by evangelizing the poor, seeking solidarity with the poor, and becoming poor. While Medellín did promote Vatican II’s teachings, participants also spoke of something new, reminiscent of Pentecost; the Holy Spirit was using the Latin American church to impact the universal church. This emerging “liberation theology,” focused on freedom for the oppressed, was the surprise of Medellín.

What did liberation theology look like? First, it identified the church as being united in solidarity with the poor; second, it committed to work for the liberation of the poor; and third, it preached true communion among all children of God, not just the hierarchy. Medellín encouraged the already emerging movement of base ecclesial communities—groups gathering to worship and discuss the Bible in solidarity with each other rather than in submission to the church hierarchy. It also promoted other parachurch groups committed to the transformation of Latin American society.

The Second Vatican Council had invited Protestant observers to attend; the only Latin American Protestant who came was Argentinian Methodist José Míguez Bonino (1924–2012). He later wrote, “For the first time in the history of Christianity a Council is convened with the specific purpose of opening lines of communication, rather than building trenches and walls for the protection of the Christian faith.”

At Medellín Pope Paul VI invited Míguez Bonino once more. Deeply moved by the council’s call for Protestants too to end their “social strike” and engage the realities of the Latin American context, Míguez Bonino affirmed the questions posed: How does the church catholic serve the peoples of Latin America? How is ecumenism a liberating movement in the continent? What is Jesus Christ’s vocation and mission here and now? These questions would prove to be divisive.

But Medellín did not initially trouble the sleep of US Protestants. Dow Kirkpatrick, pastor of Atlanta’s St. Mark United Methodist Church, wrote 10 years later, “Most of us were unaware of [Medellín] when it was happening. The publication in English of Gustavo Gutiérrez’s A Theology of Liberation (1973) led to the discovery that five years earlier a major watershed in modern church history had occurred.” Gutiérrez (b. 1928), a theologian and Dominican priest, had spoken at conferences on these issues and consulted at Medellín.

The fact that most North Americans first heard of Medellín from Catholic sources such as Gutiérrez led to a mistaken belief that Latin American Protestants were idle bystanders in this movement. But Protestant theologians like Míguez Bonino actively participated in Catholic movements, and the term “liberation theology” itself appears to have been coined by Brazilian Presbyterian Rubem Alves (1933–2014). Currents running through Medellín converged with similar streams in Latin American Protestantism in the work of theologians like Julio de Santa Ana (b. 1934) and Emilio Castro (1927–2013).

Medellín among the evangelicals

Like their Catholic counterparts, Latin American Protestants had been overlooked by the 1910 Edinburgh World Missionary Conference. In 1949 the first Latin American Evangelical Conference (CELA I) defined Protestantism in Latin America as a single “evangelical” movement embracing all non-Catholic Christians. But when CELA II met in Peru in 1961, seams in its unity were already beginning to show.

One sticking point was evangelical engagement with ecumenism. The word itself sounded too close to “communism” and evoked specters of a modernist, liberal Christianity ill-fitted for the realities of Latin America. The formation of Church and Society in Latin America (ISAL) with the support of the World Council of Churches in 1961 brought even greater consternation; ISAL applied the “Theology of Revolution” of Presbyterian theologian Richard Shaull (1919–2002) and Marxist analysis to the Latin American struggle.

These theological currents had caused anxiety among North American Christians long before Medellín. They tarred CELA II in Peru in 1961 as procommunist—one result was the brief arrest of some of the conference’s key leaders, like Míguez Bonino. By the time CELA III met in Buenos Aires in 1969, a few months after Medellín, opposition was fully mobilized.

The Evangelical Committee on Latin America (ECLA), an evangelical missions organization that had formed in 1959, boycotted CELA III and staged the first “Congress for Latin American Evangelization” (CLADE) in the same year. Míguez Bonino spoke at CELA III and was invited to attend CLADE I—for what many hoped would be an encore of his CELA III address—but he was not allowed to speak because organizers perceived his thought as too close to European theologians like Barth, Brunner, and Bultmann.

Yet at Medellín after many years and against all expectations, seeds of the gospel sown in soil bloodied by the swords of conquistadors, the bullets of narcos, and the money of multinational corporations yielded fruit. The bishops proclaimed that we are called to be one so that the world—particularly the poor and marginalized—may believe that the Father has sent the Son, who became poor so as to make many rich. That idea continues to challenge the global church. And the question of whether liberation theology represented a compromise with political movements to achieve that goal, or truly was a new Pentecost, has not died away. CH

By Edgardo Colón-Emeric

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #130 in 2019]

Edgardo Colón-Emeric is Irene and William McCutchen Associate Professor of Reconciliation and Theology at Duke Divinity School, director of the Center for Reconciliation, and senior strategist for the Hispanic House of Studies. He is an ordained United Methodist minister.Next articles

Pope Francis (b. 1936)

In 2013 Francis became the first pope from Latin America

Jennifer Woodruff TaitRooted and released

Diversity and complexity mark today’s Latin American church

the editors with Justo L. González and Ondina E. GonzálezLatin America: Recommended resources

Here are recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors that begin to explore the complex subject of Latin American Christianity.

the editors