A substantial work

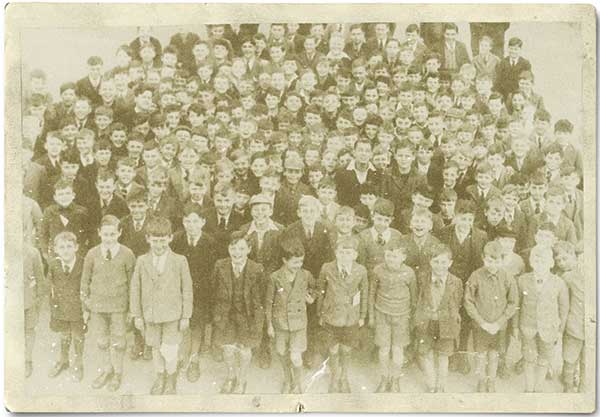

[Ashley Down orphan boys in 1935]

BY 1870 George Müller was overseeing five large orphan houses in the Ashley Down area of Bristol. Together these buildings could accommodate 2,050 orphans and the 112 staff members needed to care for them. Unusual for the time—and in opposition to the harsh treatment that occurred in workhouses—these orphans were not only fed and clothed, but also took part in religious instruction, exercises, and games, and were educated up to the age of 14.

At this stage boys usually left to start a trade apprenticeship with employers who had applied for an apprentice from the homes. The girls tended to stay in the orphan homes until 17 or 18, helping out with the daily housekeeping work while training for domestic service, in which many of them would find gainful employment.

Müller prayed with each orphan before he or she left, and every child, except those few who returned to their extended families, went off to work. They departed with a tin trunk containing two changes of clothes, an umbrella, a Bible, and a copy of Müller’s biography. The homes paid both their train fare and the boys’ apprenticeship fees.

This amazing ministry had grown from humble beginnings. Müller’s life was a living example of the verse he much prized from Psalm 81:10: “Open thy mouth wide, and I will fill it.”

Looking back Müller reflected how God drew him to certain key people and places at just the right time so that the Lord’s work could be accomplished. His troubled young life is well known (see “Delighted in God,” pp. 6–12); yet even as a new believer, the Lord brought him into contact with three influential people who put their Christian calling before all else. In these encounters the seeds of Müller’s work were sown.

a trio of good examples

The first of these influencers was Hermann Ball, described by Müller as “a learned man, and of wealthy parents,” who had turned his back on worldly riches to work as a missionary among the Jews in Poland. Müller met him in 1826 shortly after his conversion. At that time Müller had given up the Lord’s work for a youthful romance; he was afraid that the parents of the girl he was interested in would not let her marry a missionary. But Ball’s example inspired him to seek the Lord whole-heartedly and to put nothing before his place of primacy. Müller ended the romance, and it is likely that Ball’s desire not to be conformed to the expectations of his class, education, and privileged background also inspired the young Müller to a similar resolve.

This resolve was certainly tested when Müller’s father made known his displeasure at his son’s hopes of becoming a missionary:

My father was greatly displeased and particularly reproached me, saying that he had expended so much money on my education, in hope that he might comfortably spend his last days with me in a parsonage, and that he now saw all these prospects come to nothing. He was angry, and told me he would no longer consider me as his son. But the Lord gave me grace to remain steadfast.

That steadfastness to God’s call was a constant thread through Müller’s life.

A second lasting influence on Müller’s orphan work was Pietist author A. H. Francke (1663–1727), professor of theology at Halle University from 1691 to 1727. Not content to merely teach theology, Francke felt a desire to show God’s faithfulness to his contemporaries. Street children in Wittenberg caught his attention, and in 1695 he decided to open a “ragged school” for them in a single room.

Within three years Francke was overseeing two educational orphan-houses (later known as the Franckesche Stiftungen), caring for 100 orphans and educating another 500 day-pupils on religious subjects. Francke’s initiatives so impacted his colleagues that, by the time Müller began studies at Halle University in 1826, the institution provided free lodgings to young scholars like Müller. Francke’s example of social care and trust in God for his needs lay in the soil of Müller’s heart for the next six or seven years, before finally sprouting in Bristol.

The third influential figure was the man who became Müller’s brother-in-law: Anthony Norris Groves. Müller first heard about this dentist-turned-missionary soon after his arrival in London in March 1829. He noted that Groves had felt called by the Lord to resign from his lucrative profession (and salary of £1,500 a year), seek only the Lord for his material needs, and take his wife and children to Persia to spread the gospel.

Müller recorded: “This made such an impression on me, and delighted me so, that I not only marked it down in my journal, but also wrote about it to my German friends.”

“Bristol is my place for a while”

The inspiration provided by these three formative influencers—keeping God as the highest priority; social concern, especially for poor children; and trusting solely in the Lord’s provision—had a lasting effect on Müller. He withdrew from the relative security of the London Missionary Society in early 1830, and in October 1830 he married Anthony’s sister, Mary Groves.

The new couple soon resolved to refrain from receiving a salary, doubtless inspired yet again by Mary’s brother. Müller kept this practice throughout his life, and it was a well-established habit by the time he moved to Bristol in 1832. After a visit there in April, he recorded, “I feel that Bristol is

my place for a while.” So it was to be; he arrived in May 1832, and it became his home base for the rest of his life.

In Bristol Francke’s influence on Müller emerged again. Cholera was rife in the United Kingdom, having arrived from the Baltic in December 1831. It had spread quickly, and by July 1832 the first cases of cholera in Bristol came to Müller’s attention. The epidemic raged all summer, only abating in October; nationwide it claimed 55,000 lives. In February 1833 Müller read about the life of Francke, including Francke’s orphanage work, and took inspiration to increase his reliance on God to help the less fortunate:

The Lord graciously help me to follow him [Francke], as far as he followed Christ. The greater part of the Lord’s people whom we know in Bristol are poor, and if the Lord were to give us grace to live more as this dear man of God did, we might draw much more than we have as yet out of our Heavenly Father’s bank, for our poor brethren and sisters.

stirred into action

On June 12, 1833, Müller felt stirred to provide education to those poor to whom he had previously given charitable assistance; this also followed Francke’s example, and in March 1834 the work was begun. In November that year at a fellow believer’s house, he saw a copy of Francke’s biography on the shelf. Once again he recorded: “I have frequently, for a long time, thought of labouring in a similar way, though it might be on a much smaller scale.” The following day he decided to stop thinking about this wish and start acting upon it.

Obviously there was a clear physical need, but that was not Müller’s primary reason for establishing the orphan work. His Narratives record his main aim as being to strengthen his fellow Christians’ faith. He cited different examples of believers who, in his view, would benefit from such a witness.

There were those whose lack of trust in the Lord’s provision compelled them to labor long hours to make ends meet; those concerned about avoiding the poor-house in old age; businessmen who adopted worldly standards in their trade to succeed instead of trusting in God’s provision; and those whose jobs forced them to compromise with the world but who were fearful of voicing their disapproval. To all these—and more—he wished to testify to God’s faithfulness and trustworthiness, just as Francke’s work had done to him:

I remembered what a great blessing my own soul had received through the Lord’s dealings with His servant A. H. Francke, who, in dependence upon the living God alone, established an immense Orphan-House, which I had seen many times with my own eyes.

Müller’s meticulous bookkeeping and recording of donations given in answers to prayer would also parallel Francke’s narration.

On December 5, 1835, during his daily Bible reading, Müller was struck by Psalm 81:10. He began to pray for £1,000 and premises and staff to establish an orphan house; five days later he issued a press statement detailing his plans. Five months later, he issued a second press statement, this time to announce the opening of the first orphan house at 6 Wilson Street, Bristol, for destitute girls and his plan to open a second. On November 28, 1836, this second one (at 1 Wilson Street) was opened, and by April 1837 each house accommodated 30 children, probably with four or five children to a room. The following year 3 Wilson Street was opened for orphaned boys, followed in July 1843 by 4 Wilson Street for older orphan girls.

Accommodating so many children in terraced properties (Americans call them “row houses”) on a residential street was not without problems, however. On October 30, 1845, Müller received “a polite and friendly letter” from a neighbor, explaining how the noise of the orphan houses inconvenienced some of the other properties. Earlier Müller had rejected thoughts of building a permanent establishment, but this letter provoked a reconsideration.

After prayer and reflection, Müller started praying for £10,000 (about $1.2 million) to construct an orphanage. By February 1846 he had found land that the owner offered to him far below its market value. Although there continued to be regular tests of his determination to trust God for all the means for the work (see “Even the wind obeyed,” pp. 18–20), he was well on his way. The “New Orphan House” at Ashley Down opened in 1849 and was followed by subsequent houses in 1857, 1862, 1868, and 1870.

the funeral that stopped a city

England’s famed author Charles Dickens, in the 1857 collected volume of his weekly magazine Household Words, wrote in uncharacteristically understated tones that Müller “has accomplished in his own way a substantial work that must secure for him the respect of all good men, whatever may be the form of their religious faith.”

George Müller spent many of his last years traveling in evangelistic work through the United States, India, Australia, China, and Japan before retiring home to Bristol in 1892. By that time the orphanage spread over 19 acres in five large houses at Ashley Down and involved thousands of pounds in supplies and many daily donations. Müller recorded in 1895 that the year’s donations had included:

9,455 quarterns [3.5 pound loaves] of bread . . . 141 lbs of butter, 13 very large cheeses . . . 59 lbs of tea, 239 lbs of bacon . . . 72,648 apples, 7,037 pears, 240 lbs of cherries, 3,362 plums, 4,174 buns, 22 cases of oranges, a large quantity of potatoes, carrots, turnips, flour. [He added:] There were also two living oxen sent to be killed for meat.

Müller’s funeral brought Bristol to a halt. Factories and businesses closed across the city, and thousands of people came out to mourn and pay their respects as the funeral procession passed by. The Bristol Times remarked that “he was raised up for the purpose of showing that the age of miracles is not past.” C H

By Philip Thomas

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #128 in 2018]

Philip Thomas is training coordinator and lecturer in theology at Müllers, based in Bristol.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: From orphans to martyrs

The influence of Müller, his friends, and his movement was long-lasting

the editors