Caught up to meet Jesus in the clouds

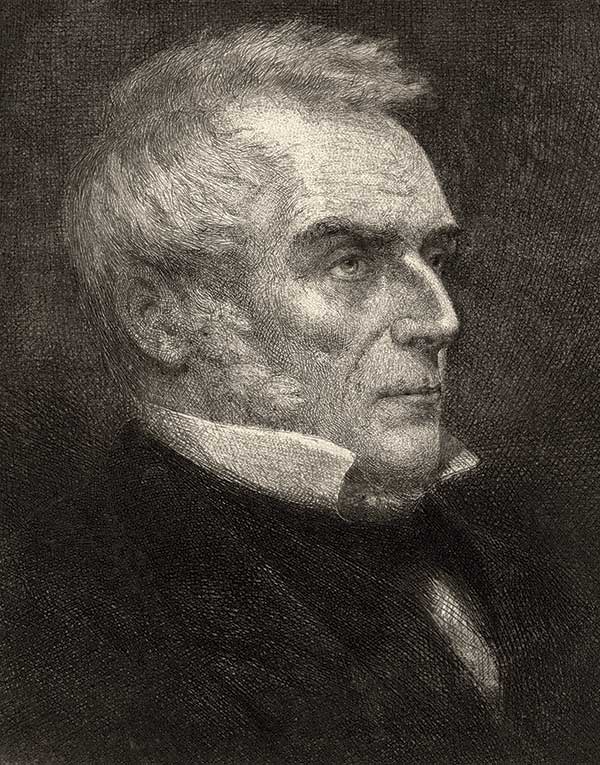

[John Nelson Darby]

FROM LEFT BEHIND to numerology, the picture of the “last things” painted by many Christians today looks different than it did before the middle of the nineteenth century. Up to that point, most American evangelicals imagined that the church was the New Israel, heir to the promises of the Old and New Testaments. It would persevere through tribulation to triumph and enter the blessed millennium of Revelation 20. Only then would Christ return to bring about the consummation of all things. That view, known as postmillennialism, formed a near consensus.

Beginning in the 1830s, a new paradigm, in which Christ would rapture believers before a great tribulation that would precede the millennium, began to displace the old. By the early twentieth century, this view, known as premillennialism, had come to predominate. Its chief architect: John Nelson Darby.

called to god, not the bar

The youngest son of a wealthy Anglo-Irish merchant, Darby was born in London in 1800 into a world of commerce and privilege. All was not ideal—he had a distant father and an absent mother—but he showed resourcefulness and talent, graduating in 1819 from Trinity College, Dublin, as its top-ranked classics student. A promising career in law awaited him, but by then his religious turn was already underway.

This was not entirely surprising—Trinity College was a stronghold of Anglican Evangelicalism. Though called to the bar as a lawyer in 1822, Darby forsook that profession to enter the Anglican ministry. After his 1826 ordination in the Church of Ireland, he took charge of a destitute parish in rural County Wicklow, about 15 miles south of Dublin. His parishioners knew him as a tireless, compassionate, and intensely earnest priest.

He was a priest troubled in spirit, though, as his developing views of true Christianity increasingly clashed with the Anglican establishment. A turning point came in 1827, when a serious injury forced him into extended convalescence. He spent months of recuperation pondering his vexed questions. Soon a set of core convictions emerged. One was radical biblicism—truth found in Scripture alone, interpreted literally in its plain meaning. Another touched on ecclesiology: he saw the church as a spiritual priesthood of believers. And finally Darby found certain assurance of Christ’s Second Coming followed by a millennial reign on earth.

Over the next few years, the young minister grew further estranged from Anglicanism. Meanwhile he began to affiliate with likeminded people dismayed by Christian division and unbiblical traditions. They longed for the purity, simplicity, and unity they saw in the New Testament and called themselves “Brethren”—and, like Darby, they were making their way out of the established church.

By turns personable and persuasive, disheveled and difficult, Darby was a force of nature; he soon dominated the young movement through will and strength of intellect. One could find his imprint virtually everywhere, but especially in the Brethren’s understanding of the end of time. Europe in the early nineteenth century—wracked by political, economic, and social revolution—formed a cauldron of prophetic speculation. Darby interacted with millenarian views of Edward Irving (1792–1834), a Presbyterian who ended up founding his own movement, as well as Jesuits and Jansenists (the last was a Catholic movement emphasizing human depravity and divine sovereignty).

Darby’s system turned on a sharp distinction between Israel and the church. “Rightly dividing the word of truth” (2 Tim. 2:15) meant recognizing their distinct roles and correctly discerning the dealings of God with each. Israel is an earthly entity, the recipient of temporal promises literally fulfilled on earth. The church is a heavenly entity, the recipient of spiritual promises fulfilled in the heavenlies.

With that principle of interpretation in place, the divine narrative came more clearly into view, though still not as clearly as Darby’s readers might have wished: he wrote voluminously and imaginatively but not lucidly. His mature scheme, though, generally identified six “dispensations.”

The first began with Adam and extended to the great flood. The second stretched from Noah to Abraham. The Abrahamic dispensation continued until the giving of the law to Moses. The fourth dispensation—the dispensation of Israel—was the most complex and crucial. Not only did it contain three subdispensations (law, priesthood, and kingship), it also featured an innovation that, for Darby, unlocked the secrets of the last days. He felt Israel’s rejection of the Messiah had interrupted the fourth dispensation after week 69 of the 70 weeks prophesied in Daniel 9:24. The result was a fifth dispensation, a vast parenthesis within the fourth, unrevealed to Old Testament prophets and governed by God’s dealings with the church.

the interrupted story

Living Christians, then, found themselves in the Gentile dispensation, the Church Age, but how might they expect it to end? Here Darby introduced another distinctive feature: 1 Thessalonians 4:17, where the saints are caught up to meet the Lord in the air, pointed to a future rapture that would remove the church and end the Gentile dispensation. Christ would return and take Christians to their reward, resuming the interrupted dispensation of Israel before a period of intense “tribulation”—Daniel’s 70th week.

And what a week: the great tribulation, the rise of the Antichrist, Armageddon, and the triumphant return of Christ in the long-awaited Second Coming. Afterward, with Satan bound and the Antichrist defeated, the millennium—Darby’s sixth dispensation—would begin, the final stage in God’s dealings with his earthly people, Israel. Raptured Christians, meanwhile, would enjoy eternal bliss in heaven. Finally, at the end of the millennium, all believers would be united in the new heaven and the new earth of Revelation 21.

For those who followed this logic and verified the scriptural coordinates on which it rested, this argument held great coherence, explanatory power, and persuasive force—and it placed Darby’s readers into a gripping narrative with the whole of history in its view.

only a spiritual church

Darby grounded his beliefs about the church in his beliefs about the end times. Like other primitivists he sought to follow the apostolic church. Yet he also adamantly opposed any attempt to restore apostolic glory. Every dispensation was destined to end in failure; the present was no exception. The visible church lay in ruins, an apostate Christendom. The true church, spiritual and invisible, without creed or clergy, persisted only as a faithful remnant. God’s plan for the church now was rapture, not restoration.

Darby remained an influential figure, but controversy dogged his later decades. In the 1840s a series of disputes escalated into a full-scale schism that split the movement, with Darby at the head of the smaller Exclusive Brethren wing. He grew estranged from many of the movement’s cofounders and came under attack from junior associates and younger Open Brethren, who held him responsible for dividing the movement. Yet he persevered, itinerating into his eighties. His health failed him in 1881, first through a fall and then a stroke. He rapidly declined and breathed his last on April 29, 1882.

Though indefatigable and overpowering, Darby was ill-equipped to popularize his own system. Spreading dispensational premillennialism to the masses depended on more pragmatic spirits. By the late 1870s, it had begun to prevail in prophecy conferences and camp meetings across North America, with dynamic champions like Dwight L. Moody (1837–1899), A. J. Gordon (1836–1895), and A. B. Simpson (1843–1919).

It swept the holiness movement and was carried forward into Pentecostalism. In the mid-twentieth century, it was broadcast by radio evangelists like Charles Fuller (1887–1968) and propagated by fundamentalist institutions. Along the way it was adapted, systematized, and refined into a seven-dispensation system by scholars like Cyrus Scofield (1843–1921)—whose Scofield Bible was its greatest single aid—and Charles C. Ryrie (1925–2016), who also produced a popular study Bible.

We are approaching 200 years since Darby first began to formulate his ideas, but his influence has not abated. Whenever American evangelicals today ponder the state of the Late, Great Planet Earth, or shudder in fear of being Left Behind, they reveal the extent to which they are living in the world Darby fashioned. CH

By Roger Robins

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #128 in 2018]

Roger Robins is a professor in the Center for Global Communication Strategies at the University of Tokyo.Next articles

A Christian organization with integrity

Today the work that Müller began is carried on in a different form. CH managing editor Jennifer Woodruff Tait had the opportunity to visit in Bristol with Phil Thomas, training coordinator and lecturer in theology at Müllers, the charity that continues George Müller’s work.

The editor and Phil ThomasGeorge Müller: Recommended resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you better understand Müller and the Brethren.

the editorsModern Amnesia, Did you know?

Modern thinkers who have turned to the early church weren’t the first to do so.

the editors