Reformation to the present 1500–2000, Part 2

[pages 86—87]

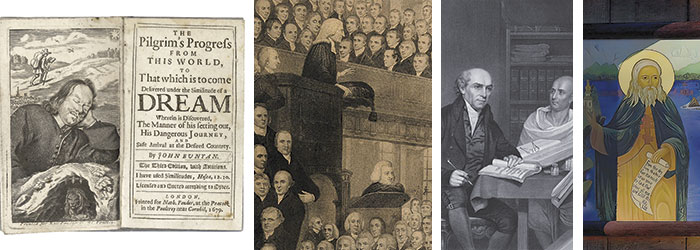

With the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, Puritans such as John Bunyan were imprisoned for pastoring outside the Church of England. His 1678 allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress ( left, first edition with illustration of author) is arguably the first English novel; written behind bars, it became a popular and influential Christian work. Named for the Wesley brothers’ orderly regimen of Bible studies, worship, and charity work, the Methodist revival sought to re-infuse Anglican practice with genuine experiences of God’s love. John and Charles Wesley‘s experiences of God’s love in 1738 shaped the content of John’s preaching and also the over 6,500 hymns (1739 hymnal not shown) Charles wrote. (The Wesleys are in the upper and lower pulpit center left, 1822 engraving.) Meeting resistance from the Anglican church and responding to ministry opportunities in the newly independent United States, the Methodists became a church in their own right around the same time as William Carey (center right, 1813 engraving) was founding the English Baptist Missionary Society in 1792. Carey was a powerful evangelist and linguist in Calcutta, India, who translated the Bible into several Indian languages. Herman of Alaska (right, Spruce Island icon) also journeyed east with the gospel, arriving at the Aleutian Islands in 1794. Working against the injustices of imperial Russian traders, he fought fiercely for the equality of the Aleut people, called the colonists to repentance, and established a lasting Orthodox Church in Alaska that remains vibrant.

[pages 88—89]

While missions have remained a consistent priority of the church from the apostles onward, increasing global connectedness in the 19th century created new opportunities for many Christians swept up in fresh evangelical fervor. The London Missionary Society’s ship, the Duff (left, c. 1820), embarked in 1796 on a voyage to bring “the glorious gospel of the blessed God” to the South Pacific. Many missionaries also took up the cause of the enslaved around the world as cultural debates over the ethics of slavery reached a fever pitch. In Britain the abolition movement garnered support from influential figures like ceramicist Josiah Wedgewood, whose Antislavery Medallion (second from left, 1787) became a powerful symbol of the struggle for freedom. In the United States in 1816, Richard Allen (center) was ordained bishop in the new African Methodist Episcopal Church, which ministered to enslaved and free Blacks and published the first African American newspaper. Fueled by his own evangelical Christianity, William Wilberforce (second from right, 1794 portrait) led a conflicted English Parliament to abolish slavery in 1833 with his passionate rhetoric and uncompromising persistence. The same year John Keble (right) and John Henry Newman published Tracts for the Times. Concerned that the Church of England’s practice was becoming merely cultural and that the state too closely controlled it, the “Tractarians” sparked the Oxford Movement, which worked to connect Christians to the historic, universal church. Keble edited collections of early church writings, encouraged clergy to prioritize pastoral ministry, and restored traditional liturgies to worship.

[pages 90—91]

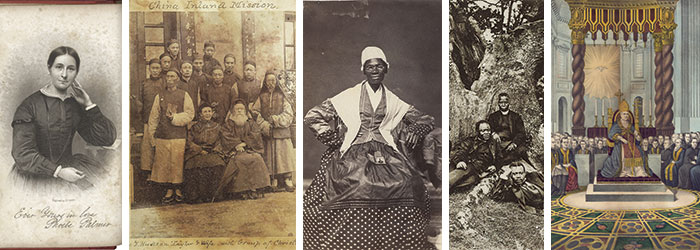

The Holiness movement grew out of Methodist revival activities such as the inspirational prayer meetings of Phoebe Worrall Palmer (left, 1845). Her books, such as The Way of Holiness, called believers to encounter and experience the transforming Spirit of God. After his own conversion, Hudson Taylor (bearded in second image from left, with wife Jennie and converts) studied medicine, surgery, and midwifery, learned the Chinese language and customs, and smuggled himself through guarded ports to evangelize thousands. In 1865 he founded the China Inland Mission. As Taylor battled the destructive opium trade in China, vocal street evangelist Isabella Van Wagener believed she had received a divine order to travel the United States preaching God’s goodness and mercy. Renaming herself Sojourner Truth (center, 1863), she gave impassioned biblical exhortations for the abolition of American slavery, an abolition not fully enacted until 1865. In 1864 Samuel Crowther was ordained bishop of Niger at Canterbury. The Church of England’s first bishop of Nigerian heritage, he is pictured upright against a tree (second image from right) in 1873 with other Anglican leaders. Amid growing social and political unrest in Europe, Pope Pius IX convened the First Vatican Council (right, 1870), hoping to unify Catholicism against secularism and materialism; the arrival of an occupying army in Rome cut it short.

[pages 92—93]

As the gospel swept rapidly through Buganda, a Bantu kingdom in Uganda, the kingdom’s young kabaka (king), Mwanga, saw Christianity as a threat to his tyrannous rule. Starting in 1885 he systematically martyred 45 Catholic and Anglican missionaries and converts, known as the Uganda Martyrs (left, wood relief from Catholic shrine in Kampala). Amy Carmichael (not shown on this web page, early 20th c.) transformed the lives of young women in India, rescuing many from temple prostitution through the Dohnavur Fellowship. She evangelized in India for 55 years and carried the 19th century’s energy around global missions into the 20th. In 1904 the Welsh Revival, emphasizing the Holy Spirit’s transformative power, renewed the faith of hundreds through prayer, confession, and jubilant singing among the region’s many coal miners. Some worship services took place in the dangerous mines themselves (center right, acrylic on paper, 1910s). These stirrings in Wales inspired other movements around the world, including India, where Pandita Ramabai (center left) led the 1905 Mukti Revival, and California, where the Azusa Street Revival initiated by William Seymour’s Apostolic Faith Gospel Mission (right) launched the now massive Pentecostal movement in 1906.

[pages 94—95]

The World Missionary Conference (left, 1910, Edinburgh) saw unprecedented evangelistic unity among Protestants and created a global mission and ecumenical network. Yet the 20th century proved to be bloody and tumultuous—two world wars, the Holocaust, Nazi and Soviet regimes, and the threat of nuclear warfare. Witnessing to these realities, Exodus, by Jewish painter Marc Chagall (right, 1952), depicts the crucified Christ participating in the sufferings of people in all ages. The last century marked 2,000 years since our Lord’s death, but 2,000 years since his Resurrection, too, and modern Christians throughout the world continued to shine light in the darkness. The Second Vatican Council (not shown on this web page, 1962), continued the work of the first, considering how to minister more effectively to modern Catholics. Evangelist Billy Graham converted thousands; Martin Luther King Jr. preached and lived out daring biblical appeals for racial justice in the United States (center left); Mother Teresa healed and dignified the most destitute untouchables of India; and Polish philosopher Karol Wojtyla, who became Pope John Paul II, championed Christian anthropology and helped to end the Cold War (pictured together center right).

The story of Christian history continues, and, just as Christian history began with Christ’s coming, it will someday end with Christ’s coming again. Because Jesus of Nazareth walked on Earth, Christians trust that his passion conquered all the darkness of the human story; all light is a glimpse of his restoration, and all who believe in him will rise in his abundant life on the Last Day.

By Max Pointner

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #144 in 2022]

Max Pointner, issue writer and image researcher at CH, has an undergraduate degree in art history from Wheaton. He teaches history, literature, and Latin at Charis Classical Academy in Madison, Wisconsin, and directs the Charis theater program.Next articles

Christian history in images: recommended resources

Some resources to help you put this issue in context

the authors and editorsFavorite Christian History issues

We asked past and current team members of CH and other friends of the magazine to share their favorite issues with us and, if they wished, to tell us why.

friends and team members of Christian History magazineErasmus: Did you know?

What Erasmus thought about preaching, proverbs, shopping, and Martin Luther

the editors