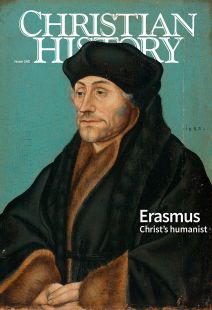

Spiritual father or rejected scholar?

[Anabaptists attempting to hide in a forest. Bullinger, Heinrich; Thomann, Heinrich: [Kopienband zur zürcherischen Kirchen-und Reformationsgeschichte]. [Zürich], 1605–1606. Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Ms B 316, f. 142v and 245v. https://doi.org/10.7891/e-manuscripta-18901 / Public Domain, Mark]

John Choler, a friend of Erasmus from Augsburg, told him in 1534 that Martin Luther had called Erasmus a “double-tongued impostor, a satanic schemer . . . an Anabaptist, a Sacramentarian, an Arian, a Donatist, a triply-great heretic and a crafty mocker of Christ, and six hundred others of this kind.” While in some writings Erasmus had occasionally praised Anabaptist religious devotion, he also realized that being accused of Anabaptist sympathies was dangerous. He rejected any connection to the quickly stigmatized and criminalized reform movement. In a 1534 letter to Guido Morillon, he wrote:

The Anabaptists have flooded the Low Countries just as the frogs and locusts flooded Egypt: a mad generation, doomed to die. They slipped in under the appearance of piety, but their end will be public robbery. . . . Although they teach absurdities, not to say impossibilities, and although they spread unlovely things, the populace is attracted as if by a fateful mood or rather the impulse of an evil spirit in this sect.

Yet in the preface to his 1524 Paraphrases, Erasmus had stated that it made sense to baptize young people again after they had been instructed in the faith; in Complaint of Peace (1517), he had written critically about warfare; and he criticized excesses of the clergy and lack of authentic faith within the Catholic Church—as did the Anabaptists. His contemporaries—and critics—noticed. Such accusations tied Erasmus to the Anabaptist movement, no matter how much he protested. But how much of Erasmus’s work preceded Anabaptist ideas? Was he really their spiritual father?

A third way

Anabaptists came into the public eye in late January 1525 with their first baptism in Zurich. Some believers from the circle of reformer Ulrich Zwingli had already expressed reservations about infant baptism and about Zwingli’s views on the close connection between faith and political authorities (see pp. 20–21). The Anabaptists formed a third way or third wing of the Reformation—identifying as neither Catholic nor Protestant. Other baptisms followed; the new movement quickly gained adherents.

The Anabaptists’ teachings challenged centuries-old premises of Christian life in the Holy Roman Empire. They rejected military service and oath swearing, they refused to submit to territorial churches, and they practiced communal Bible study with interpretation by the community of believers rather than the clergy. Secular and ecclesiastical authorities fought them from the beginning through persecution, forced migration, imprisonment, and the death penalty. Despite these hardships they survived; today the Mennonites, the Hutterites, various Brethren groups, and the Amish trace their roots back to them.

The question of the relationship between Erasmus and the Anabaptists, however, revolves around defining humanism. Did humanism only unite those, like Erasmus and Thomas More (see p. 32), well versed in ancient languages and literature and sharing a common ethic? Or was humanism a broader community in which any intellectuals who saw themselves as avant-garde could come together through letter-writing friendships, discourse, and debate? Was this a community into which Anabaptists could have made inroads?

Such intellectual Christian communities were forming all over Europe, including in Zurich, where humanistic reading circles gathered around Zwingli and interacted with his ideas. These were comparable to the Sodalitäten—circles in university towns in which a scholar gathered students around him. Beginning in 1520 the group included Conrad Grebel (c. 1498–1526), Felix Mantz (c. 1498–1527), and Simon Stumpf (dates unknown).

These men were part of a humanistically educated middle (burgher) class—a class that often served as the driving force for religious renewal in cities. They endeavored to provide “religious food” for themselves through small gatherings, thus remedying a shortfall they blamed on the Catholic Church. The means for hiring Reformation-minded preachers came from burgher-funded foundations.

Thus the men around Zwingli, who later became Anabaptist leaders, met to discuss theological issues and to read the Bible together. In doing so they gradually developed explicit disagreement with Zwingli’s aims.

Important Anabaptist preachers of the first generation, such as Grebel, Mantz, and Balthasar Hubmaier (1480–1528), also had humanist university educations and exchanged letters in educated circles. Hans Denck (c. 1495–1527) and Ludwig Hätzer (1500–1529) were versed in ancient languages, as evidenced by their German translation of the Old Testament’s prophetic books (1527).

Baptism and oath-swearing

Erasmus’s influence can also be seen in the work of Menno Simons (1496–1561), who referenced Erasmus’s writings in his own work. He cited the humanist’s critical inquiry into infant baptism as an apostolic institution and referred to Erasmus’s remark (in his New Testament edition) that Jesus had forbidden swearing oaths. Historians assume that Menno at least possessed Erasmus’s Latin translation of the New Testament; whether he also owned Erasmus’s Paraphrases is not certain.

Some scholars argue that Menno not only knew Erasmus’s theological works well, but that key statements of his theology can be traced back to Erasmus. Menno’s knowledge of Latin, his ability to participate in intellectual discussions, and some of his theological wording, terminology, and arguments indicate that he was educated in humanistic thought and influenced by Erasmus in particular. Three aspects of his theology seem particularly Erasmian—his emphasis on the way of salvation, his basic thoughts about the material-spiritual contrast, and his criticism of the medieval church as being the religion of the material.

The Hutterites, an Anabaptist community that led a well-organized and prosperous life while holding goods in community on their farms in Moravia, also read the works of famous humanists. The tolerant environment of Moravia enabled the Hutterites to write extensively. The works of Erasmus circulated in their community, and Hutterite preachers used them for exegesis and to prepare their own spiritual writings. Some biblical paraphrases handed down by the Hutterites seem to show Erasmus’s influence. These may go back to early leader and elder Peter Riedemann (c. 1506–1556), author of the Hutterites’ basic “Account of Our Faith.”

But looking at Anabaptists outside these leaders, as well as at developing Anabaptist communities that promoted the priesthood of all believers, provides a different answer. Here a clear bias prevailed against university education and humanistic ideas. A famous Anabaptist saying ran: Die Gelehrten, die Verkehrten (The learned, the incorrect).

Discipleship and peace

Later historians have never come to a consensus. Ludwig Keller (1849–1915) in The Reformation and the Older Reform Parties (1885) saw the Anabaptists in the tradition of the Waldenses, the Bohemian Brethren, and Erasmus—focused on discipleship, turning away from the world, and peace. Walther Köhler (1870–1946), a church historian in Zurich, also argued that Erasmus was the “spiritual father of the Anabaptists.” In contrast influential North American Mennonite theologian and historian Harold Bender (1897–1962) was critical of the thesis that Erasmus and humanism significantly influenced the Anabaptists. Bender believed that Zurich leaders such as Grebel, Mantz, and Sturm had turned away from humanism to give priority to the restoration of the early church.

Ultimately those who see Erasmus as an intellectual, deeply steeped in learned languages and connected to networks of scholars, will emphasize the contrast with the Anabaptists. Whoever classifies him as a biblical humanist writing against medieval scholastic theology and ecclesiastical corruption will find in him connections to the Anabaptists—no matter how much he may have compared them to frogs and locusts in his own day. CH

By Astrid von Schlachta

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #145 in 2022]

Astrid von Schlachta is director of the Mennonite Research Center in Weierhof, Germany, and lecturer in early modern history at the Universities of Hamburg and Regensburg. She is the author or editor of numerous German-language books on early Anabaptist history.Next articles

Colleagues and critics

Erasmus and his complex relationships with his contemporaries

Jennifer A. Boardman“Wherever truth can be found”

Ronald K. Rittgers and the editorsErasmus: Recommended resources

Read more about the life of Erasmus and his role in sixteenth-century humanism and reform in these resources recommended by our authors and CH staff.

the authors and editors