Everything old is new again

[above: Guiart des Moulins, Peter the Eater, La Bible historiaux ou les histoires escolastres, 15th C. Mazarine Library, MS 313, f 1r— [CC-BY-NC-ND] ]

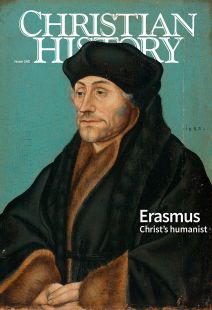

“What is learning, if piety is missing?,” Erasmus asked in a 1529 letter to Juan de Valdes. His concise rhetorical question gets at the heart of Christian humanism—a conscious combination of humanist learning with what Erasmus called the “gospel philosophy,” or “philosophy of Christ.” He thought it obvious that a humanities education provided a necessary foundation for a true understanding of Christianity. He could have easily asked the question the other way around—“What is piety, if learning is missing?”—as he routinely denounced illiterate monks and stupid priests.

Humanism did not always include such an overt concern for religious matters, however. While humanists from Petrarch (1304–1374) on had certainly argued for the compatibility of Christianity and classical culture, the quintessential feature of the movement was an avowed passion for classical, pagan, Greco-Roman antiquity. Many ancient works had been read through the Middle Ages, but some had only circulated in digests and excerpts, and others not at all. Italian scholars—Petrarch, Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459), and their successors—made a concerted effort to scour monastery libraries for less common Latin works. Soon thereafter the West received an influx of manuscripts of ancient Greek texts from the East. Humanists hastened to read, copy, annotate, and translate these works, arguing that they were reviving lost forms of wisdom and eloquence.

Classical conversations

The invention of the printing press in the 1450s and the rapid expansion of the printing industry across Europe in the following decades dramatically hastened the publication and dissemination of books to meet an increasing demand from readers. By the end of the fifteenth century, some printshops specialized in the classics. Venerable scholar-printer Aldus Manutius (1449–1515) in Venice, for example, made works widely available for scholars interested in ancient literature and philosophy and also developed some of the earliest high-quality Greek typefaces for printing ancient works. Now more readers had access, often for the first time, to Latin works—Livy, Quintilian, and Lucretius—and Greek ones—Homer, Euripides, and Plato (or Latin translations of those).

From the late fifteenth century, universities began adding humanities curricula. Students could study poetry, rhetoric, history, grammar (broadly conceived), and philology in Greek, Latin, and, often, Hebrew. Humanists indulged in what we today would call interdisciplinarity: they had wide and varied interests, not all literary. Their revival of ancient works had effects in art and architecture, medicine, and law (see CH #139).

Eventually scholars—even those with no theological training—began to apply the methods of this “new learning” to ancient Christian texts. By the sixteenth century, it was not uncommon to come across someone like Janus of Cornarius (c. 1500–1558), a trained physician with expertise in ancient Greek medicine, translating and publishing ancient medical works by Hippocrates as well as antiheretical works by Epiphanius, the fourth-century Christian bishop of Cyprus.

Typically Christian humanists did not practice these efforts as mere scholarly exercises. They reread texts from the early Christian tradition in an explicit effort to restore that early tradition to a more pristine form and reform the church and European Christian society. What made Erasmus simultaneously immensely popular and so controversial were his assiduous efforts to render Greco-Roman literature, and the new methods developed for studying it, relevant to Christian concerns.

Battle of wits

Humanist engagement with the Bible and doctrine led to an adversarial relationship with professional theologians of the universities, often called scholastics. University theology boasted a rich medieval history; luminaries, such as Peter Lombard (1100–1160), Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), Duns Scotus (c. 1265–1308), and William of Ockham (1285–1347), had advanced the discipline from the eleventh century on. These theologians and their successors often employed a method and style—called dialectic—that humanists argued was overly technical, given to abstract speculation, and stylistically unpleasant. Scholastics argued back that technical philosophical language was necessary for difficult issues; they called humanists mere poets and aesthetes, more concerned with mellifluous language than with truth.

These debates took on a special force in northern Europe. Competing academics vied for positions in university faculties, and professional theologians decried humanist encroachment onto their most coveted territory: the Bible. While the debate encompassed unhealthy and petty squabbles, it was not fought over insubstantial matters. All parties involved thought deeply about the implications of new approaches to sacred texts, as well as the ramifications of examining the Bible in the original Hebrew and Greek when it had been read in Latin for centuries.

Many languages make new ideas

The first forays into such questions, like so much else in the humanist movement, actually started not north of the Alps, but in Italy. Biblical humanism originated with Lorenzo Valla (c. 1406–1457)—a Roman best known for proving that the Donation of Constantine, a purportedly ancient text granting the pope significant temporal power, was a late forgery.

In the middle of the fifteenth century, Valla composed two works comparing the original Greek New Testament with the Latin Vulgate translation. He published neither, but in 1504 Erasmus discovered the second one and published it a year later as Annotationes in Novum Testamentum (Notes on the New Testament). Valla had consulted various Greek manuscripts along with other Latin versions that differed from the Vulgate. In carrying out this comparison for the purpose of establishing a sounder version of the text, he was one of the first European scholars to practice humanist text-criticism of the Bible.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (see p. 36)—a French humanist with a keen interest in ancient Greek philosophy, and a leading figure in Queen Marguerite de Navarre’s reform-minded Circle of Meaux—published two biblical humanist works: first, the Fivefold Psalter (1509), an edition of five different Latin versions of the Psalms; and, second, a new Latin translation of Paul’s epistles (1512), based on the original Greek. Many Christian humanists wanted the Bible in vernacular languages so that all Christians might read or hear it. To this end, Lefèvre also published editions of the Vulgate translated into French.

The Complutensian Polyglot Bible, an extraordinary effort by a group of scholars at the University of Alcalá in Spain, represented another significant achievement of early modern biblical scholarship. Had Erasmus not obtained proprietary rights to publish a Greek New Testament from the emperor and the pope, the Complutensian Polyglot could have been the first Greek New Testament ever published in the modern sense. As it happened it was merely the first ever printed when it came off the press in 1514.

This multivolume Bible contains a Greek New Testament alongside the Latin Vulgate, and also an Old Testament containing the Hebrew original, the Greek Septuagint (an ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew) with an interlinear Latin translation, the Latin Vulgate, an Aramaic (“Chaldean”) version of the Pentateuch, and a Latin rendering of the Aramaic—all on the same page!

But the crowning achievement of biblical humanism, with far and away the most lasting influence, was Erasmus’s 1516 New Testament. Erasmus had several motivations for publishing such a work. He was very interested in technical philological minutiae, establishing the best possible version of the text based on the manuscripts he had at hand—he often claimed, trying to deflect criticism, that he was a mere grammarian. But he also clearly had a higher purpose. In one of several prefatory works to his new New Testament, the Apologia (Defense), Erasmus connected this work with his humanist education:

It is principally for theologians that I have labored over this work of mine, particularly those theologians who either did not have time or did not take the opportunity to study the humanities, without which it is not possible to completely understand divine Scripture.

Erasmus claimed a liberal education to be necessary, not just for translating or critically examining the Bible, but for understanding it. This sly but profound provocation rested at the heart of his vision for a Christian republic of letters—an international intellectual community. In another prefatory work, the Methodus, Erasmus wrote that training only in dialectic and not in the humanities—another jab at university scholastic theologians—results in treating God’s word as “flat,” “frigid,” and “lifeless.”

Erasmus issued nothing short of a call for a revolution in theology as a discipline. In his dedicatory letter to Pope Leo X, appended to the first edition of his New Testament, Erasmus explained his chief hope for the work—“the restoration and rebuilding of the Christian religion.” He believed the New Testament’s truths should be “sought at the fountainhead and drawn from the actual sources rather than from pools and runnels [i.e., possibly corrupt later translations].” Paralleling earlier humanist efforts to restore society by restoring classical literature, Erasmus sought explicitly to do the same for the Christian church by applying humanist methods to the study of the Bible.

To Erasmus’s mind Christianity had suffered a decline not only because it had been coopted by war-mongering princes, lazy monks, and uneducated priests, but because familiarity with the New Testament’s original language and context had been lost. He also thought that the language of the text could be brought up to date with current usage and thus composed paraphrases of most books of the New Testament, creating lively reading for his contemporaries who could read Latin.

These paraphrases were quickly translated into vernacular languages, and for a time every parish church in England possessed the English translation of Erasmus’s Paraphrases (we might compare the modern popularity of The Message). While he continued in the humanist tradition of making available neglected or corrupt ancient classical texts, he also edited and published the works of a dozen early church fathers.

Lost golden age?

Erasmus’s ideal for a golden age of learning and a rebuilding of the Christian religion from its foundations, like everything else in Europe at the time, was severely disrupted by the Protestant Reformation. In the minds of scholastic theologians and conservative Catholic critics, humanism aligned with Luther’s new movement. This claim was not wholly without reason. Virtually all Protestant Bibles printed in any European language during the Reformation era, and for some time afterward, were based on Erasmus’s New Testament.

But simultaneously Protestants distanced themselves from “the old man” when it became clear that he wouldn’t be joining their side. Erasmus himself deeply lamented the fracturing of the church and often expressed a fear of the destruction of the humanities as a result of the Reformation. As for what could be done about any of it, he gave a characteristically learned and pious gloss in a 1521 letter to Pierre Barbier, combining classical and biblical references: “Personally, I see no way out, unless Christ himself, like some god from a machine, gives this lamentable play a happy ending.” CH

By Kirk Essary

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #145 in 2022]

Kirk Essary is senior lecturer in history and classics at the University of Western Australia and director of the ARC Centre for the History of Emotions. He is the author of Erasmus and Calvin on the Foolishness of God.Next articles

Christian History timeline: Erasmus the traveling humanist

Where he went, who his friends were, who argued with him, who read his books

the editors