A diversity of witnesses

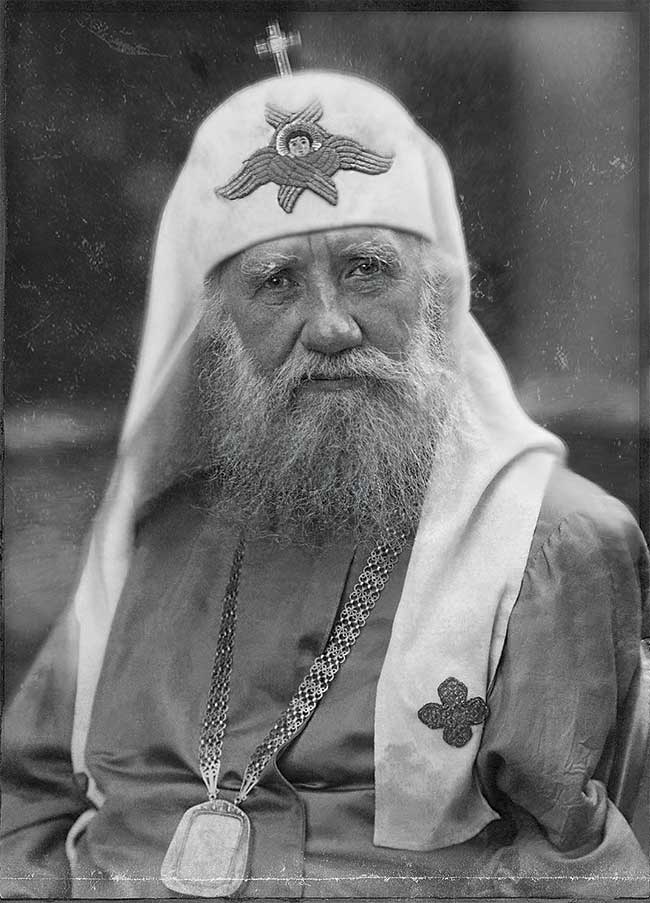

[Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow and All Russia, before 1925—Public domain, Wikimedia]

Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow (1865–1925)

The son of a village priest, Tikhon (Bellavin) went on to study at St. Petersburg Theological Academy. After ordination he was appointed the only Orthodox bishop of North America in 1898. Within the diocese were Russians, Ruthenians, Serbs, Greeks, Syrians, and indigenous Alaskans, and Tikhon worked to make sure all were welcome. He also created the first Orthodox monastery and seminary in the United States, transferred the see to New York from the West Coast, and oversaw the first English-language service book. Tikhon returned to Russia in 1907.

In 1917 the All-Russian Church Council decided that the patriarchate should be reinstated following the Bolshevik Revolution. The council decided to choose the patriarch by casting lots among the three candidates with the highest vote count. Though Tikhon had originally received the fewest votes among the three highest contenders, he was chosen as patriarch by lot on November 5, 1917, the first since Peter the Great abolished the patriarchate in 1721. Tikhon considered his new position a cross to bear instead of a joy to hold.

Patriarch Tikhon soon began condemning the Bolsheviks’ actions against the church. He spoke out against the execution of Tsar Nicholas II, and he reminded the Bolsheviks of their failure to bring the freedoms they promised and the peace they ensured. Tikhon was bold in his assessment of the new regime, and the people listened. The Bolsheviks were listening, too, and did not like what they heard.

Tikhon did not want the church to become a political entity, but he did see his role as being a peacemaker. After the Bolsheviks stole church valuables, prompting Tikhon to advocate for passive resistance, the Bolsheviks arrested the patriarch in May 1922. He was imprisoned for a year, during which time liberal clergy members—Renovationists—declared their loyalty to Soviet rule and defrocked Tikhon.

In 1923 Tikhon was suddenly released from captivity—owing to pressure from the British government—and quickly put forth a neutral position toward the Soviet regime. While some saw his change of tune as cowardice, others saw his greater concern for the ruination of the church in Renovationist hands (see pp. 6–10). As clergy began returning to the patriarch, many left the Renovationist cause, proving both Tikhon’s prominence and acumen. He died less than two years after his release.

Matrona Nikonova (Matrona of Moscow, c. 1880–1952)

Born without eyes in the poor Russian village of Sebino, Matrona Nikonova also lost her ability to walk by her teens. Her brothers became Bolsheviks following the Russian Revolution, so she was forced to leave her family home for Moscow. There she lived under the care of friends and patrons.

In 1993 Zinaida Zhdanova, a woman who used to live in the same house as Nikonova, wrote a book about her former roommate. Zhdanova described Nikonova as a woman familiar with suffering; though born without eyes, Zhdanova wrote, she was able to see the spiritual world with profound clarity. Back in the village, people would visit Nikonova for help with life’s troubles, including illness, relationship struggles, and even spiritual warfare.

On the heels of the immense popularity of Zhdanova’s book, the Russian Church began considering Nikonova for canonization. Controversy ensued around this; theologians Aleksei Osipov and Andrei Kuraev were both openly critical of this move, and Kuraev referred to church officials having thrown her memoirs “into the trashcan.”

One dubious story about Nikonova—in which she assured Stalin that Russia would be able to stand against the Nazis in 1941—gave the church pause, but it was decided to exclude that particular episode from her biography. In recent years, however, Russian nationalists have used that apocryphal episode to help restore Stalin’s image as a hero in defeating the Nazis.

Nikonova was canonized for local veneration in 1999 and for the whole church in 2004. She continues to be a popular saint, especially among Russian women, who value her care and concern for the personal dilemmas of average Russians.

Maria Skobtsova (Maria of Paris, 1891–1945)

Elizaveta Pilenko was born in Riga and raised near the Black Sea. After her father died, she lost her faith, moved to St. Petersburg, and rose in prominence as a poet in the years before the revolution. She married, had a daughter, divorced, and later became the mayor of Anapa for the Socialist Revolutionary Party. During the Russian Civil War, she faced trial for being a Bolshevik sympathizer but was acquitted. She fell in love with Daniel Skobtsov (1884–1969), who was involved in the case against her, and they quickly married and eventually fled to Paris.

When her youngest daughter died of meningitis in 1926, Skobtsova began to turn toward God, embracing a new sense of purpose as a human and as a mother. She aimed “to be a mother for all, for all who need maternal care, assistance, or protection.”

She became a nun in 1932 following her divorce from Skobtsov. Now known as Maria, she devoted herself to serving people in need. She blessed Russian refugees in countless ways: they lived with her in her rented Parisian house, she fed a hundred hungry people each day, she created centers to care for the ill, and she provided spiritual care along with physical attention.

Mother Maria protected Jews during the Nazi occupation of Paris and was allowed to bring food to Jews who were held in a sports stadium before their transfer to Auschwitz. She and her colleague Father Dmitry Klepinin also sheltered Jews who came to their residence, helping some of them escape Paris.

In 1943 Mother Maria, Father Dmitry, and Maria’s son, Yuri, were arrested. Mother Maria was sent to Ravensbrück and, in a rush to execute more prisoners as the Red Army closed in, she was executed just one week before the camp’s liberation in 1945. The ecumenical patriarch canonized Mother Maria, Father Dmitry, and Yuri in 2004.

Anthony Bloom (Anthony of Sourozh, 1914–2003)

Anthony Bloom’s background was diverse. He was born in Switzerland; his uncle was the famed composer Alexander Scriabin, and his father’s ancestors were Scots who had immigrated to Russia. By 1923 the family had made it to Paris to escape the Russian Revolution, and there Bloom began questioning life’s meaning.

He decided to read the Gospels to refute what he believed were false claims. Yet instead Bloom experienced the “vivid sense that Christ was without any doubt standing there . . . if the living Christ is standing here—it means that he is the risen Christ.” Bloom grasped the love of God through Jesus’s presence and work as the suffering savior. After all, he reasoned, Jesus too was once a refugee.

Bloom decided to take monastic orders through the Russian Orthodox Church while simultaneously entering medical school. During World War II, Bloom served as a doctor in the French army and helped the efforts of the French Resistance. Following the war he was ordained as a priest and traveled to England for an Anglican-Orthodox conference. He was later asked to serve at a Russian church in London and was consecrated as bishop in 1957 in a new British diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church called Sourozh.

Through Bloom’s influence as a priest and speaker on British airwaves and television, his church gained both English and Russian converts. Andrew Walker, a British theologian, said that Bloom “indelibly stamped the spirituality and theology of the Orthodox tradition upon the British religious consciousness.”

Because Bloom was an expatriate, he was able to exert pronounced influence over the spirituality of Russians in the Soviet Union—influence that clergy within the country were unsafe to exercise. His Russian sermons were broadcast in the Soviet Union, giving those living under communist rule much-needed spiritual guidance and hope.

Alexander Schmemann (1921–1983)

Born in Tallinn, Estonia, to Russian emigres, Schmemann moved to France as a child, where he became involved in the St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Paris. He grew in faith and knowledge there and later studied at both the University of Paris and St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute. Schmemann married in 1943, had three children, taught history, and moved to the United States in 1951. He began teaching at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in New York during a time when many Russians were immigrating to the United States.

In 1962 Schmemann was elected as dean at St. Vladimir’s, and he also taught at Columbia University, New York University, Union Theological Seminary, and General Theological Seminary in New York, extending his influence much beyond Orthodox circles. He even served as an Orthodox observer to Roman Catholicism’s Second Vatican Council from 1962 to 1965. He became well known as a liturgical theologian and a key figure in Orthodox liturgical renewal.

Schmemann had a great hand in creating the Orthodox Church in America (OCA), which kept expanding to welcome more and more ethnicities within its community, including indigenous Alaskans, Greeks, Bulgarians, Romanians, and Albanians. The Russian Orthodox Church even declared the OCA its own entity (although not all global Orthodox churches agreed). In 1974 the OCA welcomed its first American-born primate, Metropolitan Theodosius.

For 30 years Schmemann’s sermons in Russian were sent over Radio Liberty airwaves to the Soviet Union. The government tried to clamp down on the broadcasts, but Schmemann’s words prevailed to bring hope to those living inside the harsh regime, including famed author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who later became Schmemann’s friend. Schmemann died of cancer in 1983, a man of many worlds but one faithful purpose.

John Meyendorff (1926–1992)

A child of Russian nobility, John Meyendorff was born as an emigre in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. His grandfather was Baron General Feofil Egorovich Meyendorff, an imperial Russian military leader. Meyendorff trained at St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute in Paris and in 1958 earned his doctor of theology degree with a thesis on St. Gregory Palamas, a Byzantine theologian.

The next year Meyendorff and his family moved to the United States, where he began teaching church history and patristics at St. Vladimir’s Seminary in New York. He simultaneously lectured at Harvard University, Fordham University, Columbia University, and Union Theological Seminary.

The greater Orthodox community highly respected Meyendorff’s views, seeing him as a leader and a constant advocate of unity to strengthen the Orthodox Church. Along with Schmemann, Meyendorff helped create the Orthodox Church in America (OCA). Prior to the OCA’s creation, most Orthodox churches in the United States were based on ethnicity. But Meyendorff urged that faith tradition take precedence over ethnic background.

Meyendorff retired as dean of St. Vladimir’s Seminary in June 1992. Within a month of retirement, he passed away of pancreatic cancer at age 66, leaving a legacy of church unity and theological wisdom. His son, Paul Meyendorff (b. 1950), served as the Father Alexander Schmemann Professor of Liturgical Theology at St. Vladimir’s until 2016.

Alexander Men (1935–1990)

Alexander Men was born in Moscow to Jewish parents. His mother, however, was attracted to Christianity, and Men and his mother were both baptized. In 1953 Men had to enter the Institute of Fur instead of Moscow University because of his Jewish heritage. Due to Stalin’s clamp down on Christians as well, Men could not finish his degree in science, instead choosing ordination in 1960.

Serving at a parish outside of Moscow, Men organized a group of priests to stay true to Christian teaching and practice. The group split, however, when member Gleb Yakunin (1934–2014) chose an activist route, bringing international attention to the lack of freedom of religion in the Soviet era. Men chose a different path. Though the KGB constantly surveilled his church, he wished to keep peace with government officials, believing he could have more influence in the culture through goodwill.

Men wrote many books, including The Son of Man (1969), in which he introduced Jesus and the gospel to the modern world with an intellectual and even scientific bent. Men’s influence began to grow when the Soviet Union celebrated the thousandth anniversary of the Kyivan Rus’s conversion to Christianity in 1988. Thanks to the Soviets’ uncharacteristic leniency during the celebration, Men had the opportunity to share his knowledge and experience as a priest in more than 200 speeches over two years.

Still Men spoke out about the dangers of the government ensnaring the Russian Orthodox Church and turning it into an organization more about power and dominance than about changing people’s hearts and minds. On Sunday, September 9, 1990, on his way to the train to take him to his parish, an assassin attacked Men with an ax; Men died shortly afterward. The case has never been solved.

Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow (1929–2008)

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the Russian Orthodox Church suddenly received both the hopeful and monumental task of ushering in a new era of faith unburdened by religious oppression. For almost 70 years, the communist government had suppressed the church at every turn, leaving the clergy split, the Russian people largely unsupported, and generations of people who had never known lives of faith.

Only one year before the fall of the Soviet Union, Alexy II had been elected as new patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church. He was born in Estonia to Orthodox parents and became a Soviet citizen after World War II. He became a priest, then bishop, archbishop, and metropolitan of Tallinn, and also held powerful positions within the Moscow Patriarchate.

Because of these positions, Alexy was able to write a letter to new General Secretary Gorbachev in December 1985. Alexy proposed giving Soviet Christians more influence and freedom, promising the new leader that faithful Christians could help solve some of Soviet society’s problems. Within a year of writing this letter, Alexy was removed from his positions in the Moscow Patriarchate and moved to Leningrad; Gorbachev was not ready to hear what Alexy had to say.

Yet tides changed again in 1990 when Alexy was elected as the new patriarch, in the first free election for the position since 1917. He said, “The church is separate from the state, but it is not separate from society,” and he pushed for chaplains in the military and prisons, religious education in schools, and the reinstatement of church properties. In addition Alexy’s centrist positions between church traditionalists/nationalists and church progressives helped foster a loose unity. A year before his death, the Moscow Patriarchate and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia reconciled. CH

By Jennifer A. Boardman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #146 in 2023]

Jennifer A. Boardman is a freelance writer and editor. She holds a master of theological studies from Bethel Seminary with a concentration in Christian history.Next articles

Questions for reflection: Christ and culture in Russia

Orthodoxy in Russia: past, present, future

the editorsRecommended resources: Christ and culture in Russia

Read more about the complexities of Orthodoxy in Russia in these resources recommended by our authors and CH staff.

the editorsDid you know? Everyday life in the early church

A small taste of what it was like to be part of the early Christian church

the editors and Kate Cooper