One space or many?

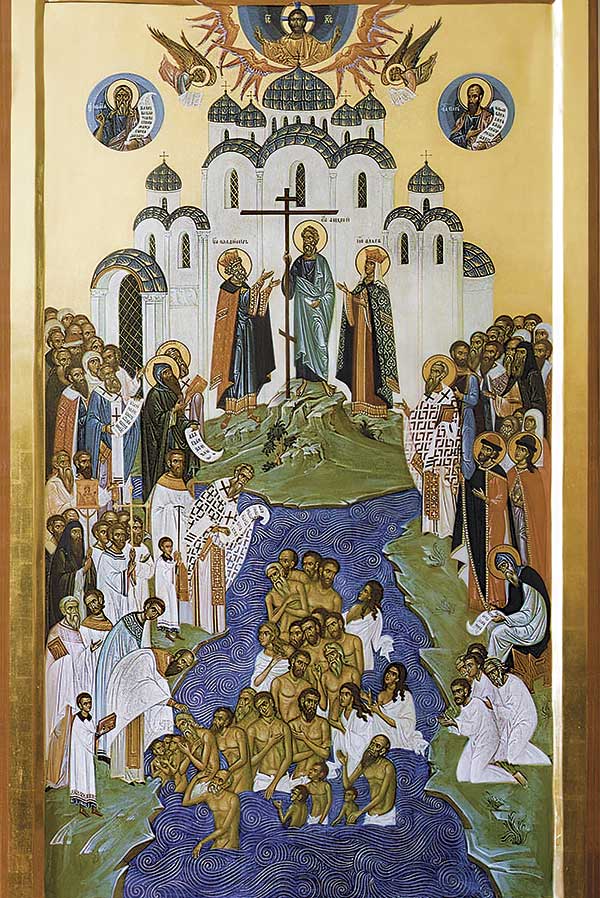

[Above: Reproduction of “The Baptism of Russia” by Father Zenon, 1988. Pskov region, Russia. Photo: Oleg Makarov—Sputnik]

In a sermon given three days after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Patriarch Kirill (Gundaev) of the Russian Orthodox Church called on God to “preserve the Russian land . . . the land which now includes Russia and Ukraine and Belarus. . . . May the Lord protect from fratricidal battle the peoples comprising the one space of the Russian Orthodox Church,” he prayed.

In Ukraine, by contrast, leading churches including the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church of Ukraine had already appealed for resistance to the invasion. Even Metropolitan Onufriy (Berezovsky, b. 1944) of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, affiliated with the Moscow Patriarchate, called for prayers for the Ukrainian army and people and the defense of Ukraine’s sovereignty:

Defending the sovereignty and integrity of Ukraine, we appeal to the President of Russia and ask him to immediately stop the fratricidal war. The Ukrainian and Russian peoples came out of the Dnipro Baptismal font, and the war between these peoples is a repetition of the sin of Cain, who killed his own brother out of envy. Such a war has no justification either from God or from people.

The intertwined but separate religious histories of Russia and Ukraine have contributed both to the idea of the “one space” and to that idea’s being contested.

In heaven or on earth

Ukrainians, Russians, and Belarusians all trace their cultural and state origins to the early Rus principality that emerged in the ninth century around Kyiv. The medieval Primary Chronicle tells how Grand Prince Volodymyr (Vladimir in Russian) of Kyiv decided he needed an official religion to strengthen his rule. Living at a cultural crossroads, he considered Islam, Judaism, and Western Christianity before hearing from his envoys that they had not known whether they were “in heaven or on earth” when they visited the Byzantine Greeks’ services in Constantinople.

In 988 Volodymyr was baptized in the Greek city of Chersonesus then returned to Kyiv; he ordered the toppling of the statue of the pagan god Perun and the mass baptism of his people in the Dnipro River. To this day all Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches of the region regard the Kyivan baptismal font as their birthplace.

Volodymr’s decision set Rus on a geopolitical and cultural path with major implications. Certainly this became clear in 1054, a few generations later, when the Roman and Greek Orthodox branches of Christianity officially split over their significant differences.

One of the bones of contention was the way in which the church should be organized. The bishop of Rome, the pope, claimed universal supremacy over the whole church. By contrast Orthodoxy was and is a family of autocephalous local churches. Like the archbishop of Canterbury in the Anglican Communion, the ecumenical patriarch enjoys particular honor among patriarchs, but he cannot interfere in the internal affairs of other Orthodox churches.

More controversially Western historians claimed that the people of Rus absorbed—and would later perfect—the “Caesaropapist” model that made the emperor head of both the church and the state and supreme judge on religious matters. It would be more accurate to say that the Byzantine vision was one of “symphony” between the church and the state, in which the two worked together, each with its sphere of authority, and one did not dominate the other. But what symphony means in practice has been, and still is, one of the great questions in the history of the Orthodox churches.

Between 988 and 1240, the patriarchate of Constantinople saw Rus as a diocese and continued to appoint metropolitans to lead it. Only 2 of the 23 were natives of Rus; the rest were mostly Greeks. After the Mongols sacked Kyiv in 1240, the political and religious histories of the territories of northern and southern Rus diverged. Poland and Lithuania absorbed the lands to the southwest and southeast (modern-day Belarus and central and western Ukraine) by the 1360s.

To the northeast the upstart principality of Moscow gradually expanded control. The leading Rus’ churchman, the metropolitan of Kyiv, moved to Moscow; meanwhile, the ecumenical patriarch established new metropolitanates in Galicia and Lithuania.

In 1448 the Muscovite church rejected the Council of Florence’s plan to reunite Roman Catholics and all Eastern Orthodox. Its bishops consecrated their own metropolitan of Moscow and all Rus without the participation of the ecumenical patriarch, becoming essentially self-governing. After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Muscovy remained the only independent Orthodox state.

Russian churchmen developed a doctrine of theocratic monarchy, arguing that the other Orthodox realms had lost their independence by falling into heresy; therefore, Muscovy’s Orthodox tsar had a duty to uphold the purity of the faith. In 1589 the weakened ecumenical patriarch acknowledged the Russian Church’s autocephaly and enthroned a patriarch of Moscow and all Rus. Meanwhile a separate Metropolitanate of Kyiv with jurisdiction over the Rus of Catholic Poland-Lithuania remained under the ecumenical patriarch.

Fighting fire with fire

But all was not well for the Rus’ of the Polish-Lithuanian lands (Ruthenians, the ancestors of Ukrainians and Belarusians). Amid the pressure of the Catholic Reformation and hoping for renewal in 1596, Ruthenian bishops signed the Union of Brest. The resulting Uniate Church embraced Latin doctrine and recognized the supremacy of the pope, while preserving Eastern Christian liturgical traditions. However, strong Orthodox opposition to the Union arose, and the Ruthenian church split.

By 1632 Orthodox churchmen, determined to fight fire with fire, founded an academy along Jesuit lines in Kyiv; it quickly became the great intellectual center of Orthodoxy. Many graduates made their way to Moscow and became conduits of Western European and Ruthenian culture to the inward-looking Muscovite state and its elite. In 1667, after the Russo-Polish War, Muscovy took control of eastern Ukraine, parts of Belarus, and the city of Kyiv. By 1686 the metropolitan of Kyiv had agreed to place his church under the patriarch of Moscow rather than of Constantinople. After centuries of separate development, Ruthenian Orthodoxy now found itself in the “one space” of the Russian Church.

In the process, however, Ukrainian and Belarusian churchmen left a profound mark. For one thing the Kyiv Academy was developing the greatest minds of the Russian Church; and the new tsar, Peter the Great, who reigned from 1682 to 1725, relied heavily on its graduates. He had a radical program to build a secular absolutist monarchy to compete with other European states. To do so he needed the partnership of a reformed Orthodox Church.

Peter promoted Ukrainian churchmen whose learning he prized and who were generally more willing to support his reform agenda. In 1700 the patriarch died; rather than summon a council to elect a successor, Peter appointed Ukrainian metropolitan Stefan (Iavorsky, 1658–1722) as acting head of the church.

Peter envisioned a spiritual college of bishops, modeled on the state churches of Lutheran Scandinavia and Germany, to replace the patriarchate. In 1721 he established the Most Holy Governing Synod and called on the great Ukrainian scholar, preacher, and bishop Feofan Prokopovich (1681–1736) to draft the “Spiritual Regulation.” It required that clergy take an oath of allegiance, disseminate government information, and, most controversially, report sedition in their parishes.

In the following year, 1722, Peter created the office of chief procurator of the synod, a layman who served as the “tsar’s eye” in church affairs. Prokopovich saw the new model as a rejection of a Catholic-style “papal” patriarchate and a return to what he regarded as truly Orthodox collegial governance of the church. Indeed the church retained considerable autonomy in the eighteenth century, and the chief procurator’s office remained organizationally outside the synod.

The “one space” grew as the Russian state expanded. Between 1772 and 1795, Empress Catherine II (1729–1786), together with Austrian and Prussian emperors, carved up Poland among themselves.

Catherine justified this by claiming that Russia needed to reunify the Kyivan Rus lands to defend Orthodoxy and save the “Russian” population in Poland. In fact the Ukrainians and Belarusians of the region were Uniates, and their language and culture had diverged from Russian language and culture over centuries of separate development.

The incorporation of these territories involved an often violent campaign to “return” Uniates to their “native” Russian Orthodoxy. In 1839 1.5 million Uniates, including the majority of Belarusians, were “reunited” with Orthodoxy, and the Uniate Church was abolished in the Russian Empire. (Several hundred thousand remained in the Kingdom of Poland until 1875.) In Austrian Galicia, Uniates played an important role in Ruthenian (Ukrainian) political movements, but in Russia it was difficult to make religion a basis of national differentiation, since Ukrainians were regarded as “Russians” and fully incorporated into the Orthodox Church.

Official nationality

In the nineteenth century, both within and beyond the official church, Russians debated the relationship between church, state, and nation. To revolutionary movements across Europe that proclaimed “liberty, equality, fraternity,” Nicholas I’s (1796–1855) 1825–1855 regime asserted Russia’s fundamental distinctiveness as “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality.” Dubbed “Official Nationality,” this remained the state ideology until 1917.

However, the synodal system of church governance came under increasing criticism. In the 1830s and 1840s, an influential group of romantic nationalists, the Slavophiles, rejected Official Nationality and asserted the need to return to authentic Russian values—which, they said, resided in Orthodoxy and in the peasant commune, allegedly collectivist and cooperative, unlike the individualism and competition of the West.

Rejecting the bureaucratic Church of the Spiritual Regulation, Aleksei Khomiakov (1804–1860) argued that Orthodoxy’s strength lay in its spirit of sobornost’ (from the word sobor, or council), an idea of “active unity in plurality” such as that expressed by the commune.

Tension between Orthodox clergy and the state also worsened, in part because of increasing interference from the chief procurators and from Alexander III (1845–1894) and Nicholas II (1868–1918). Their chief procurator, Konstantin Pobedonostsev (1827–1907), emphasized the religious basis of tsarist authority. He wanted the clergy to play an active role in connecting the pious tsar and his devout and obedient people. However, the bishops chafed at his relentless interference and called for a return to the pre-Petrine model of regular bishops’ councils to govern the church. Similarly disenchanted parish priests mobilized to defend their interests.

During the 1905 revolution, the church worked to avert violence and to defend the existing order, but it also joined the population in calling for reform. Nicholas II’s 1905 manifesto on religious toleration, which made it legal to leave the Orthodox Church, became a crucial turning point. Tens of thousands of former Uniates in the Belarusian lands transferred to the Roman Catholic Church. The synod, against the wishes of Pobedonostsev, asked Nicholas II to convene a church council—the first since the seventeenth century—to address the church’s many problems and consider restoring the patriarchate.

In the semiconstitutional era after 1905, Orthodox clergymen served as deputies in all-elected dumas (parliaments), representing a range of parties. Even conservative churchmen became disillusioned with autocracy in the last years of the empire. Grigory Rasputin (1869–1916), a self-proclaimed “holy man,” had gained great influence with the imperial family and insinuated himself into church policy, encouraging Nicholas II to overrule the synod in various ways. Many clergy came to believe the church needed autonomy and collegial rule. When the monarchy collapsed in February 1917

(see pp. 6–10), the synod did not come to its defense.

New man on top

The new Provisional Government announced the convocation of the long-awaited All-Russian Council of the Orthodox Church. Across the country diocesan congresses of clergy and laity elected delegates to the council, hotly debating the relative power of laity, parish clergy, monastics, and bishops and arguing over whether to restore the patriarchate or a collective model of leadership. By November, following the Bolshevik seizure of power, the council elected a new patriarch, Tikhon (Bellavin) of Moscow.

Meanwhile movements for autonomy among various national groups of the former Russian Empire spilled into church affairs. Modern nationalism raised questions about Orthodoxy’s tradition of territorially defined local autocephalous churches. Should each nation have its own church? Some Orthodox in Georgia, Belarus, and Ukraine thought so and called for autonomy or even autocephaly, raising questions about the jurisdiction of the “All-Russian” Orthodox Church.

The Soviet and post-Soviet eras would further transform and complicate all these debates and questions in ways that the rest of this issue explores. Whatever Kirill may have prayed, the battle rages on. CH

By Heather Coleman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #146 in 2023]

Heather Coleman is a professor of Russian history at the University of Alberta. She is the author of Russian Baptists and Spiritual Revolution, 1905–1929, coeditor of Sacred Stories: Religion and Spirituality in Modern Russia, and editor of Orthodox Christianity in Imperial Russia.Next articles

Christian History TImeline: Christ and culture in Russia

Selected events from this issue and their context. (Underlined items represent the rise to power of some major political leaders.)

the editors