Bernard of Clairvaux’s labor of love

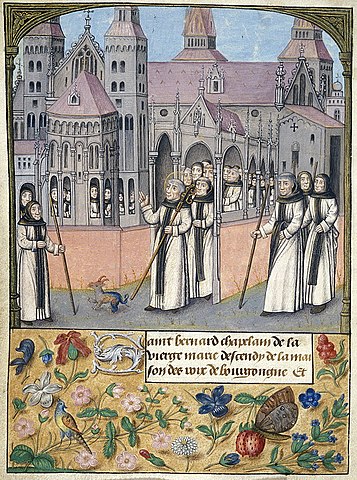

[Illumination from Chroniques abrégées des Anciens Rois et Ducs de Bourgogne. Southern Netherlands, c. 1485-1490. Collection: British Library, London, UK. Translation text: Bernard of Clairvaux, chaplain of the Virgin Mary leaving his house on his way to Burgundy. The church depicted is not Clervaux Abbey as is to be expected but the Church of Saint Servatius in Maastricht. Unknown 15th-century illuminator (attributed to: Master of the Trivial Heads) / public domain, Wikimedia File:K105354-Bernard of Clairvaux (British Library).jpg]

Admit that God deserves to be loved very much, yea, boundlessly, because He loved us first, He infinite and we nothing, loved us, miserable sinners, with a love so great and so free. This is why I said at the beginning that the measure of our love to God is to love immeasurably. For since our love is toward God, who is infinite and immeasurable, how can we bound or limit the love we owe Him? Besides, our love is not a gift but a debt. And since it is the Godhead who loves us, Himself boundless, eternal, supreme love, of whose greatness there is no end, yea, and His wisdom is infinite, whose peace passes all understanding; since it is He who loves us, I say, can we think of repaying Him grudgingly? “I will love Thee, O Lord, my strength. The Lord is my rock and my fortress and my deliverer, my God, my strength, in whom I will trust” [Ps. 18:1–2]. He is all that I need, all that I long for. My God and my help, I will love Thee for Thy great goodness; not so much as I might, surely, but as much as I can. —On Loving God

With eloquent and forceful writings on love, Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) led a revival of medieval monasticism. Throughout his surviving sermons, essays, and an extensive correspondence, Bernard’s theme of love embraces God’s love for us and our love for God, as seen in the union of Christ as the bridegroom and the soul as the bride in The Song of Songs. In his hundreds of sermons and other expositions of this theme, Bernard did not hesitate to identify his soul with the female bride, a rhetorical device common in his time. His eloquence inspired some later poetry that is often sung today: “Jesus, the Very Thought of You,” “O Jesus, Joy of Loving Hearts,” and especially the great hymn on Christ’s passion, “O Sacred Head, Now Wounded.”

Bernard’s emphasis on love even applied to “crusading as an act of love,” as historian Jonathan Riley-Smith put it; the people who were loved through crusading, in Bernard’s view, were the fellow Christians in the Holy Land. At the pope’s invitation and upon consultation with the French king, Bernard went on a preaching tour of France, the Low Countries, and up the Rhine to raise enthusiasm and troops for what was later called the Second Crusade—a flat-out failure.

Worship, work, wool, and honey

As a young man, Bernard joined and soon led the movement that reformed and revived Benedictine monasticism—namely, the Cistercians. By then all Benedictine communities, male or female, met for communal prayer many hours every day, singing through all 150 psalms every week. One male strand of the order, associated with the Abbey of Cluny, had for centuries emphasized worship so much that the new, young cohort wanted to restore the balance in St. Benedict’s original motto of “Worship and Work.”

Their energetic and creative labors on the land produced an enormous yield of crops, livestock, products (like wool and honey), and sheer real estate and institutional wealth, setting the stage for the next century’s revival—and for its emphasis on voluntary poverty by Francis of Assisi, among others (see pp. 28–32).

Meanwhile Bernard’s post as abbot of Clairvaux, the leading Cistercian community, led him to great authority in the church and thus in society as a whole. Mentor to popes, advisor to royals like King Louis of France and Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, arbiter of heresies, and author for the ages, St. Bernard was the “big dog” of the twelfth century.

By Paul Rorem

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #149 in 2023]

Paul Rorem is Princeton Theological Seminary’s Benjamin B. Warfield Professor of Medieval Church History, Emeritus, and an ordained Lutheran pastor; he is the author of volumes on John of Scythopoli and Hugh of Saint Victor in the Great Medieval Thinkers series and of Pseudo-Dionysius: A Commentary on the Texts and an Introduction to Their Influence.Next articles

Looking for the last emperor

Some medieval thinkers and writers sought reform because they thought the end was coming

Randolph DanielPoor in spirit, new in Christ

While they looked for renewal, the Waldensians looked like trouble

Alan KreiderPraying and preaching for a better church and society

Revival and renewal took many different forms in the High and late Middle Ages

Jennifer BoardmanChristian History Timeline: Reform, renewal, revival, reaction

Both clergy and laity sought a renewal of devotion and an end to corruption throughout the Middle Ages —but it was sometimes a bumpy road

the editors