First, preach Christ’s gospel

[John Hus preaching. Jenský kodex.—public domain, Wikimedia File:Hus na kazatelne.jpg]

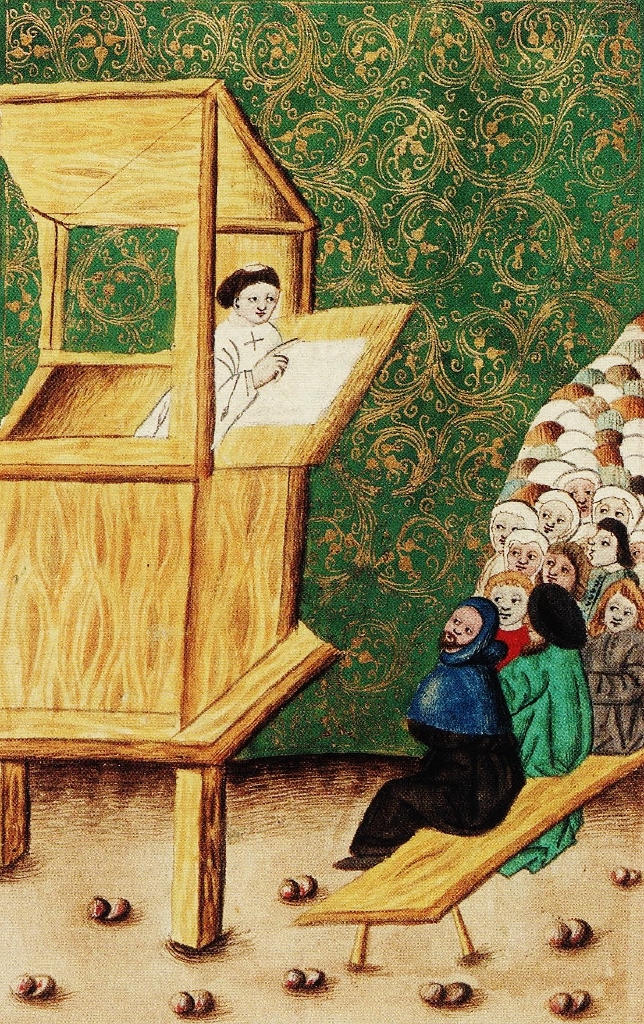

Thousands of people filled the church, with more spilling out into the street. Some chanted, “Jesus! Jesus! Jesus!”; some sang Psalm 132, rejoicing in their ability to meet as fellow Christians; some climbed onto their rooftops, hoping to catch sight of the spectacle. All had come to hear a superstar, albeit a controversial, preacher.

His sermon met their expectations. He preached the coming of tribulation, shouting the warnings of Old Testament prophets and the need for repentance. He preached the coming of a new millennium when tears would be no more and peace would reign. He exhorted the crowds that until then, they would have renewal and restoration of riches beyond their imagination if they turned to God, supported good government, and rejected prideful leaders.

Popular praise and worship

As modern as this spectacle sounds, it doesn’t represent an event at the Azusa Street Revival, or a preaching crusade of either George Whitefield or Billy Graham, or even a scene from a prosperity gospel megachurch in Texas or California. Conventional wisdom tells us it must have taken place after the Reformation era because sermons rooted in Scripture and delivered by charismatic clergy were a product of the religious changes wrought in the sixteenth century.

Except they weren’t.

In the last decade of the fifteenth century, a Dominican friar named Fra Savonarola (see p. 25) became the most popular preacher in the politically tumultuous medieval city of Florence. Crowds would swell the Duomo of Florence to hear him. Long before Hillsong a medieval version of praise and worship music often accompanied his sermons. Take for example these lyrics, probably sung for the first time in 1496:

Long live, live in our hearts Christ the king, leader and lord.

Let everyone purge his mind, memory, and will of earthly and vain affections.

Let all burn in charity, contemplating the goodness of Jesus, King of Florence.

Through fasting and penitence let us reform ourselves inside and out.

Similar laude, as they were called, from the same time ring with vibes reminiscent of modern Christian singer David Crowder. Instead of giving Jesus a “sloppy, wet kiss” as Crowder controversially sang in the original version of “How He Loves,” medieval singers proclaimed, “I feel myself melt when I look at my Lord who was born and dies for us, only to make us heir to heaven.”

Such lyrics proved particularly popular among Florentine youth who celebrated the preaching of Savonarola (both before and after his death) by marching through the streets singing. Thousands of young people (mostly boys and some girls) sang and shouted “Viva Cristo!” as they went.

Medieval mass media

The preaching of sermons provided a consistent refrain on both sides of the Reformation era—teaching and edifying in the central and late Middle Ages just as they teach and edify Christians today. Of course medieval and modern homilies show differences. Sermons, past and present, are dynamic texts, echoing the sounds of the world that creates them even as they narrate familiar biblical passages and themes.

Modern ears may not always recognize the cadence of medieval preachers, but even across the divide of the sixteenth century, their sermons follow the basic definition Beverly Kienzle offered in her book The Sermon: “an oral discourse spoken in the voice of a preacher who addresses an audience to instruct and exhort them on a topic concerned with faith and morals and based on a sacred text.”

Historian Pietro Delcorno described sermons as medieval “mass media” and emphasized both their popularity and persuasive power. Long before Martin Luther and John Calvin entered the scene, medieval clergy preached regularly not only to the choir (or other clergy) but also to the ordinary people within their communities.

By the year 1000, preaching in Western Europe was a regular component of Roman Christianity, albeit at that point mostly occurring in cathedrals and monasteries. A few sermon collections were composed (or translated) in vernacular languages, such as the Benedictine monk Aelfric’s sermons written in English in the early eleventh century, but most were preached in Latin and geared toward clergy.

Apostle to the apostles

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), a Benedictine abbess, provides a good example of medieval preaching before the thirteenth century. Hildegard’s pastoral preaching tour in Germany involved preaching in Latin mostly to clerical audiences in monastic spaces, but her sermons taught clergy how to be better pastors as well as grounding them in Roman Catholic orthodoxy. Thus, even though her immediate audience was clerical, the impact of Hildegard’s sermons extended to the broader church.

Hildegard is not a medieval anomaly. Women, fueled by the example of biblical women like Mary Magdalene, preached their way through medieval Europe: from the twelfth-century Hildegard to the thirteenth-century Marie of Oignies (1177–1213) and Rose of Viterbo (1234–1252) to even the fourteenth-century Catherine of Siena (1347–1380).

While it is true that reforming winds blowing between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries diminished women’s access to ecclesiastical authority, it is also true that stories of female preachers such as Mary Magdalene and monastic women like the seventh-century Hilda of Whitby (c. 614–680) swirled through the air of medieval churches even centuries later.

One can’t help but wonder if the memory of Mary Magdalene as the “apostle to the apostles” (as she was known to medieval Christians) strengthened Margery Kempe (p. 23) as she faced down the archbishop of York in the late fourteenth century, declaring that she would not stop teaching about God because Jesus himself had given women permission to speak (preach?).

Preach, pray, study, prove

The same reforms of the central Middle Ages that strengthened the celibacy and masculinity of the priesthood also strengthened the sermon as a didactic tool for teaching faith to ordinary people. The Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 defined the office of priest as “properly ordained according to the church’s keys, which Jesus Christ himself gave to the apostles and their successors,” and declared that sermons were important as “conducive to the salvation of the Christian people” and hence were necessary to be delivered by qualified clergy throughout the year. The council described clergy’s cura animarum (the cure of souls) as including both administering the sacraments and preaching sermons.

Two hundred years later, the clerical scribe who included notes on the office of a priest in Worcester Cathedral Library MS F. 172 was still emphasizing the significance of preaching: the five manners for the “office of a Bishop or a priest,” it stated, were first

to preach Christ’s gospel. The second is to pray to God continuously for the church. The third is the sacraments freely to make and bear to whom it behooves. The fourth is only to study in holy Scripture. The fifth is openly to prove and give example of perfection.

Instead of only sermons preached in Latin and geared toward clerical audiences, like those preached by Hildegard, sermons were now also preached in vernacular languages (English, French, German, etc.) and geared toward educating parishioners.

“Such mean clerics”

The popular sermons of John Mirk in the fourteenth century provide a good example not only of the framework of late medieval sermons but also of their popularity. An Augustinian prior from Lilleshall Abbey in Shropshire, who probably also served as a parish priest at St. Alkmund’s in the neighboring town of Shrewsbury, he wrote the sermon collection Festial sometime between 1382 and 1390 for the express purpose of helping clergy like himself.

“In help of such mean clerics, as I am myself,” he wrote in the prologue, “I have drawn this treaty from the Legenda Aurea [a collection of saints’ stories] with more adding to it. So he that desires to study therein, shall find ready for all the principal feasts of the year a short sermon needful for him to teach and others to learn.”

Organized to provide sufficient preaching material for the entire liturgical year, Festial contains 74 sermons written in English, arranged in chronological order, and appropriate for immediate delivery. Festial sermons were hand copied more than 40 times during the next 150 years, including by a savvy Dominican priest in the fifteenth century who sold his copies. Some of these copies were partial, with only a few sermons represented, but many were substantial and included most of the sermons.

Festial’s popularity persisted into the Reformation era; it was printed 23 times between 1476 and 1532, including by the first economically stable printshop in England owned by famous printer William Caxton. It is telling that out of the 110 books published by Caxton between 1476 and 1491, two were copies of Festial.

A trial record in the Borthwick Institute of York shows the last known preaching of Festial to be in 1582—50 years after the start of the English Reformation and 200 years after John Mirk penned the first Festial sermons. It would be centuries before The New York Times started tracking the sales of books, but if such a thing as a list of best-selling books existed in England between 1382 and 1532, Festial would have made the cut several times.

The hunger for a sermon cycle like Festial mirrored the public demand for preaching in the late medieval era. Ordinary parishioners had access to routine Sunday morning sermons (included with the Mass) and special event sermons preached outside the Mass by local clergy of larger churches and by preaching friars (Dominicans and Franciscans).

More opportunities to listen to sermons occurred during certain times of the year, such as around Easter, but the frequency of preaching increased across the board after the thirteenth century—including what we would probably call revival preaching, as exemplified by the opening example of Savonarola. The presence of famous preachers like Savonarola impacted local communities not only spiritually but also economically. Businesses would temporarily close as huge crowds gathered to listen to a celebrity preacher.

Saints and Scriptures

Some cities even reconfigured the architecture of their public spaces to accommodate larger sermon audiences. The Book of Margery Kempe hints at this importance of sermons in the lives of ordinary medieval people—showing the crowds who gathered with Kempe in the early fifteenth century to hear weekly sermons near her hometown of King’s Lynn.

Stories of saints and miracles filled the sermons they heard, but Scripture did too. More than 500 direct biblical references can be found in Festial sermons, and more than 900 can be found in the sermon compilation sold by the previously mentioned Dominican priest.

Medieval parishioners who listened to sermons would have learned their Bible in ways similar to modern Christians—especially the Psalms; the Old Testament narratives connected to the genealogy of Jesus; the birth, death, and Resurrection of Jesus; and the Gospel accounts. They would have been fairly well acquainted with the letters of Paul as well. The Book of Margery Kempe, for example, recounts how Kempe was inspired to go on pilgrimage to the Holy Land after hearing a sermon that preached Romans 8:31: “if God is for you, then who can be against you?”

In short, to dismiss the sermon as a product of the Reformation era is to misunderstand medieval Christianity. It also misunderstands the faith of medieval Christians who believed in the same Jesus professed by Christians today. CH

By Beth Allison Barr

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #149 in 2023]

Beth Allison Barr is James Vardaman Professor of History at Baylor University and the author of The Pastoral Care of Women in Late Medieval England and other books.Next articles

Dormant and exploding volcanos

Revivals kept breaking out in the Reformation—but sometimes when people didn’t want them to

Edwin Woodruff TaitWhat does it mean to live in Christ?

Reforming and challenging words from Martin Luther

Martin Luther and translatorsQuestions for reflection: Renewal, revival, and reform

Use these questions on your own or in a group to reflect on medieval renewal movements.

the editors