Chained bodies, freed souls

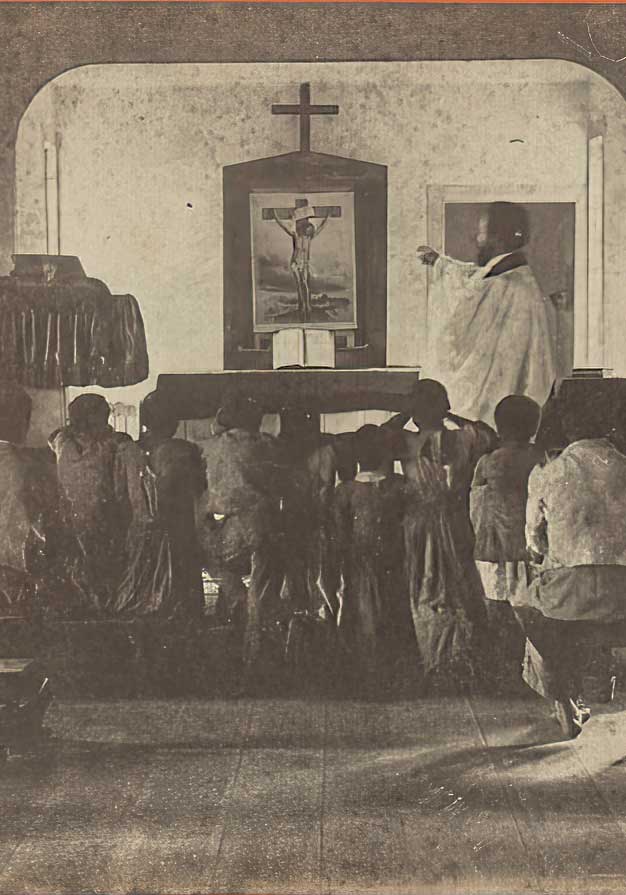

[Osborn and Durbec, Rockville Plantation Negro church, Charleston, S.C., 1860—Osborn and Durbec’s Southern Stereoscopic and Photographic Depot / Library of Congress]

This article from issue #33 captures the complex, honest, and sometimes difficult aspects of our history: people who claim faith don’t always act the way we hope they would.

By the Civil War, Christianity had pervaded the enslaved community. Not all were Christian or church members, but most found the doctrines, symbols, and vision of life of Christianity familiar.

Their religion was both visible and invisible, formally organized and spontaneously adapted. They paralleled regular Sunday worship in the local church with illicit prayer meetings on weeknights in the slave cabins. Church-licensed preachers hired by slaveholders were supplemented by slave preachers licensed only by the spirit. Texts from the Bible, which most slaves could not read, were explicated by verses from the spirituals.

Slaves often held their own meetings out of disgust for their masters’ corrupted gospel. Lucretia Alexander explained what they did when they grew tired of it:

The preacher came and . . . he’d just say, “Serve your masters. Don’t steal your master’s turkey. Don’t steal your master’s chickens. Don’t steal your master’s hawgs. . . . Do whatsomever your master tells you to do.” Same old thing all the time. . . . Sometimes they would . . . want a real meetin’ with some real preachin’. . . . They used to sing their songs in a whisper and pray in a whisper.

Slaves faced severe punishment if caught at secret prayer meetings. Moses Grandy reported his brother-in-law Isaac, a slave preacher, “was flogged, and his back pickled” for holding a clandestine service. His listeners were flogged and “forced to tell who else was there.”

To avoid detection slaves met in secluded places called “hush harbors.” Peter Randolph, enslaved in Prince George County, Virginia, until he was freed in 1847, recorded this description of a secret prayer meeting:

The slave forgets all his sufferings, except to remind others of the trials during the past week, exclaiming: “Thank God, I shall not live here always!” Then they pass from one to another, shaking hands, and bidding each other farewell. . . . [singing] a parting hymn of praise.

Many slaveholders ridiculed the notion of religion for slaves because they refused to believe Black people had souls, but others granted permission to attend church and encouraged religious meetings. Baptisms, marriages, and funerals were allowed on some plantations with Whites observing and occasionally participating, as well as annual revival meetings for all. Slaveholders often enjoyed their slaves’ singing, praying, and preaching. But the enslaved knew that slaveholder religion did not translate into freedom in this world.

Jubilant conversions

Baptism—especially for Baptists—was perhaps the most dramatic ritual in religious life. Dressed in white robes, the candidates proceeded “amidst singing and praises” and ecstatic behavior to the local pond or creek, symbol of the River Jordan, where each was “ducked.”

The slave preacher, leader of the slaves’ religious life and an influential community figure, presided over religious activities. Usually illiterate this preacher often had native wit and unusual eloquence. Carefully and suspiciously watched, the preacher straddled the conflict between the demands of conscience and the slaveholders’ orders. By comparison some preachers were privileged characters. They faced criticism from former slaves as the “mouthpiece of the masters.” However some also preached and spoke of freedom in secret.

In general the community understood the preacher’s restrictions. They respected him as a gospel messenger, one who preached God’s word with power and authority that sometimes humbled White folk and uplifted slaves.

Through spirituals, the Bible’s characters, themes, and lessons became dramatically real and took on special meaning for the slaves. Spirituals were not just words and notes on a page; they emerged as communal songs, heard, felt, sung, and often danced with hand-clapping, foot-stamping, head-shaking excitement.

Slaves believed that God would act within human history and within their own history as a peculiar people, just as he had acted on behalf of another chosen people, biblical Israel. That some slaves maintained their identity as people, despite a system bent on reducing them to a subhuman level, was certainly due in part to their religious life.—Albert J. Raboteau, from CH #33

By Albert J. Raboteau

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #150 in 2024]

Albert J. Raboteau (1943–2021) was Henry Putman Professor of Religion Emeritus at Princeton University and author of Slave Religion, from which his article is adapted.Next articles

Surprised by Christ

Three spirits conquered by Christ

Lyle W. Dorsett, Matt Forster, Kaylena RadcliffRussian Christianity and the revolution: what happened?

The sins of the church came back on its head with a fury

Andrew Sorokowski