Did you know? Awakenings

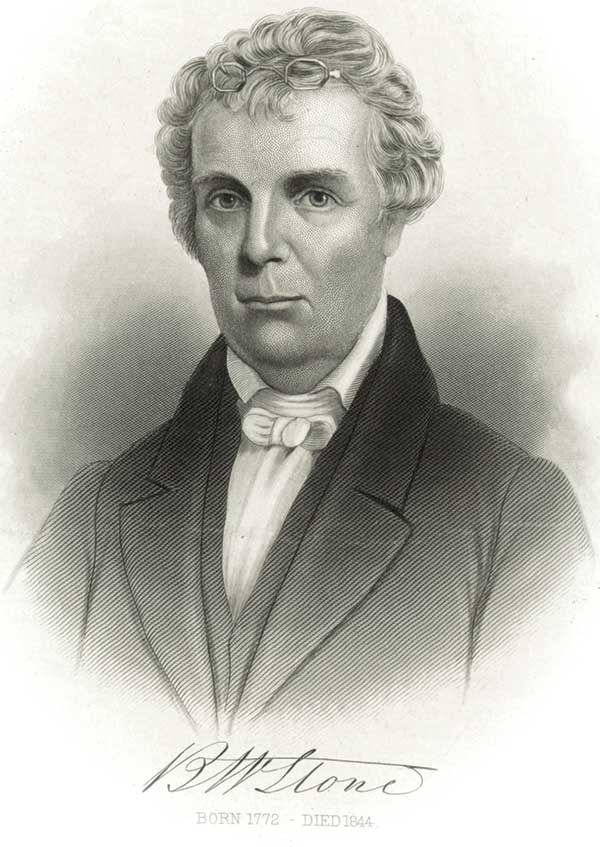

[Above: J. C. Buttre, Barton W. Stone in Pioneers in the great religious reformation of the nineteenth century, 1885, engraving—Library of Congress / Public domain, Wikimedia]

Portable preaching

George Whitefield (1714–1770) was known for his powerful preaching and ability to draw large crowds. He often preached in the open air, using a portable pulpit to deliver his sermons. Itinerant preachers commonly used portable pulpits during the First Great Awakening, allowing them to preach to large crowds in various settings. Whitefield received widespread recognition during his ministry; he preached at least 18,000 times to perhaps 10 million listeners in Great Britain and the American colonies. Whitefield was one of the first preachers to use print media to spread his message, publishing journals and sermons that were widely circulated.

Caught up into heaven

Jonathan Edwards, a leader of the First Great Awakening, was married to Sarah Pierpont (1710–1758). Pierpont had profound encounters with the Holy Spirit that caused her to faint, leap for joy, and lose her speech. Edwards recorded her experiences, writing:

They say there is a young lady in [New Haven] who is beloved of that almighty Being, who made and rules the world, and that there are certain seasons in which this great Being, in some way or other invisible, comes to her and fills her mind with exceeding sweet delight, and that she hardly cares for anything, except to meditate on him—that she expects after a while to be received up where he is, to be raised out of the world and caught up into heaven; being assured that he loves her too well to let her remain at a distance from him always.

Log cabin learning

Humble religious schools that operated in log cabins became known as “log colleges,” at first a denigrating term. During this time Presbyterian ministers could only be ordained if they had trained at an approved school, like Yale or Harvard. Log colleges trained new, revivalist-minded ministers and spread the gospel. William Tennent (1673–1746), a Presbyterian preacher, founded the first in Pennsylvania in the early 1700s. He wanted a place to teach his children. Out of his log college came the inspiration for and eventual founding of Princeton University.

Crows and Methodists

During the first half of the 1800s, the United States population exploded from about 5 to 30 million. Circuit riders, like Francis Asbury (1745–1816), reached many of them with the gospel. Over his 45 years in America, Asbury rode over 130,000 miles. Circuit riders often rode for five or six weeks straight, through heat and cold, rain and shine. People might say in particularly bad weather, “Nobody is out but the crows and the Methodists!”

Big tent revival

Camp meetings were a unique feature of the Second Great Awakening. These outdoor religious gatherings were often held in rural areas and attracted large crowds. They were typically organized as multiday events, when people came together in temporary campgrounds. Camp meetings featured passionate sermons, fervent prayers, hymn singing, and emotional expressions of spiritual experiences. People often testified about their conversions and shared their spiritual journeys.

Preaching prohibition

In the early nineteenth century, alcohol consumption was widespread and socially accepted. The average American over 15 years old drank at least seven gallons of alcohol annually: a level of consumption amounting, in many cases, to alcohol abuse. Preachers in the Second Great Awakening tackled this issue, helping to prompt the temperance movement. Those who urged moderation or complete abstinence from intoxicating liquor were called teetotalers.

Movers and shakers

During the Second Great Awakening, the “burned-over district” (western and central parts of New York state) was characterized by a series of religious revivals and the formation of new religious movements. The region was so named because it was said to have been so heavily evangelized that no one was left to convert. The religious fervor in the region also led to the formation of new religious movements, such as the Millerites and the Shakers.

Scouting ahead

Presbyterian Daniel Nash (1763–1837), also known as Father Nash, played a crucial role in Charles Finney’s (1792–1875) revivals as an intercessor. He traveled ahead of Finney and engaged in fervent prayer, sometimes for weeks, to prepare the ground for the revival meetings. Nash also organized and led prayer meetings during the revivals, interceding for the conversion of sinners and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Finney and others considered Nash’s ministry of intercession to be a vital component of the success of the revivals.

Awakening social change

Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) is said to have greeted Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896), the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, with the words, “So this is the little lady who made this big war.” Harriet Beecher Stowe was connected to the Second Great Awakening through her family and religious upbringing. Her father, Lyman Beecher (1775–1863), was a prominent Congregationalist minister and a revivalist who played a key role in the Second Great Awakening. Stowe’s Christian faith and commitment to social reform inspired her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a novel that exposed the evils of slavery and galvanized the abolitionist movement. CH

By Chris Rogers

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #151 in 2024]

Chris Rogers is the producer of Asbury Revival: Desperate for More and is working on a Christian History Institute miniseries on revivals.