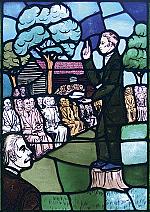

Rugged revival

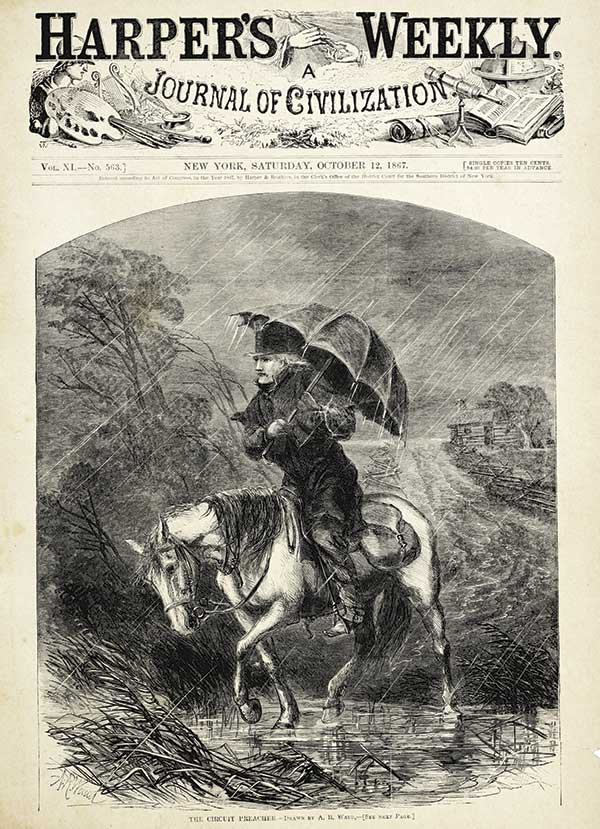

[A. R. Waud, The Circuit Preacher, 1867, Wood engraving—Public domain, Library of Congress]

In 1801 Colonel Robert Patterson (1753–1827) witnessed something incredible unfolding in rural Cane Ridge, Kentucky. Writing to a friend, he recounted:

On the 1st of May, at a society on the waters of Fleming creek . . . a boy, under the age of 12 years, became affected in an extraordinary manner, publicly confessing and acknowledging his sins, praying for pardon, through Christ, and recommending Jesus Christ to sinners, as being ready to save the vilest of the vile. Adult persons became affected in the like manner. The flame began to spread, the Sabbath following, at Mr. Camble’s Meeting House—a number became affected. The third Sabbath of May, on Cabin creek, six miles above Limestone, the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper was administered . . . about 60 persons were STRUCK down.

His letter (p. 41) goes on to describe thousands being struck down and begging Christ for forgiveness. Weeping, crying out, falling in the Spirit, and of course, the born-again experience set the tone for the revival at Cane Ridge and for all of nineteenth-century American revivalism. People came in the tens of thousands to experience the refreshment of the Holy Spirit and the hope of a promising tomorrow. Widespread in its geographic reach, such instances of revival, part of the Second Great Awakening’s impact, recast the 1800s as a Christian century in America.

So what was it about the Second Awakening that so profoundly shaped America’s religious identity? At least three factors played a significant role in this national spiritual revitalization: 1) the “democratization of American Christianity,” to use historian Nathan Hatch’s arresting interpretative phrase, 2) a form of revivalism that reached every farmhouse and backwoods community on the new American frontier, including enslaved African Americans, and 3) an eschatology of postmillennialism that drove the church to pursue a relentless path toward the improvement of American society and its institutions. These factors not only converted thousands of individual souls but baptized the United States into a functional Christendom.

Awakening a new nation

The Second Great Awakening followed on the heels of the birth of the American nation, a nation explicitly founded on the ideals of personal liberty and inalienable rights. The impulse toward greater personal self-determinism in American political culture, known as populism, received a significant boost with the election of the Tennessean Andrew Jackson in 1828. “Jacksonian democracy,” as it became known, elevated the “common man,” or the average American, and the frontier to new heights of importance.

It was in these frontier regions that individual and religious freedom took hold around the belief that the ordinary citizen no longer needed the guiding hand of elites, political as well as religious. Common people believed they could read and understand the meaning of the Bible just as well as any seminary-trained pastor or theologian, an understanding that only accelerated with the spread of the Second Great Awakening. This democratizing influence particularly elevated the religious role of women too, who experienced unprecedented opportunities, as historian Timothy Smith notes, to “participate in revivals and in testimony, prayer and class meetings, as often as not becoming spiritual leaders.”

As this populist strain developed within the American DNA, an explosion of new religious movements emerged and developed on the frontier regions of upstate New York and the American West. Older denominations such as Baptists and Methodists adapted to frontier culture, and new religious alternatives arose, such as Christian restorationism and enslaved African Americans’ increasing entry into the church. The Baptist polity of local church autonomy found a welcome home on the frontier where a populist mindset reigned. The yeoman work of the Methodist circuit riders left no frontier space untouched by the gospel, no matter how isolated.

Enslaved populations in America also found revival despite slaveholders who viewed religious gatherings on their plantations with suspicion—often shutting them down. Trying to control the message, they pushed a so-called “Slave Bible,” preaching only those passages that reinforced the obedience of the enslaved. But tucked away from the gaze of the overseer, a new and singular brand of Christianity began to form. Its more demonstrative worship practices included shouting, dancing, hand raising, “falling exercises,” and a new sacred music called Black spirituals. The influence of the Black worship experience made its way into the larger White revivalist meetings. William Black, a Methodist preacher, described the new revival atmosphere,

Under the sermon some began to cry out. I stopped preaching and began to pray. My voice was soon drowned. . . . About 30 were under deep distress, if one might so conclude from weeping eyes, heaving breast, solemn groans, shrill cries, self accusations, and serious reiterated enquiries “What shall I do to be saved?”

Unity at Cane Ridge

As the gospel message left the high steeple churches on the eastern seaboard and made its way to the frontier, evangelists became adept at speaking off the cuff and from the heart. Methodist bishop Francis Asbury exhorted his preachers to “preach as if you had seen heaven and its celestial inhabitants and had hovered over the bottomless pit and beheld the tortures and heard the groans of the damned.” America’s frontier also saw the emergence of new religious innovations, most notably the arrival of the camp meeting. What started in 1801 in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, as a gathering of people to take Communion, based on a practice developed in Scotland called a “Holy Fair,” soon ignited into a blazing revival. When John McGee took the preaching stand, he “exhorted [listeners] to let the Lord God Omnipotent reign in their hearts, and to submit to Him.” McGee reported the result, “the floor was soon covered with the slain.”

As word spread tens of thousands of people traveled from miles around to participate. Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists all took turns preaching. Cane Ridge helped develop a new fixture at revivalist meetings, multiple stages with multiple preachers placed around the meeting grounds. This interdenominational experience loosened the theological ties that bound denominational churches. Cane Ridge revealed a revivalist reality that would play out repeatedly in future revivals: a direct experience of the Holy Spirit superseding theological considerations that form denominations and divide the Christian body, if only momentarily.

Bright hope for tomorrow

This unusual display of unity at the Cane Ridge camp meeting caused one participant, Barton W. Stone (1772–1844), to begin the restorationist Christian movement (see CH #106). Restorationaism, later known as the Stone-Campbell movement, sought to return nineteenth-century Christianity to its original New Testament state. Eschewing traditional church creeds for the Bible alone, these religious innovators believed the preceding 18 centuries of Christianity had corrupted the true church of the first century. This restorationist impulse would influence other new religious movements during the rest of the nineteenth century, including radical Holiness groups and early Pentecostalism, both seeking to restore the Holy Spirit’s power and thus creating opportunities for new revivals.

Presbyterians like Charles Finney (see pp. 34–37) refashioned their staid denominational polity and piety to reach the frontier region of upstate New York. A trained lawyer with a fierce look, Finney passionately preached until resistance to the converted life retreated in defeat. He was placed on a “retainer from the Lord Jesus Christ to plead his cause,” and developed his own brand of revivalism. In his Lectures on Revivals of Religion published in 1835, he trained fellow preachers to act in a direct manner,

If there is a sinner in this house, let me say to him, Abandon all your excuses. . . . This very hour may seal your eternal destiny. Will you submit to God tonight—NOW?

Wrapped up in this heady optimism was an eschatological belief in individual and societal improvement, known as postmillennialism. The Second Great Awakening spread its teachings far and wide. Postmillennialism taught that the same gospel power that changed the heart of the individual could reform society. Methodist Bishop Gilbert Haven provided this summation of the effects of postmillennialism,

The Gospel . . . is not confined to a repentance and faith that have no connection with social and civil duties. The Evangel of Christ is an all-embracing theme. . . . The Cross is the center of the spiritual, and therefore of the material universe.

In America postmillenialist influence could be felt in the abolitionist movement, prison reform, relief for the poor, and temperance. Even in the first public universities in the Midwest, postmillenialist eschatology appeared in the institutional dedication to train Christians who could reduce the toil of labor and increase the production of agricultural and industrial goods, helping to bring about the millennial day.

The Second Great Awakening emerged from a democratizing culture of American individualism and self-determination that helped shape its style of revivalism. The camp meeting’s emergence and an eschatology of social improvement became the means to establish the new republic on a Christian foundation, even as it wrestled with the needed social changes to make this a reality. For the common person, the new birth of a nation combined with the new birth of the individual energized the American ethos with the rich possibilities of starting a new and better life. CH

By Joseph L. Thomas

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #151 in 2024]

Joseph L. Thomas is assistant professor of history of Christianity at Urbana Theological Seminary; cohost of the podcast Wayfinding; coauthor of a new book, Wayfinding with Dietrich Bonhoeffer; and author of Perfect Harmony.Next articles

“The flame spread more and more”

A firsthand account of the revival at Cane Ridge

Colonel Robert PattersonDivine disruption

Healing revivals of the nineteenth century fueled later Pentecostalism

Charlie SelfMore great awakeners

These unconventional figures preached the gospel and fomented revival

Jennifer A. Boardman