“Viva! Viva! Gesù!”

[Above: Philippe de Champaigne, Mère Angélique Arnauld, abbesse de Port-Royal, 1654, oil on canvas—Public domain, Wikimedia]

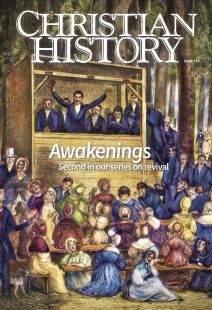

Though wars, conflicts, and persecution raged during the early modern period (c. 1600–1800), extraordinary missionary work and concentrated episodes of profound spiritual renewal also took place in Christian heartlands, from central Europe to the American colonies. Consider the lyrics of this eighteenth-century hymn:

Abel’s blood for vengeance / Pleaded to the skies;

But the Blood of Jesus / For our pardon cries.

Oft as it is sprinkled / On our guilty hearts,

Satan in confusion / Terror-struck departs.

Oft as earth exulting / Wafts its praise on high,

Hell with terror trembles, / Heaven is filled with joy.

Lift ye then your voices; / Swell the mighty flood;

Louder still and louder / Praise the precious Blood.

“Could Wesley have said more?” asked the English Catholic historian Sheridan Gilley, for these words come from a Catholic hymn, though they could be easily mistaken for a Protestant revival tune. “Viva! Viva! Gesù” (“Long Live, Long Live Jesus!”) is often attributed to

St. Alphonsus Liguori (1696–1787), founder of the Redemptorist Order. The common attribution has a logic to it, since Liguori’s Redemptorists became professional stokers of revivalist fervor around the Catholic world.

Amid the excitement of foreign missions, Catholics in Europe also felt compelled to evangelize their own house with a new sense of urgency. Out of this zeal, and partly in fearful reaction to Protestant success, were born the early modern Catholic parish “missions”—local efforts toward personal conversion and communal revival.

While aspects of the parish mission in this period (such as devotion to Mary) would have raised the eyebrows of any good confessional Protestant, the stereotype of a rote, spiritually moribund faith that did not put Jesus at the center is a false one. Whoever originally wrote “Viva! Viva! Gesù” understood the emotive, simple, and deeply Christ- and cross-centered piety that drove revival. Franciscan preacher St. Leonard of Port Maurice (1676–1751), for example, announced at the beginning of a mission that he “only intended to preach Jesus Christ and Him crucified.” For early modern Catholics, the grace of Christ was found not just personally but also communally, through sacraments and through public or private acts of piety such as praying the Rosary and walking the Stations of the Cross. Leonard’s efforts mainstreamed such acts of piety.

Contagious holiness

The decrees of the Council of Trent (1545–1563), intended to be the Catholic answer to the challenge of the Protestant Reformation, were slowly and unevenly implemented and sometimes simply ignored. However, the Council did provide a blueprint for those extraordinary Catholics who took the task of reform and renewal into their own hands. Maybe the most important of these was Charles Borromeo (1538–1584), a rich young aristocrat from northern Italy. Made a cardinal at 22 and archbishop of Milan at 26 by Pope Pius IV (his uncle), Borromeo could easily have fallen into the worst of the Renaissance-era playboy lifestyle. Thankfully, as a radical disciple of Jesus, his relatively short life provided an enduring model for the ideal “good bishop,” inspiring imitators from Poland to Mexico.

Catholic pioneers

Also contagious were the examples of the many men and women who pioneered new forms of religious life. The communities founded by Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556) and the Italian educator Angela Merici (1474–1540), for example, profoundly shaped early modern Catholicism (and still do). Women like Merici, organizer of the first group of Ursuline sisters, and Mary Ward (1585–1645), English founder of the Sisters of Loreto, carved out a place for active female witness through the vocation of teaching. Later, during the “Catholic Enlightenment” in the eighteenth century, a few extraordinary Catholic women were actually offered university professorships—something unheard of in the supposedly more advanced Protestant world.

Prospero Lambertini (1675–1758), archbishop of Bologna (the future Pope Benedict XIV), appointed physicist Laura Bassi (1711–1778) as the first female university professor in 1732. Mathematician Maria Gaetana Agnesi (1718–1799) was also offered a university chair in Bologna, but she elected to stay in her native Milan, combining intellectual pursuits with her commitment to philanthropy and her deeply emotive and Christocentric mystical writing.

Loyola founded the Society of Jesus (see CH #122). His Jesuits, following the example of his close confidante Francis Xavier (1506–1552), spread the gospel from South America to the Philippines to Japan. Early modern Jesuit missionaries such as Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) in China and Étienne de la Croix (1579–1643) in India laid the groundwork for numerous conversions. They also facilitated cross-cultural learning through their deep study of the traditions of the ancient societies in which they lived.

In this period Catholicism broadened from a primarily European religion to a truly global faith. The martyrs’ blood became the seed of new churches, from Canada to Uganda to Vietnam. Unfortunately, the legacy of early modern missions is closely connected to colonialism. Too often the missionaries aided and abetted oppressive and violent systems. However, in some instances heroic Catholics defended native peoples from the worst abuses of exploitative conquerors, as in the Jesuit “Reductions” in South America.

Back in Europe, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) had cemented religious division with legal force. No Catholic could live in denial any longer—Protestantism was here to stay. Thus, for a church that self-identified as “universal” (catholic), the success of early modern missionary efforts could not have been more timely. Though much ground had been lost (and regained) in Europe, the “universal” church now boasted vast multitudes of new converts from the Americas to the Far East.

Dynamic, infamous reform

Although Jansenism was named for the Dutch professor Cornelius Jansen (1585–1638), it was cradled in France. It became perhaps the most vigorous and controversial reform movement in early modern Catholicism. Initially concerned with reasserting what they viewed as the correct Catholic understanding of grace and predestination—laid out in Jansen’s massive commentary on Paul and Augustine—Jansenists were interested not just in technical theological squabbles but in personal conversion and wholesale church reform.

Jansenism’s epicenter was the convent of Port-Royal des Champs (outside Paris), which abbess Angélique Arnauld (1591–1661) had dramatically reformed. The formidable Mother Angélique was inspired by the shining lights of the golden age of French spirituality: Pierre de Bérulle (1575–1629), Jeanne-Françoise de Chantal (1572–1641), and two men that she knew personally, Francis de Sales (1567–1622) and the Abbé Saint-Cyran (1581–1643). The latter, a close collaborator with Jansen, eventually became the spiritual godfather of the Port-Royal nuns, further confirming them in a strict, Christocentric, and Augustinian form of Catholicism.

Jansenists championed women’s spiritual equality and the rights of lay Catholics to participate in public worship and access the Bible in the vernacular. Educated, confident, and endowed with iron wills, the Port-Royal nuns went toe-to-toe in theological debate with men, much to the consternation of the king and the archbishop of Paris. To paraphrase twentieth-century theologian Yves Congar, the Jansenists first articulated the principle of ressourcement (return to the “sources”) when they called Catholics back to Scripture and the early church.

For Jansenists understanding and participating in public worship and reading and meditating on the Bible formed the center of spiritual life. Vernacular translations of Scripture in Catholic Europe after the Reformation have a complex history. Opinions differed even within the same country. In France, for example, some Catholics supported Bible translations. Others argued that women were too spiritually and intellectually unstable to read the Bible. Others believed only theologically educated laity should have access, and some looked askance at all vernacular translations. Jansenists, however, consistently asserted not only the right of all the laity to have direct Scripture access, but the duty of all Christians to read the Bible if they could.

Scientist, philosopher, and apologist Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) became the most famous Jansenist. Pascal’s Provincial Letters, some of the wittiest satire in French, began as a defense of Antoine Arnauld (1612–1694), the leading Jansenist theologian and youngest brother of Mother Angélique. Antoine, called “the great Arnauld,” wrote powerfully against bans on vernacular translations. He railed against a prevailing interpretation of 2 Pet. 3:15–16 used to justify limiting women’s and uneducated people’s access to Scripture:

Horrible thought! Contrary to all of antiquity! Strange deprivation of the Word of God. It is a great lack of judgment to conclude from a passage of St. Peter that it is an abuse to allow Holy Scripture to be read by women and the unlettered [not reading Latin].

Some Catholics condemned Jansenism as mere Protestant innovation. Jansenists replied that their views on liturgy and Scripture were actually more Catholic and traditional than their detractors’ views. Their detractors were the innovators. Unfortunately, due to political machinations, their bitter conflict with the Jesuits, and their own imprudence and extremism, the Jansenists were repeatedly condemned by the French state and the papacy.

End of the old world

The debate over participation in the liturgy and vernacular Bible reading rolled on. In 1757 Pope Benedict XIV amended the Roman Index of Forbidden Books, granting permission to print and read vernacular Bibles as long as local bishops approved the specific translation. Benedict’s reform helped lead to the first approved Catholic Bibles in the countries with more restrictive policies. Sometimes, as in the case of Portugal, Jansenists and Jansenist sympathizers completed the Bible translations. But, in other cases, Catholics on good terms with the papacy promoted vernacular Scripture reading. For example, the anti-Jansenist archbishop of Florence, Antonio Martini (1720–1809), received a glowing letter of praise from Pope Pius VI when he completed the first edition (1781) of what became the Italian family Bible.

In the late eighteenth century, the Catholic Church was at an exciting but precarious place. Despite “official” condemnation, Jansenism had not only survived, it had adapted and spread around the Catholic world. Its reform agenda interacted fruitfully with others interested in change. But, fatefully, the most powerful Catholics were preoccupied with building nation-states based on Enlightenment principles. This resulting blend, sometimes called “Reform Catholicism,” reigned in Portugal, Austria, parts of the German- and Italian-speaking world, and throughout Spain, Naples, and Parma. It spread also to Central and South America and as far as Lebanon.

Reform, Rome, and revolution

Reform Catholicism’s greatest triumph came in 1773, when the pope had to suppress the Jesuits. The papacy had little defense against the agenda of Reform Catholics like Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II (1741–1790) and his younger brother Peter Leopold (1747–1792), who ruled Tuscany. Indeed, fruit had come from reforming efforts. Encouragement of Bible reading and Christ-centered piety spread, some priests experimented with the use of the vernacular at Mass, and attitudes toward Protestants and Jews softened. Unfortunately Reform Catholics excessively antagonized the pope and the religious orders, ran roughshod over cherished local beliefs and customs, and were too closely aligned with the state.

It all came crashing down in the French Revolution. In 1790 the National Assembly foolishly imposed an oath of allegiance on all the Catholic clergy of France, many of whom sympathized with the people’s grievances and the revolution’s original aims. This imposition forced an awful choice: loyalty to the pope or to the new government. It split the French church. Both sides, however, could find themselves at the steps of the same guillotine when anti-Christian fanatics hijacked the revolution during the “Terror.” The wars that the Revolution of 1789 unleashed dramatically altered the landscape of European political and ecclesiastical power. From the ashes of war and revolution, the Catholic Church emerged battered and reeling, but upright, its renewal story continuing, still crying, “Long Live, Long Live Jesus!” CH

By Shaun Blanchard

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #151 in 2024]

Shaun Blanchard is lecturer in theology at the University of Notre Dame Australia.Next articles

Recovering “true Christianity”

Pietism stood at the forefront of renewal in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

J. Steven O’MalleyThe awakeners

Before revival swept through the colonies, God was preparing key people around the world

Randy Petersen