“Don’t you want to be free?”

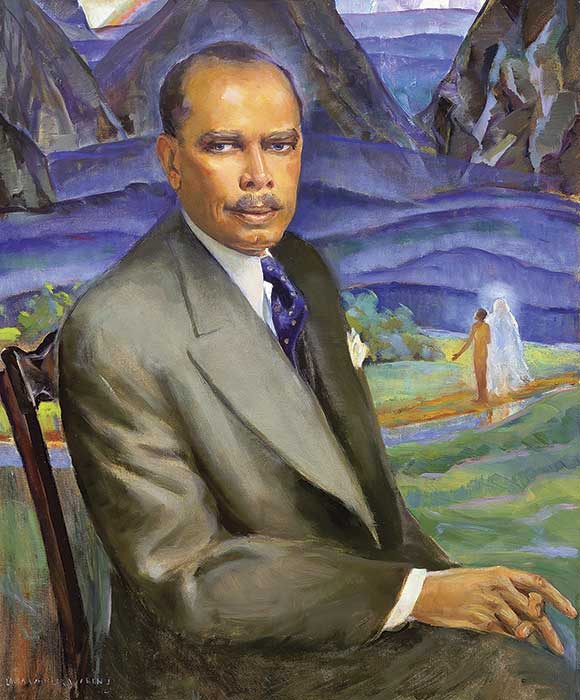

[ABOVE: Laura Wheeler Waring, James Weldon Johnson, oil on canvas, 1943—National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the Harmon Foundation]

The gospel story has had a robust and complicated relationship with African American theater. It might come as a surprise that the biggest hit on Broadway in 1930 was The Green Pastures, a retelling of Bible stories set in depression-era Louisiana, performed by a Black cast. Even before opening it sparked controversy. Some religious leaders saw the cigar smokin’ “Lawd” and Abraham and Noah as blasphemous.

More controversially the play’s romantic version of downtrodden but inspirational African Americans was written and directed by Marc Connelly (1890–1980), a White man. Despite a relatively positive response from some Black leaders, including W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), other cultural leaders challenged its version of longsuffering patience rooted in a Christian worldview. That lynchings were still going on in the American South, the play’s romanticized setting, and that cast members could not stay in segregated hotels while on tour demonstrated the play’s disturbing context.

DIGGING DEEPER

Around the same time, Black playwrights and performers were producing a body of work expressing a more complex view. From 1920 to 1945, they produced numerous plays highlighting religious themes, reflecting a serious dialogue about religion’s place for people no longer willing to have their “essence” explained by someone else. They refuted the “happy Negro” image, denouncing inequality, stereotyping, and injustice—embodying African American religiosity in ways that still drew upon the Bible.

Performed by an all-Black cast, Angelina Weld Grimké’s (1880–1958) Rachel, produced in 1916, was one of the first plays to protest lynching and racial violence. Rachel, the protagonist, refuses to marry and have children because of the racism she and her family face. The characters struggle with and revise their faith in a God who allows racism to prosper.

In another register altogether, James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) wrote God’s Trombones (1927), a poem-sequence based on traditional sermons, often turned into theater. Johnson’s apparent reversion to a sentimental, traditional faith creates a visionary passage to ecstatic wonder about both the creation and redemption of the world, reflecting the power of the greatest Story ever told, when told well, to lift and unite a community.

African American churches served as major staging grounds for Black religious drama, expressed through folk stories ranging from parodies of “District Conventions” to morality and mystery plays like Heaven Bound (1930) and In the Rapture. Time (August 10, 1931) praised the “morality play called Heaven Bound,” while Theatre Guild called it “the first great American folk drama.” Others contrasted it with The Green Pastures, calling it “a genuine all-Negro product . . . produced for religious instead of commercial purposes.” And it’s still running. In November 2023, audiences watched the play’s ninety-first production, making it the longest running stage performance in North America.

Langston Hughes (1902–1967), whose Don’t You Want to Be Free? (off Broadway, 1937) used the free-flowing, minimalistic, direct address style of the folk play for political purposes, later drew on the church pageant tradition in his commercially successful Black Nativity (1961). The ultimate folk production was Vinnette Carroll’s (1922–2002) Your Arms Too Short to Box with God, a musical retelling of Matthew’s Gospel, which opened Christmas 1976 and ran for 429 performances (and several revivals).

In mainstream theater Lorraine Hansberry’s (1930–1965) Broadway smash hit A Raisin in the Sun (1959) explores the conflicting aspirations of the Youngers, a Chicago tenement family. It offered responses to the situation of African Americans during the civil rights movement. Few moments in the play are as powerful as Mama Younger’s assertion, rooted in the faith sustaining her generation through racism and poverty: “In my Mother’s house, there is still God.”

At about the same time, actor and civil rights activist Ossie Davis (1917–2005) wrote and starred in Purlie Victorious (A Non-Confederate Romp through the Cotton Patch), a comedy about the South in the civil rights movement’s early days. The play tells of Reverend Purlie Victorious Judson returning to his home in rural Georgia to save its small church from the community’s segregationist “boss.” Premiering on Broadway in 1961, it ran for 261 performances. The recent Broadway revival is a smash hit, has been extended numerous times, and has garnered six Tony Award nominations. CH

LORD, LEAN OUT AND LISTEN

James Weldon Johnson called the poems in God’s Trombones “Sermons in Verse.” He set out to capture how, as he said in his preface to the book, “the old-time Negro preacher of parts was above all an orator, and in good measure an actor.” The poems have been set to music and performed theatrically numerous times.

O Lord, we come this morning

Knee-bowed and body-bent

Before thy throne of grace.

O Lord — this morning —

Bow our hearts beneath our knees,

And our knees in some lonesome valley.

We come this morning —

Like empty pitchers to a full fountain,

With no merits of our own.

O Lord—open up a window of heaven,

And lean out far over the battlements of glory,

And listen this morning.

—from “Listen, Lord: A Prayer”

And God stepped out on space,

And he looked around and said:

I’m lonely—

I’ll make me a world.

And far as the eye of God could see

Darkness covered everything,

Blacker than a hundred midnights

Down in a cypress swamp.

Then God smiled,

And the light broke,

And the darkness rolled up on one side,

And the light stood shining on the other,

And God said: That’s good!

Then God reached out and took the

light in his hands,

And God rolled the light around in

his hands

Until he made the sun;

And he set that sun a-blazing in

the heavens.

And the light that was left from

making the sun

God gathered it up in a shining ball

And flung it against the darkness,

Spangling the night with the moon

and stars.

Then down between

The darkness and the light

He hurled the world;

And God said: That’s good!

Then God himself stepped down—

And the sun was on his right hand,

And the moon was on his left;

The stars were clustered about his head,

And the earth was under his feet.

And God walked, and where he trod

His footsteps hollowed the valleys out

And bulged the mountains up.

—from “The Creation”

And God sat back on his throne,

And he commanded that tall, bright angel standing at his right hand:

Call me Death!

And that tall, bright angel cried in a voice

That broke like a clap of thunder:

Call Death!—Call Death!

And the echo sounded down the streets of heaven

Till it reached away back to that shadowy place,

Where Death waits with his pale,

white horses.

And Death heard the summons,

And he leaped on his fastest horse,

Pale as a sheet in the moonlight.

Up the golden street Death galloped,

And the hoofs of his horse struck fire from the gold,

But they didn’t make no sound.

Up Death rode to the Great

White Throne,

And waited for God’s command.

And God said: Go down, Death, go down,

Go down to Savannah, Georgia,

Down in Yamacraw,

And find Sister Caroline.

She’s borne the burden and heat

of the day,

She’s labored long in my vineyard,

And she’s tired—

She’s weary—

Go down, Death, and bring her to me.

—from “A Funeral Sermon”

In that great day,

People, in that great day,

God’s a-going to rain down fire.

God’s a-going to sit in the middle of

the air

To judge the quick and the dead.

Early one of these mornings,

God’s a-going to call for Gabriel,

That tall, bright angel, Gabriel;

And God’s a-going to say to him: Gabriel,

Blow your silver trumpet,

And wake the living nations.

And Gabriel’s going to ask him: Lord,

How loud must I blow it?

And God’s a-going to tell him: Gabriel,

Blow it calm and easy.

Then putting one foot on the

mountain top,

And the other in the middle of the sea,

Gabriel’s going to stand and blow

his horn,

To wake the living nations.

—from “The Judgment Day”

By The editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Next articles

“Were you there when they crucified my Lord?”

In liturgical traditions, such as the Orthodox Church, believers who participate in Holy Week’s drama enter into Christ’s passion.

Cyril Gary Jenkins