Did you know? Christianity and theater

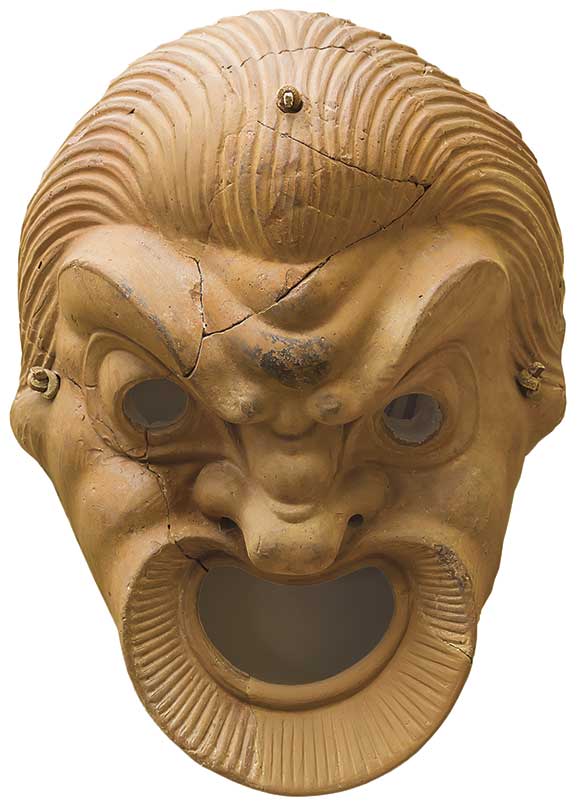

[Above: Terra-cotta comedy mask, c. 250 BC—Museum of the Ancient Agora / [CC0] Wikimedia]

FROM MOCKING TO MARTYRDOM

Genesius of Rome (d. 303) is acting’s patron saint; in legend he was an actor in the debauched Roman theater and came to faith as a participant in a performance in which the sacraments were being mocked. His sudden conversion led to his death at the hands of Emperor Diocletian (244 –311). He is also considered to be the patron of clowns, comedians, musicians, and dancers, as well as lawyers, epileptics, printers, and victims of torture.

HAPPILY EVER AFTER

People have sometimes restaged Shakespeare’s more tragic plays to give them happy endings. Restoration playwright Nahum Tate (1652–1715), best known to us today as a hymn writer, adapted King Lear into The History of King Lear (1681), the most performed version of the story until the early nineteenth century. It kept doomed heroine Cordelia alive and married her off to one of the few other heroic characters, Edgar; it also restored Lear to his throne. (Tate also adapted Coriolanus into The Ingratitude of a Commonwealth in 1682, though he did retain the death of the title character in that version.)

GOD'S DRAMATIST

As we’ve just explored in CH #151, revival preaching could be dramatic and theatrical (for more, see p. 25 in this issue). One of the most famous of the First Great Awakening’s dramatic preachers was George Whitefield (1714–1770). Here’s how Harry Stout described Whitefield’s impact in his biography The Divine Dramatist:

To appreciate Whitefield’s printed sermons fully, we have to read them less as lectures or treatises than as dramatic scripts, each with a series of verbal clues that released improvised body language and pathos. Words or phrases such as “Hark!” “Behold!” “Alas!” and “Oh!” invariably signaled the pathos Whitefield dramatically re-created with his whole body. The words were the scaffolding over which the body climbed, stomped, cavorted, and kneeled, all in an attempt—as much intuitive as contrived—to startle and completely overtake his listeners.

THAT TIME THE BIBLE WON A TONY AWARD

One of the most famous modern Christian-themed musicals is the controversial Godspell, based on the Gospel of Matthew and portraying Jesus’s teaching, passion, and death. It started as Episcopal playwright John-Michael Tebelak’s (1949–1985) masters’s thesis in drama at Carnegie Mellon in 1970 and was produced off Broadway in 1971. It ended up on Broadway in 1976, won the Tony Award in 1977, became a film (1973), was revived on Broadway (2011), toured around the world, and has been performed by hundreds of local theater groups. Composer Stephen Schwartz (b. 1948) was adamant that the show not portray the Resurrection, noting in the script “it is the effect JESUS has on the OTHERS which is the story of the show, not whether or not he himself is resurrected.” In practice many Christian groups that produce the show find a way around this restriction.

A MODERN SHEPHERDS' JOURNEY

Pastorelas, plays telling the story of the shepherds’ journey to the baby Jesus, originated in medieval Spain and later were brought to North and South America by missionaries (pp. 37–39). One of the most famous modern ones, first produced with puppets in 1975, was filmed with live actors in 1991 by PBS’s Great Performances as La Pastorela: The Shepherd’s Tale. The cast included numerous Mexican American celebrities—pop singer Linda Ronstadt (Archangel Miguel); comedian Paul Rodriguez (Satanas); Robert Beltran, later of Star Trek: Voyager (Luzbel); and Cheech Marin of controversial comedic duo Cheech and Chong (El Cósmico).

CAST LIST

Contributors to this issue have played a number of roles on stage themselves. Their Shakespearean roles include:

• Merchant of Venice: Portia, Bassanio

• A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Hippolyta, Theseus

• Much Ado About Nothing: Benedick, Leonato

• Romeo and Juliet: Friar Lawrence, Capulet

• Taming of the Shrew: Petruchio, Hortensio

• Twelfth Night: Maria, Sir Toby Belch

• Winter’s Tale: Time, Bear

Mystery and morality play roles include:

• “Creation”: God

• “Fall of Angels”: Satan

• “Fall of Man”: Adam

• “Cain and Abel”: Cain

• “Noah’s Flood”: Noah

• “Herod Play”: Herod

• “Joseph’s Trouble”: Joseph

• “The Temptation”: Christ

• “Harrowing of Hell”: Satan, Christ

• “Doomsday Play”: Tutivillus

• “Second Shepherd’s Play”: Coll, Gib, Daw, Mary, Mak

• Everyman: Everyman

• Mankinde: Mercy, Titivillus

Other faith-related roles include:

• And Then There Were None: Wargrave

• A Christmas Carol: Jacob Marley, Ghost of Christmas Present, Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, Mr. and Mrs. Fezziwig, Mr. Dilber

• Best Christmas Pageant Ever: Rev. Hopkins

• Charlotte’s Web: Homer Zuckerman

• End Days: Jesus/Stephen Hawking

• Freud’s Last Session: Sigmund Freud

• The Light Princess: Queen, Prince, Snake

• The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe: Mr. Beaver

• Little Women: Mr. March

• Love Divine: Charles Wesley

• The Pilgrim’s Progress: Narrator

• Pride and Prejudice: Mr. Bennet

• Proof: Robert

• Twelve Angry Jurors: Juror Eight CH

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Next articles

Letters to the editor: Christianity and theater

Readers respond to Christian History

Readers and the editorsEditor's note: Christianity and theater

My relationship with the theater has been ambivalent.

Kaylena RadcliffThe spectacle and the spiritual

How the early church interacted with Roman and Greek theater

David L. Eastman“Not consistent with true religion”

Tertullian penned one of Christianity’s oldest and most famous critiques of theatrical pursuits.

Tertullian