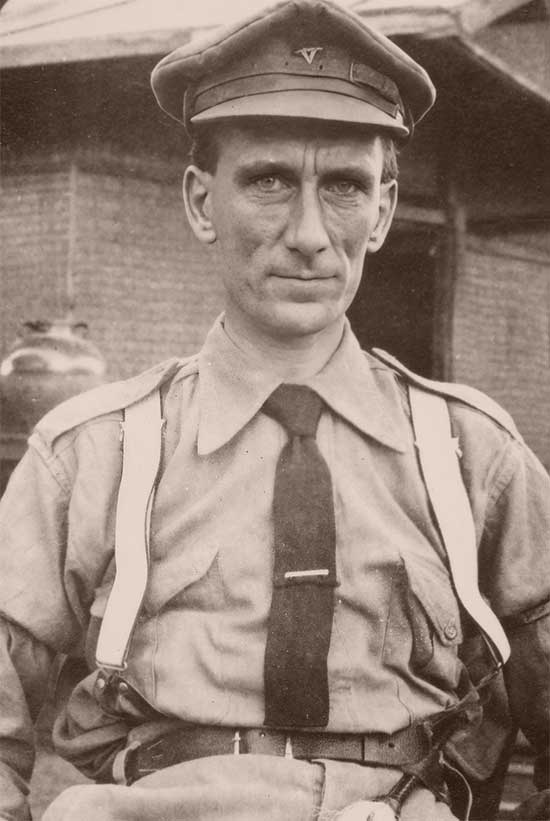

Oswald Chambers at war

[Above: Oswald Chambers in uniform, seated with fly whisk, September, 1917—Used with permission of the Oswald Chambers Publications Association, Ltd. / images courtesy of Wheaton Archives & Special Collections, Wheaton College, IL]

A grey, weird falling

Dark and drear and dense

With a soddened palling

Over every sense.

In dull ease drifting

Silent, slow, and still,

Just a steady shifting

From life, hope, and will.

A sure, sad sinking,

Scarce a gasp for breath,

After that no thinking

But the mind in death.

In September of 1896, Oswald Chambers penned these words while studying at Edinburgh University. “Hopeless” is just one of a handful of poems that Chambers wrote during his studies there and at Dunoon Bible College reflecting on a personal “dark night of the soul.” He struggled with inner emptiness as his hopes and dreams died. His overwhelming conviction of sins and false accusations from others plagued him (see inside front cover), and he couldn’t find peace with God.

Yet this dark night of his own soul had a purpose. It would prepare Chambers for the dark nights of thousands of others: soldiers entering the deadliest war the modern world had ever known.

FOR SUCH A TIME AS THIS

While at Dunoon Chambers regularly ministered with the Pentecostal League of Prayer, and yet he was also facing a complete breakdown. That all changed at a meeting in 1901:

I got up again and said, “I got up for no one’s sake, I got up for my own sake; either Christianity is a downright fraud, or I have not got hold of the right end of the stick.” And then and there I claimed the gift of the Holy Spirit in dogged committal on Luke 11:13.

I was as dry and empty as ever, no power or realization of God, no witness of the Holy Spirit. Two days later I was asked to speak at a meeting, and forty souls came out to the front. . . . and [I] went to Mr. MacGregor and told him what happened. He said, “Don’t you remember claiming the Holy Spirit as a gift?” . . . And like a flash something happened inside me.

During the 1904 Welsh Revival, Chambers realized the gospel transcended denominational and social lines. He took Jesus’s words as a personal clarion call: “Go ye into all the world and make disciples of all nations.”

Over the next decade as a League of Prayer speaker, Chambers taught, lived, and directed others into a living relationship with God. Through his travels, especially while visiting the Tokyo Bible Institute, he recognized the need for educating and spiritually training missionaries.

Chambers’s time spent in a dark night of the soul taught him the need to grow close to God and become a workman who was not ashamed of the gospel. With Biddy he established the Bible Training College (BTC) in 1911 to provide missionary training that drew others to Jesus.

As he wrote in So Send I You, “unless the life of a missionary is hid with Christ in God before he begins his work, that life will become exclusive and narrow. It will never become the servant of all men, it will never wash the feet of others.”

Chambers’s opportunity to apply spiritual convictions to the secular world came in 1914.

SIN IS WORSE THAN WAR

A month after World War I began, he wrote in Tongues of Fire magazine:

Is war of the devil or of God? It is of neither. It is of man, though God and the devil are both behind it. War is a conflict of wills either in individuals or in nations . . . Jesus Christ did not say: “you will understand why the war has come,”’ but, do not be scared, do not be in a panic. There is one thing worse than war, and that is sin.

At the BTC that fall, soldiers flocked to classes, friends went to war, maimed soldiers appeared on the streets. Oswald watched, prayed with Biddy, and by Christmas wrote, “the great war and the desperate spiritual need of our soldiers have been keenly present with us night and day since war began.”

Despite being 40 years old and thus exempt from military duty, Chambers closed the BTC in May 1915. He offered himself to the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) as a chaplain for “first aid spirituality.” As he wrote to his mother,

I have a strong impression that work with the YMCA will be the next thing. . . . He knows and I know He knows, and I know that I’ll never think of anything He will forget, so I just go steadily on as I have always done and He will engineer the circumstances.

Chambers traveled several months ahead of his family to the YMCA’s camp at Zeitoun. The “rough” camp boasted a large canvas tent and little else. The ministry involved providing morale opportunities for troops, primarily the 4th and 12th Australian Light Horse Brigades.

When Chambers announced a prayer meeting in the tent on his first night, everyone left. He preached anyway, and before long men began to join him. His practical and no-nonsense teaching worked in the hearts of men recently returned from Gallipoli. Needing hope and encouragement, they appreciated Chambers’s concerns for them.

Once Biddy, Kathleen, and BTC friend Mary Riley arrived, soldiers turned out in droves to drink tea, play with the toddler, and stay for prayer and teaching in the evenings. Many soldiers came to faith. Indeed, “it was almost worth enlisting to hear Oswald Chambers speak,” wrote one. Teaching straight from the Bible, Chambers preached the gospel. He wanted to ensure the troops understood who God was and why Jesus died for them before they faced eternity on the battlefield. Biddy took down everything he said during those meetings. She eventually turned the notes from Chambers’s study of Job into a book titled Baffled to Fight Better (see p. 21).

He didn’t shy away from difficult topics. One evening Chambers spoke on “Religious Problems Raised by the War.” On another he questioned, “What’s the Good of Prayer?” As a YMCA official wrote, “He was bubbling over with humor, a quality so essential in those war days, and his presence meant cheerfulness.”

Chambers recounted a conversation when a soldier said he couldn’t stand religious people. Chambers laughed. “Neither can I,” he said, and explained that spiritual reality meant everything to him. He wasn’t interested in religious “humbug.”

Just as Chambers knew from his dark night of the soul, soldiers needed to know about the radiant love God had for each of them. Many soldiers gathered to hear him. As a YMCA worker wrote about the evening Bible classes, “Mr. Chambers talked to them of spiritual things. They frequently crowded out the hut and stood outside to listen.”

Some nights the men spontaneously sang and shared testimonies. “It was an inspiration of the Spirit of God to listen to them,” Chambers wrote. Men often wanted to confess and receive absolution. He’d take them into the desert and kneel in the sand to pray with each one.

“One never gets used to the unspeakable wonder of a soul entering consciously in the Kingdom of Our Lord,” Chambers said. “A great joy.” YMCA director William Jessop appreciated Chambers:

His ceaseless activity, his wonderful insight into the real mind of the soldier . . . he desired to get to grips with each individual in the very heart of the battlefield—their own will.

Chambers saw Zeitoun as “an oasis of God.” He prayed through a lengthy list of soldiers’ names each day, often while watching the sun rise over the desert sands. When the soldiers headed “up the line,” into potential battle, they took Chambers’s ideas with them. They banded together into small groups to read and study the Bible in their tents at night.

AMONG THE SOLDIERS

In fall 1917 the army prepared to advance into the desert with hopes of taking Beersheba and then Jerusalem. Expecting many casualties, the army asked the YMCA to assign a chaplain to each unit.

Chambers was excited to go, purchased his needed supplies, and instructed Biddy on how to run the camp in his absence—including how to lead his classes. Right before departure, however, he fell ill with what he thought was a common stomach ailment. Chambers refused to visit the hospital, unwilling to take a bed from a wounded soldier. The delay in treatment cost him his life—he died at age 43 from complications after his appendix ruptured on November 17, 1917 (see pp. 11–13).

In the Middle East at that time, burials took place the same day. But the army, appreciating Chambers’s work with the troops, asked for a delay. They wanted to honor him with a military funeral. The following day 100 soldiers accompanied Chambers’s flag-covered casket on a gun carriage to the Old Cairo Cemetery. They carried their rifles pointing down as a sign of respect. He lies among the soldiers in a soldier’s grave to this day. The YMCA held a memorial service at Zeitoun. A thousand people crammed into the YMCA hut to remember Oswald Chambers. As a YMCA official wrote:

The realization came afresh with overpowering knowledge and conviction, even with our loss, that God was with us yet. Words of real testimony were given by different ones how, when groping in the dark, Mr. Chambers had guided them to Jesus Christ. Their testimonies were only a sample of what might be given by thousands of our fighting men.

Oswald Chambers knew about dark nights, troubled souls, and uncertain faith. He understood the hearts of soldiers trapped in circumstances they couldn’t change. He knew the only answer was found in the God who loved them.

Before he died Chambers reflected on the changes in his life. “My inner career at the beginning was heavy and strong. Now it is merging into a joy which is truly the receiving of a hundredfold more.”

As BTC student Katherine Ashe wrote, “He laid down his life finally because of the sheer exhaustion of all his physical powers” to make sure soldiers knew their God.

Well done, good and faithful servant Oswald Chambers. CH

By Michelle Ule

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #154 in 2025]

Michelle Ule is the author of Mrs. Oswald Chambers and a contributor to Utmost Ongoing.Next articles

Baffled to Fight Better

During the spring of 1917, Chambers spoke nightly on the book of Job

Oswald ChambersChristian History Timeline: Oswald Chambers

In His presence: the life and work of Oswald Chambers

the editors