Perspectives on Mercersburg

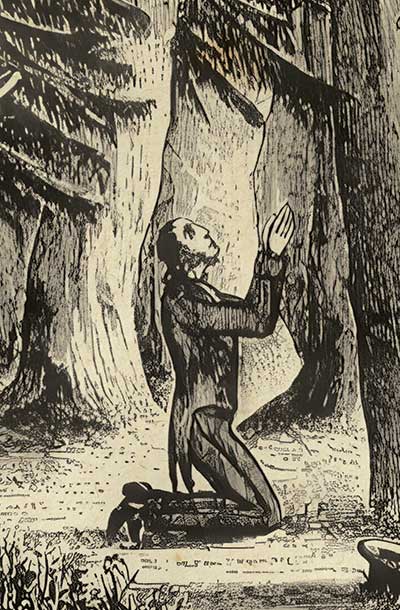

[C.B., The Conversion of Charles Finney, Unknown date—Public domain, The Gospel Coalition Blog / Enhanced by Doug Johnson]

The influence of Nevin, Schaff, and the Mercersburg movement was limited in its heyday, but a growing number of believers across denominational lines and faith traditions are encountering the movement and finding it has a lot to teach the church today. Christian History asked a few of those people some questions to find out more.

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is an author, senior editor of Christian History magazine, web editor for the Theology of Work Project, and a priest in the Episcopal Church. William B. Evans is an author, retired professor of Bible and religion, a retired minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA), and a member of the editorial board of The New Mercersburg Review. John H. Armstrong is an author, editor, mentor, and retired minister in the Reformed Church in America (RCA).

CH: What first drew you to the Mercersburg theology and movement?

WILLIAM B. EVANS: I first heard about Mercersburg when I was in seminary, when I happened to read The Anxious Bench by John W. Nevin. Having been raised in a pietistic evangelical context, I found Nevin’s emphasis on the objectivities of Christianity—the church and the sacraments—to be refreshing, and his critique of revivalist/conversionist subjectivity was remarkably insightful.

JENNIFER WOODRUFF TAIT: When I first discovered it, which I did about 25 years ago also through reading Nevin’s The Anxious Bench, it was a revelation to me that some of my own critiques of overly emotional megachurch culture had been anticipated by a soulmate from a century prior—and not only that, but a soulmate who was also a Protestant.

JOHN H. ARMSTRONG: In my early twenties, I had embraced a fairly rigid view of Reformed theology, but I soon saw how this divided the church into continuing divisions. When I came to see how important unity is for a healthy faith (cf. John 17:21–24), Mercersburg helped me understand this more clearly.

CH: What does Mercersburg mean to you spiritually?

JLWT: This is closely connected to the first question. I was raised in the 1970s–1980s Protestant mainline and deeply formed by college encounters with evangelicalism, and both of those traditions were pretty sacramentally thin. Through the Mercersburg writers, I came to realize that it was not illegitimate for me as a Protestant to be deeply drawn to sacramental and liturgical Christianity, and to the historical continuity of the church. I am forever grateful to them for this realization, which has guided me spiritually for the last 20-odd years.

JHA: It helped to free me from fear and rigid confessionalism.

WBE: Yes, I have found it liberating! It frees one from the pressure to “gin up” some sort of religious experience, or to conform to some particular morphology of conversion.

CH: What would you say the core guiding principle of the movement was, if you had to distill it down to one sentence?

JHA: Christ saves through his person, not by theories of theology.

JLWT: Right. And Christianity is not about your feelings, but about an objective encounter with the living Christ, whom we encounter through the historic church and experience in the Eucharist.

WBE: Without doubt the central principle or dogma of Mercersburg is the Incarnation. In other words it’s all about Jesus! Nevin and Schaff were convinced that God has indeed stepped into history, and that the Incarnation introduced a new, decisive, and transforming reality into human existence.

CH: What would you recommend people read to understand more about what Nevin and Schaff in particular were getting at?

JLWT: For Nevin, the two books that blew the top off of my head were The Anxious Bench, as I mentioned, and The Mystical Presence, which is one of the best books about the Eucharist I’ve ever read. I haven’t read all of Schaff’s History of the Christian Church, but what I have read has been deeply formative on my own historical thinking and writing.

WBE: It’s always best to get one’s theology straight, though some good secondary studies are available. Three key texts by the principal figures provide a solid introduction to the movement. First, as Jennifer said, there is The Anxious Bench. Second, there is Schaff’s presentation of a developmental approach to church history in his The Principle of Protestantism. And third, there is Nevin’s defense of a sacramental approach to Christianity—The Mystical Presence: A Vindication of the Reformed or Calvinistic Doctrine of the Holy Eucharist. Note that all three of these texts emerged within a three-year period of intense theological creativity! And all of these texts are now available in modern critical editions as part of the Mercersburg Theology Study Series.

JHA: And besides, of course, these actual works of Nevin and Schaff, I recommend William B. Evans, A Companion to the Mercersburg Movement. Cascade, the publisher of this book, is still publishing volumes from the movement.

CH: Why do you think the sacramental/liturgical/ecumenical approach of Nevin and Schaff (for example, their views about the relationship between Protestantism and Catholicism, and/or about the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist) was met with such opposition from other Reformed thinkers in the nineteenth century? Do you see any parallels with church struggles today?

WBE: In their context Nevin and Schaff were both accused of “catholicizing.” This was a period in which traditional Protestant antipathy to Rome coalesced in toxic ways with nativist opposition to Catholic immigration and anything that seemed to smack of Catholicism (e.g., the notion that the sacraments might actually do something) provoked deep suspicion. Moreover much of American Protestantism had moved in a profoundly individualistic direction and was shaped by a philosophy [Scottish common sense realism; see “How to speak ‘Mercersburg,’” inside front cover] that had little room for mystery.

Nevin and Schaff were advocating for an “evangelical catholicism” that drew from the best of early, medieval, and Reformation Christianity. Thus they were able to retrieve a corporate, churchly, sacramental sensibility and liturgical worship in ways that continue to speak powerfully to the church today, if we will listen. To the extent that American Christianity, particularly in its evangelical form, is ahistorical and ecclesiologically challenged, Mercersburg continues to be relevant.

JLWT: I think the fear of people sliding down a slippery slope toward Catholicism led many Protestants in the nineteenth century (in general, not just Reformed ones) to draw sharp boundaries around what constituted acceptable forms of Protestantism—boundaries that were much more stringent than the boundaries drawn by the Protestant Reformers themselves. (This is basically Nevin’s argument in The Mystical Presence.) I think it behooves us to ask ourselves today if we are ruling out orthodox, historically grounded Christian doctrines and disciplines because we think they will make us look too much like groups we fear.

JHA: Yes, I see clear parallels with that today. The dominant American expression of Reformed theology in the nineteenth century was focused on opposition to Catholic theology and the “presence of Christ” in the Eucharist. This is still the case in many modern movements. Mercersburg helps open the door to the new ecumenical movement happening in our time.

CH: Are there any organizations, groups, or conferences active today that explore the legacy of Mercersburg?

WBE: A Mercersburg Society was formed in 1983 by a group of pastors, scholars, and laypeople who wanted a forum to discuss the Mercersburg theology and its potential implications for today. The impulse here was never merely historical; they were convinced that the Mercersburg ethos has something to say to the challenges of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The society hosts an annual Mercersburg Convocation and publishes The New Mercersburg Review.

JHA: And while it is small, the Mercersburg Society still carries considerable influence. I had the privilege of spending time scanning the great collection of original resources at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, some years ago.

CH: The Mercersburg movement was a nineteenth-century phenomenon. What limitations or challenges do you see in bringing a Mercersburg perspective to bear on the twenty-first-century church context?

JlWT: Fewer than you might think. While it’s important to understand the historical context of any movement, it’s also important to remember that Christians from the past are our brothers and sisters in Christ grappling with similar problems of doctrine and discipleship (end of Christian History editor soapbox). I think the Mercersburg emphasis on a historic, structured, rational, sacramental faith has a lot to say to the modern church.

JHA: Yes, but I think the challenge of the past remains. Can we embrace theological perspectives that will allow us to seek oneness in our common faith?

WBE: Right. There are at least two challenges here, and I explored these at some length in my book A Companion to the Mercersburg Theology. First, Nevin and Schaff were both deeply influenced by German idealist philosophy, which gave them intellectual tools for thinking in more corporate, sacramental, and developmental ways. Of course most people today are not followers of Hegel and Schelling! I would argue that Nevin and Schaff used idealism as a tool without being slavishly devoted to it.

Second, Nevin in particular was rather elitist and hierarchical in his thinking, and that sort of thing provokes deep suspicion from many today. Nevin was troubled by the sectarian chaos of the American Protestant Christianity of his day (in which any Tom, Dick, or Harry could start their own church), and his rather hierarchical view of the church was his way of trying to impose some order. But this hierarchical and somewhat mechanical view of church authority actually stood in tension with Nevin’s focus on the Incarnation. Nevin’s contemporary, Alexis de Tocqueville, perhaps said it best when he wrote, “All the great writers of antiquity were a part of the aristocracy of masters, or at least they saw that aristocracy as established without dispute before their eyes . . . and it was necessary [for] Jesus Christ [to] come to earth to make it understood that all members of the human species are naturally alike and equal.”

CH: What do you personally think is the most lasting legacy of Mercersburg?

JLWT: I think the most lasting legacy of Mercersburg is the space it carves out for those of us who are deeply sacramental, deeply ecumenical, deeply connected to the church and its traditions, and deeply Protestant. (I owe much of my fervent Eucharistic piety to John and Charles Wesley, to be sure, but I owe most of the rest of it to John Williamson Nevin.) I believe that interest in the Mercersburg theology persists because people wearied by today’s religious heirs of Finney’s New Measures still find in Nevin’s and Schaff’s writings a guide to finding, and living, a saving life in Christ.

WBE: For me the legacy of Mercersburg is not so much a set of particular theological propositions (though I often find myself agreeing with Nevin and Schaff). Rather, it is an ethos, a way of doing theology, a “habitus” as classical theology would term it. The Mercersburg theology took Scripture, and the tradition of the church, and the ongoing doxological, liturgical life of the church seriously to address the needs of their time. We can certainly learn from that today! CH

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait, William B. Evans, John H. Armstrong, and the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

Next articles

Recommended resources: Mercersburg movement

Learn more about the Mercersburg movement’s main figures, critics, influences, and legacy with these recommendations from Christian History’s authors and editors.

the authors and editorsQuestions for reflection: Mercersburg movement

Questions to help you reflect on the legacy of the Mercersburg movement

the editorsDid you know? What Happened to the Apostles?

Though often creatively hyperbolic and of dubious origins, apostolic legends have inspired believers through the ages

the editorsLetters: What Happened to the Apostles?

Readers respond to Christian History

our readers and the editors