Legacy and longevity

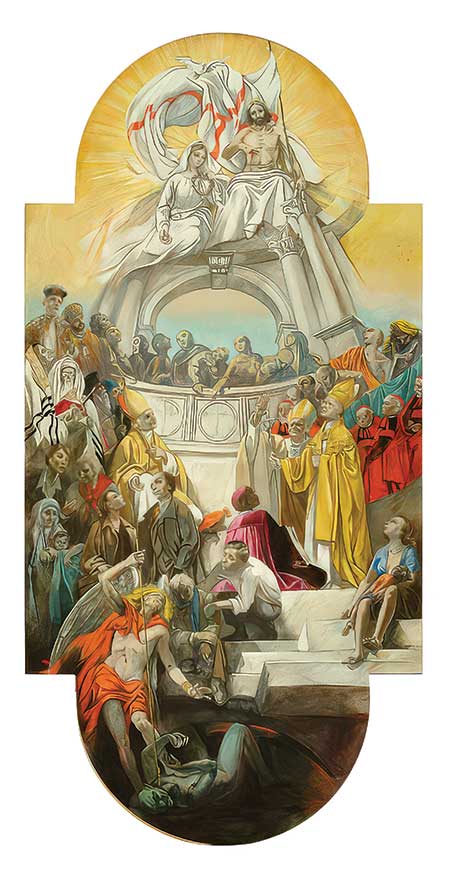

[Ernani Costantini, Second Vatican Council, Jesus Christ the Redeemer and Saints. 2002—Diocese of Padua / [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0] Beni Ecclesiastici in WEB]

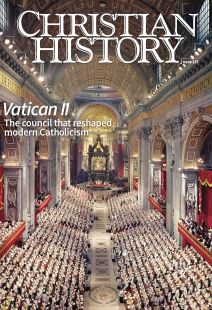

The Second Vatican Council concluded on December 8, 1965. Sixty years later, it still has widespread implications that go far beyond the inner life of the Catholic Church. Christian History talked to two historical theologians, one Catholic and one Protestant, for more on the consequences and interpretations of Vatican II. Lucas Briola is associate professor of theology at Saint Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Carl R. Trueman is professor of biblical and theological studies at Grove City College in Grove City, Pennsylvania.

Christian History: Debates about Vatican II have often centered on the question of “continuity” vs. “discontinuity.” What would you say was the main way in which Vatican II changed Catholicism—genuinely offered something that hadn’t been there in the tradition before, or hadn’t been explicitly or fully worked out?

Lucas Briola: The primary achievement of Vatican II was its quite explicit articulation of the “universal call to holiness,” a call for all Christians to belong more fully to Christ (see Vatican II’s Lumen Gentium, chap. 5). As John O’Malley memorably says in his magisterial history of the council, “For the first time in history, a council insisted on the ‘universal call to holiness’ and made clear that promoting that call was what the church was all about.” While other councils assumed that holiness and some spiritual writers described that holiness prior to the council, Vatican II put that call front and center of the church’s life. Moreover, it is that call that organizes and explains its other more noticeable achievements, like the organic interplay of Scripture and tradition as Christ-mediated, active participation in the liturgy, an empowered episcopate (bishops), the legitimacy of the lay vocation, a commitment to ecumenical and interreligious dialogue, and a constructive engagement with modernity.

Carl R. Trueman: I would rephrase the question. The intention of the council was not, first and foremost, to wrestle with the question of continuity or discontinuity but to apply the church’s teaching to the challenges posed by modernity. This included the rise of religious pluralism, the challenges posed by postwar European culture, the growing loss of cultural status and influence for Christians, and the threats posed by alternative ideologies, whether intellectual or more broadly sociological. Clearly any answers to these challenges were inevitably going to be scrutinized in terms of continuity and discontinuity with established dogma and practice, but that was not the primary purpose.

CH: What major sign of continuity—something the Second Vatican Council emphasized or brought about—do you think was fully in keeping with the existing tradition?

CT: The council exhibited many points of continuity. Perhaps most important was the office of the papacy. In Lumen Gentium the council affirmed the primacy of Peter and the pope of Rome as his successor. That is continuous not only with Vatican I but with centuries of Catholic teaching.

LB: The central question that the council faced—namely, the widespread secularization brought on by modernity—matched the questions faced by the earliest Christians: how do you proclaim Christ to a world that knows little about him, hates him, or ignores him? To root our own discipleship in that question is paramount; otherwise, we become complacent and lose our evangelical fervor. It is a question that the council can return us to.

CH: Is the major need in Catholicism today for more continuity, more appreciation of the council’s radicalism, or some third possibility?

CT: Much depends on how one interprets the council. There are those who see it as essentially a repristinating (restoring) and renewed application of traditional Catholicism to modernity. Others see it as justifying some radical breaks with aspects of that. The role of Cardinal Newman’s concept of doctrinal development, itself subject to contested interpretations by traditionalists and progressives (see pp. 45–49), is central to this. So strange as it is to say, before this question can be answered, Catholics themselves need to come to a consensus on how to understand the council.

LB: Councils take a long time to digest, and we aren’t there yet with Vatican II. The Council of Trent took at least a hundred years! Today there stands a need to consolidate the gains of Vatican II in view of the pontificates since the council—especially Popes John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis. How might we integrate a robust Christocentrism with, say, a radical commitment to resolving social injustices? How can we overcome the various polarizations that have plagued the Catholic Church since the council? In many ways I think this work of consolidation will be a key priority of the newly elected Pope Leo XIV.

CH: If you could go back in time and change one thing about either the council itself or its consequences, what would it be?

LB: I know it sounds very insignificant, but I would join the famous British anthropologist Mary Douglas (1921–2007)and say that I would have maintained the Friday abstinence (from meat) rules that marked preconciliar Catholicism. Leading up to the council, the eating of fish on Fridays throughout the year had served as a Catholic shibboleth, a key boundary marker that set Catholics apart. In the council’s aftermath, even while the council itself said nothing about these rules, the bishops relaxed those rules. Not only was this change—along with the liturgical reforms—the most palpable experience of the Vatican II Council for most Catholics, it came to stand for precisely what the council did not intend: an iconoclastic dilution of Catholic identity amid the waves of modernity. Interestingly in our time of ecological catastrophe, some Catholic bishops have recently called for the restoration of Friday abstinence.

CT: There were Protestant observers at the council who were invited to attend the public sessions and were able to contribute to the theological discussions, but they (understandably) had no vote. I would have liked to see a higher profile given to these voices, though I am not sure how that could practically have been achieved.

CH: Dr. Briola, what one aspect of Vatican II or its effects is most important to your own faith?

LB: For me, the council’s identification of the liturgy—especially the Eucharist—as the source and summit of the Christian life (see Sacrosanctum Concilium, paragraph 10) has shaped my faith and theology in profound ways. It invites me to think about how the church’s worship might shape everything I do, and how might everything I do find its fulfillment in the church’s worship. It serves as a continual reminder that the most primary work of the church is the praise of God; all else follows from there.

CH: Dr. Trueman, how does Vatican II affect your evaluation of Catholicism as a Protestant? What’s one way in which it was, in your view, a move in the right direction, and one in which you think it was a mistake?

CT: On the positive side, Dei Verbum and Sacrosanctum Concilium affirmed the need for the laity’s access to, and reading of, the Bible—and actively encouraged this for personal Christian growth, as well as paving the way for more Scripture to be read in formal church services. That was a very welcome development and has encouraged me as a Protestant to realize that many committed lay Catholics are now biblically literate (and have worship services where more Scripture is read than in many of their Protestant equivalents).

On the negative side, the council, given its ecumenical authority, could have superseded or even revoked the anathemas against Protestantism of the Council of Trent. It did not do so, and therefore those anathemas remain in place, as part of the church’s infallible teaching.

CH: What do you think is the most common misunderstanding people have about the council?

CT: That it represents a radical break with the past and a deep opening up of Catholicism to alternatives.

LB: For its boosters and detractors respectively, there runs the risk of rendering the council as either an accommodation or a capitulation to modernity. Against both those misinterpretations, the council’s primary intention was to transform the world through the paschal light of Christ: the true lumen gentium!

CH: Do you think the church should call another ecumenical council in the near future? Why or why not? What should be on the agenda if so?

CT: Yes and no. Clearly there is a need for the church to clarify in an official way what Vatican II means today. But there is also the danger that another council might simply deepen the problems rather than solve them. Catholicism seems so fragmented internally that any council is likely to reflect that.

LB: While I would never place bets against the Holy Spirit, I doubt we will see another ecumenical council in our lifetime. Vatican II itself will continue to need time to mature in the life of the church. Moreover Pope Paul VI’s recovery of the Synod of Bishops and Pope Francis’s emphasis on synodality for the entire church means that the sort of consultation an ecumenical council represents is happening more regularly in Catholicism. Nevertheless the questions raised by something like artificial intelligence over the next several decades point to an ongoing need for theological reflection and magisterial guidance. Whether something like an ecumenical council is needed for that work is an open question. CH

By Lucas Briola, Carl R. Trueman, and the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Next articles

Recommended resources: Vatican II

Learn more about the Second Vatican Council with these resources written and recommended by our authors and editors.

the editors and authors