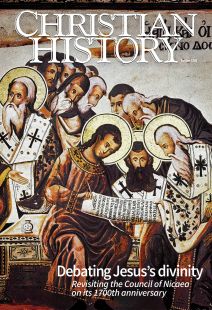

CH 158 timeline: debating Jesus's divinity

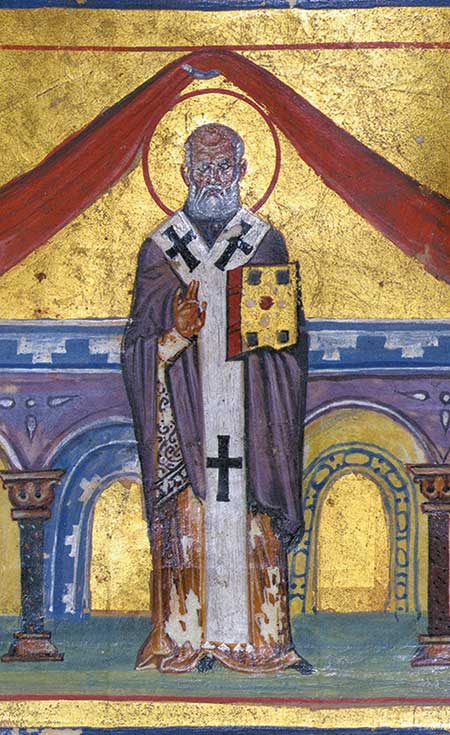

[ABOVE: Detail from Gregory the Theologian Illumination in “Imperial” Menologion. MS W.521, fol. 234v. 11th Century. Constantinople—The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore]

—303 The “Great Persecution” begins under Emperor Diocletian.

—313 The Edict of Milan, issued by Roman emperors Constantine I and Licinius, extends religious freedom to all, including Christians.

—c. 318 A theological dispute between Bishop Alexander of Alexandria and one of his presbyters, Arius, sparks a storm of correspondence and public controversy.

—c. 320 Athanasius, a student of Alexander, writes On the Incarnation.

—324 Constantine defeats Licinius and becomes the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. He sends a letter to Alexander and Arius pleading with them to set aside their differences.

—325 The Council of Antioch supports Alexander’s views against Arius, deposes Eusebius of Caesarea, and plans a general council to be held in Ancrya. Constantine moves the council to his palace in Nicaea.

—325 The Council of Nicaea produces a creed affirming that Christ is of the same substance as the Father and condemns the teaching of Arius. Eusebius of Caesarea is reinstated. Arius and his supporters are exiled.

—326 Alexander selects Athanasius as his successor before he dies.

—328 Athanasius becomes bishop of Alexandria. Over the next 17 years, Athanasius faces periods of exile and controversy.

—336 Constantine attempts to reinstate Arius. Arius dies before he is received back into fellowship.

—337 Constantine is baptized on his deathbed by Eusebius of Nicomedia.

—337 Constantius II, one of three coemperors after Constantine’s death, embraces Arianism. The Nicene Creed is nearly eclipsed amid a dizzying array of councils and creeds for several decades.

—c. 340 The Arian missionary Ulphilas evangelizes the Goths.

—350–53 After a civil war, Constantius becomes sole ruler of the empire.

—350s Tensions build between heterousian and homoiousian theologians (defined below in “Doctrinal Dysfunction”).

—359–360 Emperor Constantius calls two councils that promulgate a homoian creed.

—361 Constantius dies; Julian the Apostate becomes emperor.

—360–380 Pro-Nicene theologians rally around the Nicene Creed as an orthodox alternative to Arian creeds.

—370 Basil becomes bishop of Caesarea and repudiates “fighters against the Holy Spirit.”

—373 Athanasius dies.

—378 Basil dies.

—379 Theodosius the Great becomes Roman emperor.

—380 Basil’s brother, Gregory of Nyssa, refutes the heterousian writings of Eunomius. Gregory of Nazianzus preaches a series of protrinitarian sermons in Constantinople.

—381 The Council of Constantinople, summoned by Emperor Theodosius, reaffirms and expands the Nicene Creed.

—451 The Council of Chalcedon proclaims the two natures of Christ. After this, the church looks to the Council of Nicaea as the beginning point for establishing orthodoxy.

Canonical conundrum

The Council of Nicaea’s attempt to appeal to Scripture revealed a fundamental difference between Alexander and Arius: how they believed Christians should interpret biblical statements about Christ. Alexander and Athanasius appealed to scriptural texts that speak of the Son’s generation from the Father or that declare the unity of Father and Son:

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. (Col. 1:15)

I and the Father are one. (John 10:30)

The Son is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact representation of his being, sustaining all things by his powerful word. After he had provided purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty in heaven. So he became as much superior to the angels as the name he has inherited is superior to theirs. (Heb. 1:3–4)

Arius drew upon Scripture passages that speak of the Son being distinct from the Father, particularly texts that speak of profound differences between the two:

The Lord brought me forth as the first of his works, before his deeds of old. (Prov. 8:22)

… for the Father is greater than I. (John 14:28)

Now to the King eternal, immortal, invisible, the only God, be honor and glory for ever and ever. Amen. (1 Tim. 1:17)

According to Athanasius, the council’s endeavor to settle upon the right terminology to describe Jesus’s relationship to God the Father began with the many different scriptural titles for Christ. How were they all to be read? Word, Power, Wisdom, Angel of the Lord, Servant, Morningstar, Son of David, and Son of Man are some of the important Old Testament titles given to the Son. Son, Word, Lord, Power, Light, Shepherd, Imprint of God’s Nature, Life, Rock,

and Door are some of the important New Testament titles given to the Son. Were all of these titles given in the same way or in the same sense? Was Jesus the “Word” in the same way he was the “Door”? Furthermore, were these titles given in a unique way to Jesus? Was Jesus called the “Son of God” as the Israelites were called sons of God and those who believed in Jesus were now the sons and daughters of God? Was God Jesus’s “father” in just the same way he is “our father”?

—Michel Rene Barnes, Associate Professor of Theology Emeritus, Marquette University

Doctrinal dysfunction

Nicene orthodoxy was defined in this way: the Father and the Son are of the same essence (homoousios); but they are not different “parts” of God. God is indivisibly One yet Three. Here are definitions of positions that differ from Nicene orthodoxy and are considered heresy, or a departure from biblical Christianity. Pay close atten-tion to the seemingly small but crucially significant differences in the Greek words:

Homoiousian: The Son is like the Father in essence (homoiousios); he differs from the Father only in not being unbegotten.

Homoian: The Son is like the Father, but he is a distinct and inferior being.

Heterousian (or Euno-mian): The Father and the Son are unlike in essence.

Eusebian: There is a closeness between the Father and the Son, but they are distinct beings.

Modalist (or Sabellian): God’s names (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) change with his role or “modes of being” (like a chameleon). When God is the Son, he is not the Father. There is no permanent distinction between the three “persons” of the Trinity, otherwise you have three gods.

—By the editors

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #158 in 2026]

Next articles

Creed, chaos, and consensus

The rise of the pro-Nicene alliance and Trinitarian understanding

Mark DelCogliano