The idea of Christendom

FOR MANY modern Westerners, the idea of “Christendom” functions like popular Internet quizzes that claim to diagnose personality disorders. The idea has served its purpose once you have figured out if you have a case of “Christendom” or not and the degree of doom you and your companions may therefore look forward to.

Degrees of doom vary. Modern writers alternately claim that Christendom is being returned to, should be returned to, can never be returned to, never existed in the first place, never disappeared, is violent, is nonviolent, is a metaphor, or is a bad idea. To its detractors, the word evokes cynical church people using church language to get power. To its defenders, it stirs nostalgic longing for a time when doing Christian things required far fewer daily negotiations with non-Christians.

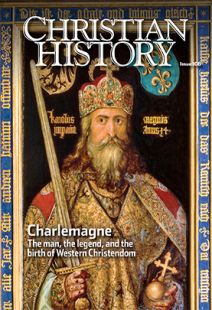

Whatever is meant by “Christendom,” though, people seem to agree that medieval Europe had it in abundance. Among the first people to think so was medieval monk Alcuin, adviser to Charlemagne, who contrasted Europe’s past chaos with the Christianized social order he’d helped to build: “Although the whole of Europe was once denuded with fire and sword by Goths and Huns,” he wrote, “now, by God’s mercy, Europe is as bright with churches as is the sky with stars.”

Fire and sword?

Yet it turns out that much of medieval “Christendom” was an explanation after the fact—starting with Alcuin. The Roman Empire didn’t exactly “fall”; it developed chronic congestive heart failure and was no longer able to do what it had done in days of hardier circulation. And Goths didn’t exactly invade, at least at first. Rather, they sought and secured refuge within the Roman Empire from the Huns. Violence occurred later, when the Goths revolted in response to exploitation they experienced in their refugee settlements.

Moreover, the Carolingians—the medieval Frankish dynasty that reached its height of power under Charlemagne—did not see their own war-making as part of a “civilization clash” between Christians and Muslims (“Saracens,” they called them). The Saracens were just one among many enemies of Christian rulers, including Lombards, Saxons, Normans, and Danes.

The story of “Christendom” really begins with a massive shift that occurred when the Roman Empire ceased to function as a center of power for western Europe. Prior to that, it had served, in Peter Brown’s description, as the “crude but vigorous pump” whereby anything that happened economically happened on a large scale. But over the course of the fifth century, that pump lost its prime and its parts stopped functioning. Goods ceased to move. The economies of western Europe became markedly local.

Christianity stepped in to fill the gap, the unifying force in a Europe that lacked any other center. During the 300 or so years between Rome’s fading empire and Charlemagne’s rising one, western Christianity proved highly portable and adaptable to local custom. For a while it was able to unite different regions into a coherent theological world—a world where God ruled over all, and the heavens were crowded with saints.

But could that unity hold? Even as western Europeans believed they were simply speaking local dialects of Latin, vernacular languages—Spanish, German, French, Italian—were taking shape. Many Christians knew only an oral version of their faith, since they and everyone else they knew were illiterate. What was to stop someone from preaching—whether through ignorance or malice—an unrecognizable version of Christianity? Regional expressions of the church were one thing. Mutually incomprehensible and contradictory versions were another.

Putting it back together

Such was Charlemagne’s worry after his rise to power. It led to the program he called correctio—putting things back into order—and which others would call the “Carolingian Renaissance.” Charlemagne saw his work as akin to Old Testament king Josiah (2 Kings 22), whose rediscovery of the Book of the Law made faithfulness possible.

Charlemagne and his advisors thought their own day heralded a providential “rediscovery.” They spoke, for the first time, of “barbarian invasions” of Goths and other tribes into the Roman Empire—and claimed this was a distinct historical period from which Europe was now emerging, thanks to the special favor in which God held the Franks. A triumphant sentiment, but it had a note of anxiety. If Europe ever ceased to have as many churches as the sky had stars, then God’s favor might well be withdrawn.

This was the beginning of the notion of “Christendom.” The word itself, an Old English vernacular word, originally meant simply “Christianity.” But it came in the Middle Ages to have the sense of “the Christian world” or “lands where Christianity is dominant.”

For Charlemagne and his advisors, and for those who followed, it meant that uniformity of Christian practice was insisted on from the top down, as the main way of warding off the disintegration of the church into a jumble of churches, isolated in their own regions. It meant uniformity of control over a Christian empire. Or did it?

Through pieces of legislation like his Admonitio generalis, or “general warning”—a set of 82 laws about church government—Charlemagne insisted upon centralized church oversight. The bleak consequences of imperial disfavor fell upon any who failed to follow the instructions (See “The man behind the empire,” pp. 8–15).

But in matters unrelated to church governance and practice, Charlemagne consulted with the leading figures of each region, typically allowing local law to carry the day. This was diplomatically prudent, but also contained clever politics. In allowing local law to hold sway in matters unrelated to church practice, Charlemagne set up Christian law as the only law actually uniting all the different subjects of his empire.

Correcting and instructing

In such a diverse empire, it was essential that people not merely obey the laws, but also understand them. How did Charlemagne do this? Unlike the centralized approach of the Byzantine Empire (where all roads ran through Constantinople), Charlemagne’s correctio infiltrated the empire through a large class of learned, aristocratic clergy and monastics scattered throughout the empire. To them fell the responsibility of ensuring that Christian texts were copied correctly so that less literate clerics could recite them without error. A local priest’s mistake, after all, could lead an entire region astray.

The Admonition generalis singles out for concern those “who want to pray to God in the proper fashion, yet they pray improperly because of uncorrected books.” Alcuin tried to simplify all kinds of important theological books from antiquity—rewriting Augustine’s Commentary on John, for example. Many passages of Augustine’s writing were left intact, but many were taken out and replaced with other writings or with Alcuin’s own commentary. People responded. Particularly in Germany, local towns competed with each other to show their assent to the requirements of correctio.

Charlemagne could not foresee that his attempts to unite a fractured society would have such far-reaching impact. Though his dynasty petered out, his idea that church and state belonged naturally together—and that together they would hold back the barbarians from the gates—lasted long after Leo set the crown on his head that fateful Christmas Day.

It lasted through long lines of popes and Holy Roman Emperors outmaneuvering each other. It lasted through a Reformation in which reformers found their own ways to make governments Christian, even while protesting against the wreck they thought Catholicism had made of medieval government. It lasted as Christianity spread across the Atlantic to a new land, the United States, that had no state church but saw the state itself as carrying out God’s mission on earth.

Long after Charlemagne’s empire crumbled, long after no one remembered the 82 clauses of his general warning or competed to earn the favor of his bishops and abbots, people throughout Europe—and indeed all of the West—would still be wondering: Is our nation as bright with churches as the sky is with stars? And if it is no longer, should we praise or lament? CH

By Sarah Morice-Brubaker

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #108 in 2014]

Sarah Morice-Brubaker is assistant professor of theology at Phillips Theological Seminary.Next articles

Christian History Chart: Not your parents’ Middle Ages

The Middle Ages had many renaissances before "The Renaissance"

the EditorsAlcuin of York

Alcuin reformed education at court and established a palace library

Jennifer Awes Freeman