Christ and the remaking of the Orient

[MacArthur in the Philippines—Wikimedia]

THE SUN FLOWED through the low-hanging clouds above the USS Missouri. Tokyo Harbor was abuzz with hundreds of military vessels, all awaiting the unconditional surrender of Japan. September 2, 1945, was a day that so many at home had prayed for. This ceremony marked the official end of almost four years of hostilities between the Allied Powers and the Axis Powers. World War II was now left to history.

The man who returned

At first the Japanese had refused to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, a statement calling for unconditional surrender on their part. They were unwilling to have their emperor disgraced by his submission to a foreign power. In response President Harry Truman ordered the Enola Gay to drop an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6.

The Supreme War Council of Japan still refused to surrender, hoping for more favorable terms. Three days later a second bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki. Surrender negotiations were immediate.

At 9:00 a.m. Tokyo time, representatives of the allied nations gathered. General Douglas MacArthur stepped forward to sign the Japanese Instrument of Surrender as the supreme commander of the Allied Forces Pacific (SCAP). This was his moment in history. He had promised to return when his forces retreated from the Philippines in 1942, and here he was. He had promised an unconditional surrender, and it occurred.

D. M. Horner, an Australian Army officer, said of MacArthur’s presence at the signing, “It was fitting recognition for a general whose contribution to the Japanese defeat had been surpassed by few others and for a nation which had borne an unsurpassed burden.” As SCAP MacArthur now enjoyed an unprecedented mandate from the United States government to make whatever changes he felt necessary to reconstruct postwar Japan. After the Japanese dignitaries departed from the Missouri, he made a radio speech that included the lines:

Military alliances, balances of power, leagues of nations, all in turn failed, leaving the only path to be by way of the crucible of war. We have had our last chance. If we do not now devise some greater and more equitable system, Armageddon will be at our door.

The problem basically is theological and involves a spiritual recrudescence [revival] and improvement of human character that will synchronize with our almost matchless advances in science, art, literature and all material and cultural development of the past two thousand years. It must be of the spirit if we are to save the flesh.

MacArthur and many others in the United States viewed this as a great opportunity not just to modernize governments in Asia, but to influence their cultures through Christian principles, affecting the lives of millions.

A lifelong Episcopalian, MacArthur was a man of quiet and reserved faith. Many of his troops attested that they never saw him attend church. Yet in the dark days of WWII, MacArthur prayed for wisdom and success in the battles that he led. Leading chaplains, bishops, and other Christian religious leaders visited him frequently, and he believed that for secular government to succeed, it must be rooted in the moral standards, human rights, and ethical principles of Christianity. MacArthur firmly held that the American experiment in democracy succeeded because of its deep roots in faith in the Almighty.

It seemed obvious to him that the new Japanese democracy needed the same firm foundation for success. In November of 1945, he welcomed four American clergymen, the first civilians to enter postwar Japan, to Tokyo’s Dai-Ichi Insurance Building. There he told them: “Japan is a spiritual vacuum. If you do not fill it with Christianity, it will be filled with communism.”

Helmets for pillows

The Western world in general agreed with MacArthur’s estimation that Japanese culture needed to change. Japan’s religious beliefs were ancient and strongly held. The traditions of Shintoism and Buddhism meshed with a long-standing culture that seemed to support the ideal of honorable suicide whether by hara-kiri or seppuku (self-disembowelment using a large sword) or kamikaze (suicide attacks during WWII using planes).

Order Christian History #121: Faith in the Foxholes in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

The first-person experiences of American soldiers only added to this opinion, with testimonials of Japanese brutality in the treatment of prisoners and eyewitness accounts of suicides in the name of the emperor. Although it was not published until 1957, Robert Leckie’s famous A Helmet for My Pillow typifies the stories told by many.

The Japanese military also believed that missionaries throughout Southeast Asia were spies (some, like John Birch, were; see “John Birch, fighting missionary,” p. 52) and therefore could be subjected to torture. In one type of torture, the interrogator placed a tube down the throat of the victim. His abdomen was subsequently filled with large amounts of water. Another soldier would then jump on the abdomen, rupturing the stomach and other internal organs, often leading to death.

MacArthur called for a thousand missionaries to be sent from the United States in an effort to spread Christianity. He wrote to the president of the Southern Baptist Convention in 1956, “Christianity now has an opportunity without counterpart in the Far East.” In 1949 MacArthur welcomed visitors from around the world in celebration of the 400th anniversary of St. Francis Xavier (1506–1552) arriving as a missionary to the island nation.

To fulfill MacArthur’s vision, Japan greatly needed Bibles. A collection and fund-raising drive began, and the goal of 10,000,000 Bibles was met. Japanese citizens readily accepted the Bibles—sometimes because they contained cheap paper that was useful in many ways. By 1950, 2,500 missionaries served in Japan.

MacArthur also saw education as a valuable means of leading the Japanese nation to Christ. He raised funds and served on the board of a new university specifically established as a Christian school, the International Christian University. It opened in 1953 in the Japanese city of Mitaka, near Tokyo.

MacArthur’s optimism peaked in the late 1940s, following evangelist doctor Toyohiko Kagawa’s 1946 appointment to Japan’s House of Peers and Christian socialist prime minister Tetsu Katayama’s election in 1947. Katayama appointed four Christians to his cabinet, and they completed a 427-day “Campaign for Christ” across Japan. But the rule of Katayama and his cabinet only lasted until February 1948.

Though MacArthur encouraged the spread of Christianity in Japan, he still stressed the importance of freedom of religion. He later told Billy Graham that the emperor was willing to make Japan a Christian nation, but he did not feel it right to mandate such a move.

At the height of Christian mission in Japan under MacArthur in 1951, Christians made up 4,000,000 of the nation’s 83,000,000 population. By comparison Shinto believers numbered 17,000,000, and Buddhists numbered 45,000,000. MacArthur did not fully understand the connection of these ancient religions to Japanese culture. He also did not fully comprehend the struggle of a missionary’s work. Today 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 Japanese identify as Christian, making up 1 percent of the population.

The church goes underground

Meanwhile a different challenge arose in the newly forming People’s Republic of China. Missionaries had arrived in China as early as 623; the first recorded missionary was a Persian man named Alopen, and European missionaries came in large numbers in the mid-1800s as the Opium Wars broke out.

Arguably the most famous missionary to China arrived in 1854, though. His name was James Hudson Taylor (1832–1905), the father of the China Inland Mission (CIM), now known as Overseas Missionary Fellowship (OMF) International.

Hudson Taylor’s organization has been credited with bringing 800 missionaries to China, resulting in over 18,000 conversions. His impact and legacy live on to this day. CIM remained active in China throughout World War II, but as Communism swallowed China, growing atheism and laws against churches and religious expression forced the church underground. It remains there today.

At the height of World War II, 4,000,000 Chinese people identified with Christ. Today estimates run as high as 100,000,000 believers in the underground church. Whether due to the many centuries missionaries were present in China, the volume of Westerners who lived there during the days of colonization, or the effects of persecution, the church in China thrives to this day in a way not true in Japan.

But in the days during and after WWII, CIM workers and those from other missionary organizations found themselves in precarious situations. CIM worker Phyllis Thompson, in her book China: The Reluctant Exodus (1979), related many harrowing experiences. One Swedish female missionary, E. E. Lenell, was tried and executed by a tribunal of the People’s Republic.

To Thompson’s knowledge this marked the first time a missionary had been put to death by the Chinese government. Many had lost their lives through war, from sickness, or from crime, but never before had a missionary been openly executed.

CIM officials, headquartered in Chinese Nationalist–held Shanghai, understood the realities of their team members serving in Communist-held regions. For a time an order of evacuation was given. In the end, however, CIM workers unanimously approved a policy of no evacuation in the areas overtaken by the Communists. Bishop Houghton, the general director of CIM China, stated, “We have yet to prove that Christian witness will be impossible under a Communist government in China.”

Blossoming under persecution

But the Chinese Communists continued to push south, winning battle after battle against the Chinese Nationalists, and eventually taking Beijing in 1949. The People’s Republic of China was proclaimed on October 1, 1949, and a new culture in China took hold, characterized by antireligious sentiment and the rejection of Western culture and thought. Government placed a new emphasis on Chinese culture and ideals.

The People’s Republic allowed traditional Chinese religious practices to continue as long as they met the strict standards of the government, but the squeeze against Christianity continued. Missionaries realized that the greatest risk of violence or imprisonment was toward Chinese natives who identified as Christian. As a result many missions began to leave the country. For a time CIM remained and even brought new missionaries to the field, but, as an OMF historian later wrote,

It eventually became plain that the continued presence of the missionaries was causing suspicion and harassment for the Chinese believers. In 1950, the momentous decision was made that, in the best interests of the Chinese church, the China Inland Mission (CIM) would withdraw.

CIM moved its East Asian headquarters to Singapore, and the Chinese church was left to grow on its own, which it did, surviving and even thriving.

People often assume that Christianity should thrive where freedom of religion is encouraged and suffer under persecution. In East Asia the opposite seemed to be true. One Chinese minister said during the Nationalist-Communist conflict, “Do not pray for our safety, rather pray that we can endure persecution.”

Whether MacArthur’s dreams for Japan will one day be realized, and whether the Chinese church will continue to grow under persecution, no one knows. But in the end, World War II played a significant part in spreading Christianity across the Orient. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #121 Faith in the Foxholes. Read it in context here!

By Darren Micah Lewis

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #121 in 2017]

Darren Micah Lewis is the lead pastor of Calvary Christian Center in Louisville, Kentucky, and the author of Captured by the Rising Sun: Missionary Experiences under Japanese Occupation, 1941–1945. For more on the underground Chinese church today, check out our issue 109, Eyewitnesses to the Modern Age of Persecution.Next articles

The problems of peace and the problems of war

Excerpts from two war sermons

Harry Emerson Fosdick; Edward TalbotMitsuo Fuchida: from Pearl Harbor attacker to Christian evangelist

What sparked Fuchida’s interest in Christianity?

Matt ForsterSpreading light in a dark world

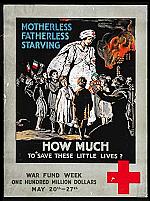

The world wars served as a pivotal time for Christian relief efforts

Jared S. Burkholder