Citizens of no mean cities

WHAT MAKES A CITY GREAT? A large population, an extensive territory, and an impressive organization are hallmarks of modern great cities. But, in the Roman Empire, what made a city was its legal status.

The term “city“ derives from the Latin civitas, a place whose members are citizens (polis in Greek) bound by a common law. In Acts 21:39, Paul identified himself as a polites of Tarsus, “no mean city” (as the KJV has it). In Acts 22:28 and other places, Paul claimed Roman citizenship by birth as well.

Great cities, few people

Ancient cities all had a forum with temples, a curia (hall of justice), an aqueduct, a theater, and other public buildings. They were small in comparison to their modern counterparts. One could walk down the long narrow roads from one end to the other in a day, even in the relatively large cities of late antiquity.

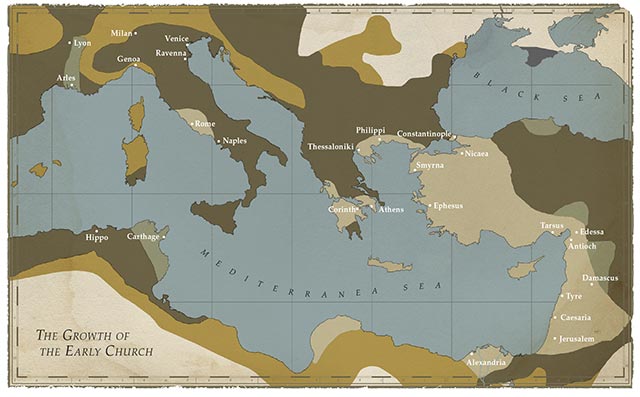

Christianity in the Roman Empire through Six Centuries. Doug Johnson

Residents were packed in, with little privacy. How easy it was to get food to the population determined the dimensions of a city. No ancient city exceeded a million inhabitants, even Rome. In fact if a city reached 100,000 inhabitants, it was called and considered great.

Scholars today agree that it is impossible to precisely determine the number of inhabitants of ancient cities. Since data records are spotty, scholars use interpretive models and make hypotheses and projections to estimate population. For all the vast physical spread of the Roman Empire, the entire population is thought to have been between 50 million and 120 million. (In the same area today live many hundreds of millions of people.)

The size of any given city population varied wildly, due to plagues, earthquakes, wars, and illness. Living in high-density housing, the lack of basic hygiene and medical care put poorer classes at the greatest risk of illness and death. The quality of their food was also lower, while the upper classes could afford a more varied and healthy diet.

Let’s visit a few of the empire’s famous cities in late antiquity and find out what they were really like.

ROME, city of immigrants

Step into Rome in the first or second century, and you’d find a great cosmopolitan and multi-ethnic capital of a vast centralized empire. Rome’s inhabitants were both Roman citizens and numerous peregrini (free people, but not Roman citizens) from all over the empire. Rich families had many slaves and ate lavishly, while the poor lived in crowded apartments and ate gruel.

If you were a Christian here in the first century, perhaps you would have been acquainted with Peter or Paul, the two apostles who died in the city. Or maybe you would have been among the first to hear Paul’s famous epistle to the Romans read aloud to your church community.

Evidence suggests that people lived in the area of Rome for over 10,000 years before Christ, but tradition claims the city itself was founded around 753 BC. The population during the early church era is best surmised from records of capita civium, adult male citizens. We have some reasonable records of the rich, who could afford tombs with inscriptions, and we know something of the poor, based on the numbers of people receiving free food from the city.

Based on all this, one of the best estimates is that the first-century population was around 600,000, decreasing at the time of the great epidemics at the end of the second century.

Citizens of Rome enjoyed better living conditions than their counterparts in the rest of the empire, resulting in a longer life expectancy; and women in the capital married at a young age, giving them more years to bear children. These two factors help explain the population growth of the city relative to others.

Immigrants further added to Rome’s growth in the first and second centuries. People from all over the Roman Empire, especially its eastern part, immigrated to Rome. They did not usually gain Roman citizenship, but they came anyway, often seeking jobs or better living conditions. Some even came from outside the empire’s borders.

Rome had been since its foundation a city of immigrants with an ongoing process of integration. Membership in ancient Roman society was not based on race, language, or culture, but on ius (the rights or laws that citizens were entitled to, the root of our modern word “justice”).

At the time of Constantine, inhabitants numbered between 700,000 and a million. This number diminished during the fourth century. The population regained steam again until the fifth century, followed by a final sharp decline when the Visigoth Alaric sacked Rome in 410.

The Christian community increased in the second and third centuries, and Rome’s bishop soon became the connection between Christian communities in the empire. Famous early Christians associated with Rome (besides Peter and Paul) include the first bishop of Rome, Clement (c. 35–99); theologian Hippolytus (170–235); and apologist Minucius Felix (died c. 250).

ALEXANDRIA, a center of culture

Those lucky enough to visit Alexandria in the first century would have been met by a cosmopolitan mix of Greeks, Romans, Jews, Egyptians, and Africans. By the second century, Christians too could be found in this eclectic city.

Alexander the Great founded this second-largest city in the empire on the Nile Delta in 332–331 BC. Its magnitude grew with rule by the Ptolemies, and it became the capital of Egypt, remaining so even after Rome conquered Egypt around 30 BC. The Roman period lasted until the arrival of the Arabs in the seventh century. It was the largest cultural center of the east, bigger than Athens and Antioch in Syria. In this context it was also an important cultural center first for the Jews and later for the Christians.

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Evidence on Alexandria’s size from literature, archaeological digs, and inscriptions is very scarce. Greek historian and geographer Strabo did visit Alexandria in 25 BC, offering us a list of public buildings. The Sicilian Diodorus (who died around 27 BC) recorded a figure of 300,000 people in 60 BC, making it a bit more than half the size of Rome. According to some scholars, Alexandria had no more than 500,000 to 600,000 inhabitants in the late fourth century.

Christianity grew quickly in Alexandria in the third century, and the city was a veritable hotbed of great theologians: Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–c. 215), Origen (185–254), Dionysius (d. 264), Athanasius (c. 296–373), and Didymus the Blind (c. 313–398). (For more on all of these, see our issue 105, Early African Christianity.) At the Council of Nicaea (325), the Alexandrian bishop’s seat was placed second after the Roman bishop’s.

ANTIOCH, the window to the east

Third in our tour of great cities is Syria’s Antioch on the Orontes River, founded in the year 300 BC. It was the capital of the Seleucid monarchy and also often served as an imperial residence. Here you might meet traders from all over the known world. With its easy river access, the city was a meeting point for ancient trade routes and was one of the two poles (with Edessa) of the Roman strategic system of defense. In fact you might glimpse emperors leaving from Antioch for wars to the east.

Antioch was also a cosmopolitan city where many people from the Middle East came for commercial and cultural reasons. The population was mainly Greek in culture and used Greek as the official language, but Syriac was also spoken, especially in the surrounding countryside. Here was a strong Jewish community, so Jesus’ followers arrived early. The believers in Antioch have the distinction of being the first to bear the name “Christians” (Acts 11:19–26). Paul set out from Antioch for his first missionary journey. Later it came to be considered one of the five great seats of the patriarchs.

Antioch often suffered major earthquakes, the most devastating in 115 and 526. Destruction also came in the form of attacks by the Persians (in 256) and by the Arabs (from the seventh century on). The ancient city is buried today beneath modern buildings and the sediments of the River Orontes.

Even in the fourth century, Antioch was called a “splendid and eminent city for public works.” It had fewer inhabitants than Alexandria, but it is not easy to offer any precise number, because very little information exists. Common estimates place the population at about 150,000. Ignatius

of Antioch (c. 35–c. 107) was one of its most famous early church fathers, and John Chrysostom (c. 349–407) was born and ordained there. He became a popular preacher in Antioch before being named archbishop of Constantinople.

CARTHAGE, vibrant faith community

Our next stop is Carthage, in Africa Proconsularis (modern Tunisia), near the city of Tunis. Here, in the empire’s fourth largest city, we find a thriving and vibrant Christian community.

Carthage was founded by the Phoenicians in the ninth century BC, destroyed by the Romans, then rebuilt by the two Caesars, Julius and Augustus. Its inhabitants were in close contact with Rome for study, trade, and cultural relations. The Arabs destroyed the city in 698.

Many archaeological remains have been preserved in Carthage, though in recent decades modern people have covered some of them with residential villas. Inscriptions also abound. The number of Carthage’s inhabitants might have reached about 100,000.

Born in Thagaste, Augustine (354–430) moved to Carthage at the age of 21 in 375 and lived there until 383, when he went on to Rome and then Milan. Carthage became the site of many of his youthful indiscretions. In Carthage he left Christianity for a time for Manichaeism, and he fell in love with the unnamed mother of his son Adeodatus. After his conversion Augustine returned to Carthage several times as a visiting preacher.

CONSTANTINOPLE, the “new Rome”

Finally we’ll cross back over the Mediterranean Sea to the city modeled after Rome itself: “New Rome,” Constantinople. Here you will discover magnificent historical monuments and works of art collected from all over the Greco-Roman empire (see “Christianity goes to town,” pp. 30–33). You will also find the first intentionally “Christian city” and marvel at the impressive Hagia Sophia and the Great Palace.

Emperor Constantine chose the ancient city of Byzantium in 324 as the new imperial seat, renaming it “City of Constantine” (Constantinopolis). Sometimes it was called simply “the city” (polis in Greek) for its excellence, and its name today, Istanbul, derives from the expression “to the city” (eis ten polin in Greek). Constantinople continued to expand, making a growth spurt that same century during the reign of Theodosius I.

After the fifth century, Rome’s population declined—in the year 600, Rome may have had only 100,000 people—and the population of Constantinople increased until it became the largest city of the Middle Ages, with 300,000 to 400,000 residents. For 11 centuries after Constantine made it his capital, it was the seat of the eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, and its bishop became the second in prominence after the pope, bishop of Rome.

The emperor built many places of worship at Constantinople, housing relics of martyrs and sacred objects as a way of acquiring new political and ecclesiastical prestige. Thus began the great rivalry between Constantinople and Rome.

Other stops on the tour

These were not the only important cities of late antiquity; others had large numbers of inhabitants and administrative, cultural, and religious importance. Traveling around the eastern Mediterranean, your tour could include Corinth, to whose church Paul addressed two letters; Smyrna, home of the early church martyr Polycarp (69–155); and Ephesus (in modern western Turkey), to whose church Paul also wrote and where a famed council convened in 431 to condemn Nestorianism.

Moving on you might stop at Edessa (in Mesopotamia), home of theologian Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306–373); Damascus (in modern Syria); and Caesarea (in Palestine), where Eusebius (c. 260–339), a pioneering Christian historian, was bishop. In the south of Mesopotamia, you could visit the twin cities of Seleucia-Ctesiphon on the Tigris, south of the later site of Baghdad and destroyed by Arab conquest in 637. Edessa and Seleucia-Ctesiphon (capital of the Sasanian kings) were the centers of Syriac and Persian Christianity.

Touring the Mediterranean cities of antiquity demonstrates that Paul was not the only citizen of no mean city. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #124 Faith in the City. Read it in context here!

By Angelo Di Berardino

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #124 in 2017]

Angelo Di Berardino is past president and current professor of patrology at the Augustinian Patristic Institute (Augustinianum) in Rome, author of the Historical Atlas of Early Christianity, and editor of the Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity.Next articles

“The transformative love of God in our lives”

Greg Forster is director of the Oikonomia Network at the Center for Transformational Churches, Trinity International University. These reflections on Christians and culture are adapted from a blog series at The Green Room.

Greg ForsterFaith in the city: Recommended resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you understand the early church as an urban movement.

the editorsUnusual character

The Epistle to Diognetus describes the extraordinary character of early Christians

Unknown