Cooperation for the gospel

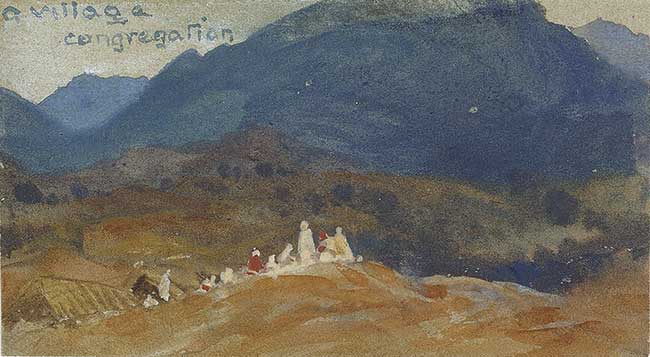

[Lilias Trotter, A Village Congregation in Egerton Journal, 1893—Used by permission of Lilias Trotter Legacy and Arab World Ministries of Pioneers]

North Africa nurtured many early theologians, councils, and important Christian writings. Figures such as Tertullian, Augustine, and Cyprian lived and worked in or near modern-day Algeria. But after the Arab invasions of North Africa in the seventh century, the church that had expanded there steadily eroded in Islam’s wake. For almost 1,200 years, the shores of North Africa were nearly untouched by any Christian missionary, though Ramon Llull (1232–c. 1315), a Mallorcan philosopher and apologist, journeyed to North Africa in the thirteenth century seeking to evangelize the Muslim population there.

Then, in the year 1830, France invaded Algeria, opening Muslim North Africa as a potential mission field for the first time in centuries. Missionary migrations often coincided with Western political expansion—which was not without controversy (see pp. 30–33). With access to Algeria opened, both Catholics and Protestants began entering the region.

In the early half of the nineteenth century (called by some the Great Missions Century), missionaries trickled into Algeria. Early attempts at sustained evangelism were short-lived or individual efforts, and others aimed primarily to minister to Europeans (this was the case with many Catholic missions). In the 1880s Protestant evangelical organizations began to go to Algeria. Many shared common visions and goals, leading them to cooperate.

The North Africa Mission (NAM) was the first of these organizations established in Algeria. Beginning as a small mission to the Kabyle people, it eventually spread out across all North Africa. George Pearse, an Englishman, went to Algeria in 1876 initially to evangelize French soldiers, but found the Kabyle receptive to the gospel. After others joined him, Pearse opened several mission stations by the end of the 1800s, primarily seeking to evangelize indigenous groups of North Africa such as the Kabyle and the Tuareg.

In addition to its evangelistic activity, NAM translated the New Testament into the Kabyle language. By 1901 NAM had 16 stations and 85 missionaries, 63 of whom were women. These missionaries ministered through home visits, medical care, distributing Bibles, and public preaching.

A new mission

Three smaller mission efforts entered Algeria around the same time in the mid-1880s, begun respectively by French Wesleyans, Seventh Day Adventists, and the Plymouth Brethren. In general these efforts remained limited in personnel and geographical scope for several years. By the time that Lilias Trotter arrived in Algiers, the North Africa Mission was still the only major established organization.

In 1888 three single women arrived in Algiers from England to begin what would become the Algiers Mission Band (AMB), one of the most influential missions to appear in the region. The leader of the trio, Trotter, had at first applied to serve with NAM but was denied for health reasons. Undeterred, she completed a little medical training and moved to Algiers with Blanche Haworth and Lucy Lewis; all three supported themselves initially through their personal means. Without sufficient language skills, the women could not hope to achieve their primary goal, sharing the gospel with North Africans, so their first task was to learn the local language. Then they began building relationships with Algerian women. Eventually they formed women’s groups for prayer and Bible study, and more missionaries began joining them. In 1891 the AMB’s first convert was baptized.

Self-governing and self-supporting

On Sundays the AMB held meetings for Algerian Christian converts and those interested in hearing more. The women taught new believers the Bible and leadership, seeking ultimately to birth a “self-governing and self-supporting” church. Eventually they established mission stations in several parts of Algeria, spanning from the Mediterranean to the mountains and the desert beyond.

The desire to see North Africans come to Christ eventually led Trotter to begin early on an itineration (traveling) ministry into the Sahara, particularly to visit the Sufi mystics (see pp. 30–33).

The AMB began official Bible translation/revision work as early as 1904. It formed a literature committee in 1914, and a large portion of Trotter’s work after this consisted of writing and translating books, tracts, and Scripture for North Africans. Renowned missionary Samuel Zwemer (see pp. 35–38) called her the “pioneer” of Christian literature for North Africa. In this work Trotter continued to use her gift of art. Nor did she merely translate English works into Arabic. Trotter aimed to write new, engaging literature that would be both beautiful and theologically accurate.

Working together on mission

Trotter’s group was officially incorporated as the Algiers Mission Band in 1907. As an organization the AMB required no official training and accepted missionaries from multiple countries and denominations. Structurally its leadership consisted of an executive council, a council of outlook (for vision-casting), and the literature committee. The AMB actively sought “to have fellowship and to cooperate with all other evangelical societies.”

Over the years other missionaries and groups worked alongside the AMB in close partnership. For example a Danish mission sent four women to work alongside the group; they functioned as members of the AMB but were financially supported by their Danish sending organization. In 1896 Frenchman Émile Rolland and his family moved to Algeria independently to share the gospel. Rolland began selling Bibles with help from missionaries of NAM. In 1903 the Rollands moved to Algiers and began to partner with Trotter and the AMB until 1908, when they established Mission Rolland to conduct independent work—a student home, a women’s craft center, and Algeria’s first school for girls.

Throughout its existence the AMB recruited both short-term and long-term missionaries, and the most full-time members it reached at one time was 34. Over the course of its existence, the AMB worked in Algeria and Tunisia, stretching into the Sahara and maintaining its base in Algeria. In 1964, long after Trotter’s death, the AMB officially merged with the North Africa Mission, which later joined what is today Arab World Ministries of Pioneers.

One of the most significant mission events during Trotter’s time with the AMB occurred almost by accident, when American delegates to the 1907 World’s Sunday School Convention in Rome stopped for a few hours in Algiers. Upon learning that these delegates wanted to know more about mission work being done in Algeria, Trotter and the other AMB missionaries put together a presentation about mission and life in Algeria, the people and the culture, and the needs of the mission work.

Though the American delegates were only with the AMB women for about an hour, this hour had lasting effects on North African Christianity. Some of the women delegates formed their own “Algerian Mission Band” as an American auxiliary to the AMB, which financially supported four British women missionaries to Algeria. From the experience the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States caught the vision for mission work in Algeria. In 1908 it sent its first missionaries to Algeria to begin what would become the most well-resourced and widespread mission in Algeria and Tunisia. Zwemer later estimated that the Methodist mission was the best-equipped organization thus far to tackle the North African mission field.

All of these organizations remained interconnected, and a significant number of individual missionaries worked with at least two of the different groups over their careers. Rolland received help from the missionaries with NAM and later worked with the AMB, and Trotter, though denied official partnership with NAM, still maintained a relationship with it after beginning her own mission. Mission Rolland and the AMB had a philosophy of cooperating with other evangelical groups, and NAM and the AMB were distinctly interdenominational in character. When the Methodist Episcopal Church opened its first mission among the Kabyle people, one missionary from NAM and one from the Plymouth Brethren offered to join the mission, allowing it to have trained and experienced missionaries from the start.

The AMB leads the way

From the day Trotter landed in Algeria, she wanted to see North Africans believe in Jesus Christ. Trotter and the AMB employed a wide variety of methods toward this end, including everything from direct ministries—prayer and Bible study meetings, evangelistic itineration, Communion services, and Bible translation—to more indirect means of serving people, such as training in handicrafts, providing care for children, and offering medical aid.

They also pioneered new approaches and philosophies of ministry: prioritizing the colloquial language in speaking, writing, and translating; recruiting short-term workers; and seeking to reach families through women and children. And they did not shy away from explaining the visions and dreams of Christ that the Algerians brought to them, fully believing in Christ’s ability to reveal his truth to people in such a way.

Before the AMB grew into a larger organization, Trotter was independent of any group and financially secure due to her family’s wealth and the wealth of her senior colleagues’ families. Because of this she did not feel the usual constraints of the particular organizational style, methods, or approaches of a denomination or even an established interdenominational mission. This left her free to develop her own insights into the work, to forge new paths of mission approach, and to try all sorts of innovative methods.

Missiologist Lisa Sinclair noted that

Trotter’s writings reveal wrestlings with the as-yet-unnamed [missiological] concepts of incarnational ministry, contextualization, and power encounter. She spearheaded the use of short-termers and was active in the philosophy and process of missionary recruitment and training.

Trotter also trained and nourished new believers for future leadership, used illustration to share the gospel, and focused on special ministry to women and children. Above all Trotter sought to minister to the people around her in a way that they would understand and welcome.

Trotter was a prolific writer throughout her life in Algeria, whether as an official ministry effort or not. Many of her works she also hand-illustrated, using her gift of painting and love of nature to illuminate their truths. She wrote innumerable letters to supporters, friends and family at home, and missionaries in other parts of the world.

Trotter kept a daily diary for the 40 years that she lived in Algeria and led the AMB, containing a wealth of knowledge about her own life as well as the AMB’s work. In addition to this substantial amount of unpublished writing, she wrote reams of mission literature: articles for missions journals, AMB circulars, evangelistic tracts, devotional works, and lengthier booklets for a variety of audiences. She even promoted Bible translation.

Total devotion

During the Great Missions Century, Lilias Trotter was one of the key figures in the collaborative mission network of Protestants in Algeria. Trotter’s life was one of total devotion to her Lord Jesus and complete surrender of all the world had to offer so that she could give everything she had for God. She showed this by giving her life, her mind, her art, and even her health for the sake of the gospel in North Africa.

At the end of the Great Century, some Algerians had become Christians, but still Algeria had no thriving indigenous church. But because of Trotter, individuals had been called to the mission field, entire groups and a major denomination began work in North Africa, countless North Africans read or heard the gospel, and countless more were touched by her love for them and for Jesus. Many followed Jesus due to her influence.

In the last years of her life, confined to bed, Trotter never stopped learning of her Lord’s ways. She wrote in her diary, “Long ago, in the past, it was a joy to think that God needed one. Now it is a far deeper joy to feel and see that He does not need one, that He has it all in hand.” May Christians today look upon her life and see that it was God who worked in and through her—and it is that same God who can also work in them. CH

By Rebecca C. Pate

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #148 in 2023]

Rebecca Pate received a master of theology with an emphasis in historical theology and an MA in intercultural studies from Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and is Southeastern’s director of marketing and communications.Next articles

God told her to go

Like Trotter, Amy Carmichael blazed her own missionary trail

Jennifer Woodruff TaitReaching the “Brotherhood men”

Trotter’s evangelization of Sufi Muslims fit within a larger context of Muslim-Christian relations

Edwin Woodruff TaitArtists, angels, apostles, and the abode of peace

Some of Trotter’s friends, colleagues, and mentors

Jennifer Boardman