Editor's note: Francis Asbury

They pray the most, they preach the best.

They labor most for endless rest;

I hope my Lord them will increase.

And fill the world with Methodist.

The world, the devil, and Tom Paine

Have tried their best but all’s in vain.

They can’t prevail, the reason’s this:

The Lord defends the Methodist.

(Methodist song, c. 1813)

I HAVE TRIED for much of my life to understand Methodists.

My youth was spent navigating the waters of United Methodism in the 1970s. By then it resembled the average American mainline denomination: large churches, multiple seminaries, settled long-term pastors, extensive music and youth programs, and an honored place in American political life.

It was not until I attended graduate school with the purpose of studying my own tradition that I truly realized that Methodism’s beginning in America was many things I had not expected: rowdy, ecstatic, sacramental, and unstoppable, spreading the Gospel in ways uniquely suited to a growing nation.

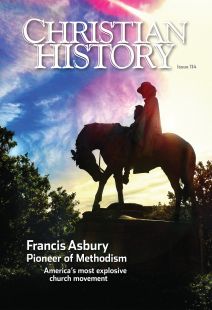

One of the major movers of that unstoppable force was Francis Asbury (1745–1816). This young Englishman, a metalworker by trade and son of a common laborer, heard the Methodist message in his teens and volunteered in his twenties to go as a Methodist missionary to the American colonies. A tireless and dedicated traveler, he became one of the most respected American Methodist preachers. When in 1784 a Methodist denomination separate from its British roots was formed in the new nation, Asbury was the obvious person to take charge. He was, after all, the only British-born Methodist preacher who had remained in the colonies during the Revolutionary War.

Encouraged by Asbury’s constant travels, early Methodists set out to evangelize the continent. Forged in small groups, encouraged by boisterous camp meetings, and singing its way across the nation to vigorous tunes, the movement spread like a sanctified brush fire.

As it grew, however, the fire was directed and controlled—perhaps even domesticated. Pastors who settled in large city churches replaced circuit-riding preachers. Outdoor worship moved inside to elegant Gothic churches with carpets, trained choirs, and pews rented to the well-to-do. Methodists gained access to powerful politicians and wealthy backers.

Still, the church maintained a reforming energy—especially through the temperance movement. Speeches, marches, writings, songs, and the labors of countless Methodists powered the fervor for total abstinence from alcohol that swept late nineteenth-century Protestantism. Even in my own childhood, Methodists clearly stood for the idea that, when faced with social problems, churches need to roll up their sleeves, wade in, and get to work.

While no longer United Methodist, I am still a historian of Methodism and have even published a book about why Methodists use grape juice in Communion. I also once worked at the United Methodist Archives Center (UMAC) in New Jersey, a cooperative venture between Drew University Library and the General Commission on Archives and History of the United Methodist Church. They have cooperated generously with time and images in the preparation of this issue.

So this issue’s story (and images!) are close to my heart. I hope you enjoy reading about Methodism’s ecstatic beginning and its country-conquering energy. And I hope its transition from frontier conflagration to respected cultural force raises for you some of the questions it always has raised for me—about what was gained, and about what was lost. CH

Jennifer Woodruff Tait

Managing editor, Christian History

In CH 113, Lilia MacDonald was misidentified as Lucy in “Did you know?,” Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson as Kirsten on p. 3, and Highbury College as High College on p. 24. Joe Ricke, professor of English at Taylor University, should have been credited with the description of Tolkien’s grave on p. 1. CH regrets the errors.

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #114 in 2015]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is the managing editor of Christian History.Next articles

Methodists and their stuff

Methodists have collected thousands of documents, objects, records, and artifacts

Christopher J. Anderson