Editor's note: The Catholic Reformation

AS THE ART STAFF and I were choosing the (amazing) pictures for this issue, we noticed a theme. Red. Lots of it. Mostly in the vestments of Catholic cardinals, whose stories thread through the following pages. Not every Catholic reformer was a cardinal, and not every cardinal was a reformer. But as we sorted through portraits and altar panels, sculptures and ceiling frescoes, I saw red, in a very good way: a tangible indicator of the vibrancy of the people and events we are unveiling.

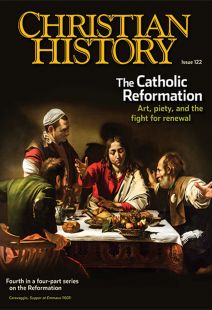

I’m deep in the sixteenth century by now, after three issues of our Reformation series, and this issue looks different from all the others. The Protestant Reformation had notably great artists: Lucas Cranach and Hans Holbein come to mind as giving us indelible images of nearly all major Protestant figures of the sixteenth century. But somehow the art for this issue is different: dramatic, rich in color and texture, and unabashedly emotional. Our cover illustration, Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus (1601), is a perfect example of a vibrant painting in this style with a fresh interpretation of the biblical narrative.

It turns out (as you’ll read shortly) that sixteenth-century Catholic art was this way on purpose. And it also turns out, for me, to be a good metaphor of how the issue struck me. Catholic reform was not merely a response to Luther’s dramatic moment, or to Zwingli’s fiery preaching, or to Calvin’s religious metropolis in Geneva. It was something that began before 1517 and something that went on throughout the sixteenth century, sometimes in response to Protestantism but sometimes almost in isolation from it.

Through the looking glass

The vibrant art was only a taste. As I immersed myself in the Catholic Reformation, I felt as though I had stepped through the looking glass. Here was the same century I thought I knew well, but with an entirely different cast of characters, an entirely different set of events, all seeking an answer to the same question that troubled Protestants: Something has gone wrong here—how can we fix it?

In service of that question, religious orders reformed and new ones emerged—not least the Jesuits, founded by the high-living soldier, Ignatius of Loyola, who turned from dueling to fighting for Jesus. In service of that question, Loyola’s Jesuits circled the globe. In service of that question, mystics and writers gave to their age, and to our own, timeless devotional classics seeking a life of prayer and union with God.

In service of that question, leaders formed reform commissions, dialogued with Protestants, rooted out heretics, and eventually convened the Council of Trent, which forged a uniquely Catholic way of reform. We tell all those stories here—as well as following the Protestant story to the seventeenth century, when it began to impinge upon the New World as well as the old.

If you, like me, are a Protestant, then reading this issue will require you, as it did me, to think differently about what reform looked like in the sixteenth century, where it happened, how, and why. But if we are to explore the vision expressed on p. 46 in our final round table—of healing these old wounds and cooperating in the Gospel’s spread—then we need to begin by hearing one another’s stories. Let this issue—and all its vibrant red—be a start. CH

Jennifer Woodruff Tait

Managing editor, Christian History

This article is from Christian History magazine #122 The Catholic Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #122 in 2017]

Next articles

Helping souls

How religious orders of the sixteenth century pursued reform and holiness

Katie M. BenjaminThe Council of Trent speaks

Twenty-fifth Session (December 3–4, 1563), “Concerning Regulars and Nuns”

Council of TrentIgnatius of Loyola speaks

“Contemplation to Attain Divine Love,” The Spiritual Exercises (1541)

Ignatius of Loyola