Faith divided

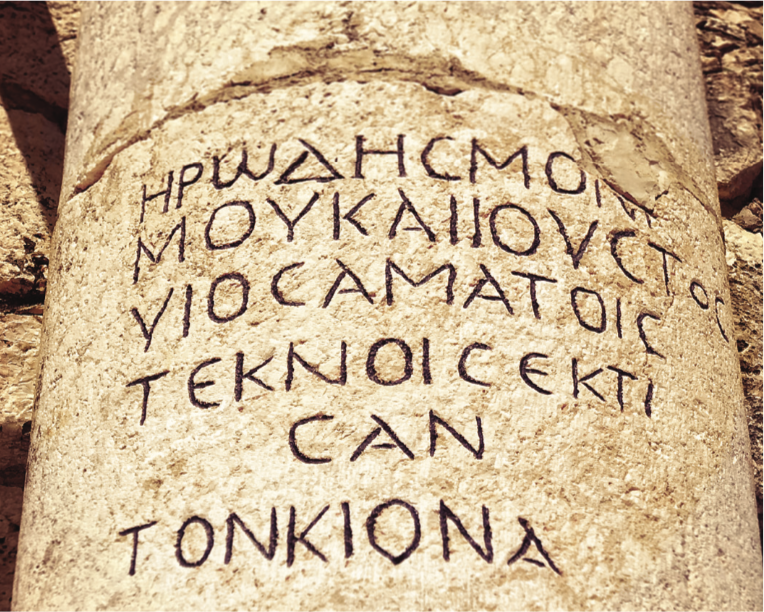

[Inscription in early synagogue, Capernaum, Israel, courtesy of Max Pointner]

“His blood be upon us and upon our children!” (Matt. 27:35)

When the author of Matthew committed those words to parchment two millennia ago, he had no idea how they would be grossly misused. The phrase was a standard Aramaic formula, an oath meaning “I commit myself to this decision.” Most legal battles or serious conflicts heard it uttered more than once. Yet less than a century later, Melito of Sardis (d. 180) wrote in an Easter sermon for baptismal candidates that every Jew was personally guilty of Christ’s death: “The Sovereign has been insulted. . . . God has been murdered; the King of Israel has been put to death by an Israelite right hand.”

Popes, patriarchs, and pastors echoed Melito’s words through the ages, as did lay Christians from learned princes to illiterate paupers. Within only a few generations of apostolic memory, followers of Jesus severed his Jewishness from him—even though he had preached the authority of Jewish Scriptures and the observance of Jewish law, commissioned Jewish followers and apostles, and died at the hand of pagan authorities.

Pagan backgrounds

Jew-hating was not a Christian invention. Jews lived alongside non-Jewish neighbors for many centuries before Christianity. Wars, mostly about who controlled land and resources, sprang up, as did peace, which prevailed but was rarely recorded. Political, military, and economic alliances were ever-shifting. The vast majority of Jews had significant acquaintances with non-Jews—friendly, hostile, or merely practical. Persians, Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians found Jews and their ways strange, but rarely stranger than they found one another’s or than Jews found theirs.

As small Jewish enclaves settled in the diaspora, places outside their ancestral homeland, and separated from the security and traditions of the larger community, they nevertheless maintained a unique imprint that intrigued their neighbors. They proclaimed that only one God existed and that, moreover, he should be worshiped because of his righteousness (tzedakah), loving kindness (chesed), and wisdom (hokmah), rather than simply because of his power.

People familiar with Egyptian and Greek modes of education might have been intrigued by synagogues where, instead of offering sacrifices, rabbis read and expounded canonical Scriptures—a unique religious practice in the ancient Mediterranean. In addition most Jewish communities had charitable schemes to keep members from destitution and enslavement. Greeks and Romans had no true equivalent; the presumption that contributions would come anonymously from all nondestitute members, as opposed to wealthy donors seeking public recognition, was new to them.

Some chose to convert. We do not know how many, but Philo of Alexandria, Josephus, and the Mishnah (see p. 11) speak about gentile converts to Judaism as a matter of course. Jews named these people who lacked Jewish ancestry but practiced the Jewish faith “God-fearers.” The New Testament records debate over whether these people should be considered Jews or gentiles, as well as whether gentiles who wanted to become Jesus-followers needed to become Jewish.

Massacres and Desecrations

But outside interest in Judaism could be sinister as well as friendly. The first independently recorded pogrom—an organized massacre of Jews, tolerated or even approved by authorities—took place in the Greco-Egyptian metropolis of Alexandria in 38 BC. A significant Jewish community had lived peacefully alongside other residents for centuries; only 200 years earlier, a complete Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, the Septuagint, had been produced there. The pogrom resulted in significant loss of life, as well as destruction of property and civil disorder. Authorities eventually intervened.

Though shocking, the Alexandria pogrom was not unprecedented. The idea of a ruler persecuting diaspora Jews in his kingdom and of a massive threat to Jewish minority communities resonated as far back as the book of Esther centuries before, which recorded the effort of Haman, a wicked Persian official, to kill every Jewish man, woman, and child in the kingdom. The queen, Esther, and her uncle and guardian, Mordecai, were able to intercede before King Ahasuerus only because they had long hidden their Jewish identity.

One of the best examples of such hostile outside interest occurred in the second century BC, when conquering Seleucid Greek ruler Antiochus Epiphanes IV desecrated the Jerusalem temple in a shocking departure from normal practice (most pagan conquerors wanted to keep the gods of conquered territories on their side, not offend them).

The books of First through Fourth Maccabees report that Antiochus and other Seleucid rulers banned circumcision, forced Jews to eat pork, and favored Jews who abandoned their own traditions and practices for Greek culture and language. Maccabees highlights faithful Jewish men and women, old and young alike, who chose to die rather than capitulate to the Seleucids’ demands, and eventually overthrew them. They lived on in the memory of communities wary of systematic persecution.

The Maccabeans proved better fighters than rulers. Their successors, the Hasmoneans, publicly converted to Judaism so their Roman backers could be seen installing “local” rulers, but Jewish subjects saw through this facade. The Sadducees offered their stalwart support, however, and in return, received control of the Jerusalem temple. Many factions opposed the Sadducees, including Essenes, Zealots, and Pharisees. Most Jews did not belong to any of these schools; but the Pharisees, who proclaimed the resurrection of the dead and the spirit over the letter of the Law, held the most mainstream position by far. In such an environment, religious teachers from outside the establishment, like John the Baptist and Jesus, were common. They gained followers, disciples, opponents, admirers, and critics.

Grafted in

The Gospels record interactions between these groups: such religious discussions, not always on the friendliest terms, were not surprising in the first-century world. However, most of the New Testament gives little sense of being about a religion outside Judaism. The word “Christian” appears only three times (Acts 11:26, 26:28, and 1 Peter 4:16), and Paul writes of gentile Jesus-believers as being “grafted” onto the Jewish olive tree, probably alluding to a metaphor for Torah. He speaks of only the one tree, ever-growing and true. If it is able to be supplanted, so is every tree that might be put in its place.

Yet by the time Pliny the Younger encountered the novel phenomenon of Christianity as the governor of eastern Turkey in the 110s, he seemed to have no idea that it had any substantive connection to Judaism. The disconnect reflects a complicated untangling hardly complete by Pliny’s time. Well into the fifth century, it could be difficult to tell whether a religious congregation in the eastern Roman Empire was a Christian church (Greek ekklesia, “assembly”) or a Jewish synagogue (Greek synagogue, “gathering-together”). The celebrated preacher John Chrysostom, hostile to Jews and frustrated that many of his congregants were not (see p. 16), with exasperation finally told would-be worshipers simply to ask which faith the congregation followed.

Some Jews clearly did persecute Jesus-followers during the earliest period, but the majority did not. And while some Christian leaders and believers hated Judaism, most did not—if they even encountered it. Most Christians in the northern and western Roman Empire rarely did. After Constantine’s conversion some Christian lawmakers and laypeople took the next step toward legal sanctions and in-person persecution of Jews. They were distinctly in the minority, but they laid the foundation for much hostility to come.

The temple falls

In AD 70 the Roman army destroyed the Second Temple, along with much of the city, after a four-year-long Jewish revolt against Roman rule in the province of Judea. Such drastic action came as a shock: Romans, like the Seleucids before them, typically respected the religious sites of conquered territories, not wanting to anger gods who held power in that place.

The destruction of Jerusalem’s temple was especially devastating because it was the only place where Jews could offer sacrifices (synagogues were for prayer and study). And Romans understood sacrifice; it was the centerpiece of ancient Mediterranean worship. But the God of Israel, from the Roman view, was strangely singular in his demands.

Jewish and gentile Jesus-followers, and Jews who were not Jesus-followers, all felt the loss of the temple acutely. Acts and the letters of Paul indicate that Jesus-followers in Israel participated in temple worship; they also make it clear that even gentile Christians living elsewhere considered it important to make regular financial contributions to its operation. Both Jews and Christians needed to make a theological response to the temple’s loss, especially because temple sacrifices were sacrifices of atonement. Eventually Jews articulated the idea that good works and humble devotion are better than sacrifice and that God had allowed the temple to fall because he no longer encouraged sacrifice. Christians posited that Jesus’s death was the perfect atoning sacrifice and none further was needed.

This theological distinction between Jews and Christians might have been less important in another historical setting. But after the Jewish War (66–70), progressively more disastrous uprisings followed: the Kitos War of 115–117 and the Bar Kochba revolt 20 years later. After each conflict Rome leveled punitive taxes and other restrictions on Jews, regardless of whether they had supported the revolts (many had not). Non-Jewish Christians now had reason to avoid calling attention to their relationship with this potentially seditious sect, while non-Christian Jews had increasing incentive to distance themselves from another suspect religious group.

And Roman rulers were stepping up demands that people prove Roman allegiance by offering incense or libations to deified emperors. Most “deviants” could placate authorities without violating their own religious precepts. Jews could not, but were usually exempted because their refusal to sacrifice was seen as a hallowed ancestral practice rather than a dangerous innovation. Some Christians resented this exemption. Furthermore martyrdoms of Jews tended to be geographically confined to Judea and concentrated around political unrest there, diminishing by the late 100s. Martyrdoms of Christians, in contrast, were geographically widespread, varied, and came in unpredictable waves.

Over the course of the third century, Jews in the empire faced routine financial and some civic disadvantages but—if they were seen to “behave”—were largely ignored by an empire that had bigger fish to fry and more efficient scapegoats to target. During this same period, most Christian prospects turned on a dime. They could go about their ordinary business until, suddenly, a new provincial administrator decided they were the problem, or a natural disaster left the community looking for someone to blame, or a business associate developed a grudge. What happened next was rarely good. Martyrs, as Augustine noted, were much easier to admire than to emulate.

“Against the Jews”

Even in cities with major Jewish communities, pagans made up the vast majority of an average Christian’s non-Christian acquaintances and an average Jew’s non-Jewish ones. But they could not ignore each other entirely. Anti-Jewish theologies began to develop in Christianity before Constantine, although they do not seem to have been widespread. Jews were not universally upstanding about their religious differences with Christians either, but the course of history would not leave the two on an equal footing.

While racially and politically based anti-Semitism would not emerge until much later, two major categories of Christian anti-Judaism arose. The first category might be called simple hostility, reflected in the adversus Ioudaeos literature that began in the second century: argumentative texts putatively addressed to Jews but actually meant to unify Christians by establishing a common enemy, such as Justin Martyr’s “Dialogue with Trypho” and Tertullian’s and later Chrysostom’s Against the Jews. These texts used the Greco-Roman rhetorical technique of identifying an opponent and then arguing against a caricature of the opponent’s view. Literature of this type often slandered its targets as vulgar, womanish, servile, and otherwise lacking in character according to the customs of the Greco-Roman elite.

The second, more insidious element of early Christian anti-Judaism was supercessionism, the idea that the Gospels, the new covenant, and Christians respectively replaced Torah, the Mosaic covenant, and the Jewish people—this despite Paul’s reiterations of the goodness and eternal validity of God’s covenant with Israel and his explicit proclamation that “all Israel will be saved” (Rom. 11:26). Many declared that because Jesus is God’s anointed (Greek christos; Hebrew messhiach), God’s capacity to anoint had been exhausted, with the implication that, because Messianic promises applied to Jesus, they were of no further use.

As Christianity became favored and then official, a few Christians proved willing to use their newfound status and resources to persecute heretics, pagans, and occasionally Jews. In 388 a mob led by local clergy and their bishop destroyed a synagogue at Callinicum (in modern Syria). Emperor Theodosius commanded that the bishop should help rebuild the synagogue—to which Ambrose, bishop of Milan, responded in anger: “Shall the patrimony, which by the favor of Christ has been gained for Christians, be transferred to the treasuries of unbelievers? . . . It is the burning of a synagogue, a home of unbelief, a house of impiety, a receptacle of folly, which God Himself has condemned.”

Ambrose did not explicitly blame Jews for the death of Christ in his letter, though he did argue from Jeremiah 7:14 that God had rejected the Jews and had forbidden anyone from praying for them. But in the centuries to come, such rhetoric would take a deadlier turn. C H

By Eliza Rosenberg

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #133 in 2020]

Eliza Rosenberg is a postdoctoral teaching fellow in world religions at Utah State University.Next articles

Pictures of Jews in the New Testament

How some of the authors of the New Testament treated Jews in their writings.

Eliza Rosenberg