Faithful friar or scientific sorcerer?

[Bacon, Perspectiva, (1614). Public Domain—Images courtesy History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries]

In July of 1266, Roger Bacon (c. 1219–c. 1292) found himself in an awkward position. He and the current pope, Clement IV, had known each other for years, going back to the late 1250s when Clement had been a papal legate and Bacon himself had recently joined the Franciscan Order. In those earlier days, the two had shared conversations about the state of the world.

Both were of an ascetic bent. Both believed that Christendom’s internal conflict and Middle Eastern threats signaled the end times. Drawing on those conversations, Bacon now promised the pope a diagnosis of the age’s problems—and solutions to combat them. Clement IV swiftly wrote back, requesting Bacon’s insights and freeing him from any conflicting obligations to his Franciscan superiors. The response sent Bacon into a brief panic: he had not yet developed the proposed work!

Moreover, although he had spent years writing and teaching as a master of philosophy at Oxford and Paris, he had written little since joining the Franciscans in 1256. His position was further complicated by financial considerations; his family could not support him, having lost its wealth in Henry III’s expensive civil war with England’s barons. Yet this unpromising start led to a prophetic work of natural science: the Opus maius, a “greater work” in seven parts that sketched out his plan of reform. (Later installments, an Opus minor and an Opus tertium, filled in the details.)

Complete wisdom

Bacon began with the causes of error in society—people were ready to believe too much without good evidence—and then offered a way forward to what he called “complete wisdom.” Philosophy would have to be reformed. Universities should begin by teaching Greek and Hebrew and then the branches of mathematics before presenting a study of nature—or as Bacon called it, “experimental science” (scientia experimentalis). Teaching philosophy this way would supply theologians a moral foundation for healing Christendom.

Early fans of Bacon obscured his actual achievement. Medieval alchemists attached his name to their writings, ascribing a body of treatises to him. Renaissance thinkers described him as a magus or sorcerer using alchemy and astrology to uncover and manipulate the secrets of nature. Playwright Robert Greene (1558–1592) popularized legends of Bacon as a renegade monk using demonic magic to animate a talking brass head.

In early modern Protestant England, many downplayed Bacon’s Franciscan vocation and focused instead on his technological prowess. This was so in the Royal Society of London, the group of “new philosophers,” including Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton, who helped forge experimental techniques into new, coherent philosophies of nature. It became even more true in Victorian England, where proscience, anti-Catholic Protestants assumed Bacon could not have been both a devoted Catholic and an influential scientist. They were wrong: Bacon had seen his experimental science as a force for good capable of helping humanity out of its ignorance and toward a better future. But he did so because of his Franciscan commitments, not despite them.

Bacon’s vision of science looks modern in startling ways. He was committed to innovation, preferred experience over authority, and above all saw science’s value for society as lying in its technological utility. Even Bacon’s temper and style appears modern; he readily lambasted his opponents or those he thought intellectually dim. While commending the accomplishments of Aristotle and the lost knowledge of the ancients, he urged his contemporaries to improve on them. He repeatedly criticized translations and argued that Hebrew, Greek, Arabic, and even Latin should be subjects of sustained study—so scholars could amend bad manuscripts and clear up conflicting interpretations of the Bible and of ancient philosophers.

Calculating Easter

More than any other medieval intellectual, Bacon also recommended mathematics and disciplines using mathematical reasoning—optics and perspective, cartography, astronomy—as the sharpest tools for thought. He dedicated his longest section of the Opus maius to mathematics, calling it the “gate and key” to all knowledge, and expanded on its use in medieval theology: the computation of church calendar dates like Easter, the use of astronomy to understand eclipses (such as the one supposed to have occurred during Christ’s Passion), and geometrical and arithmetical pictures of the Trinity.

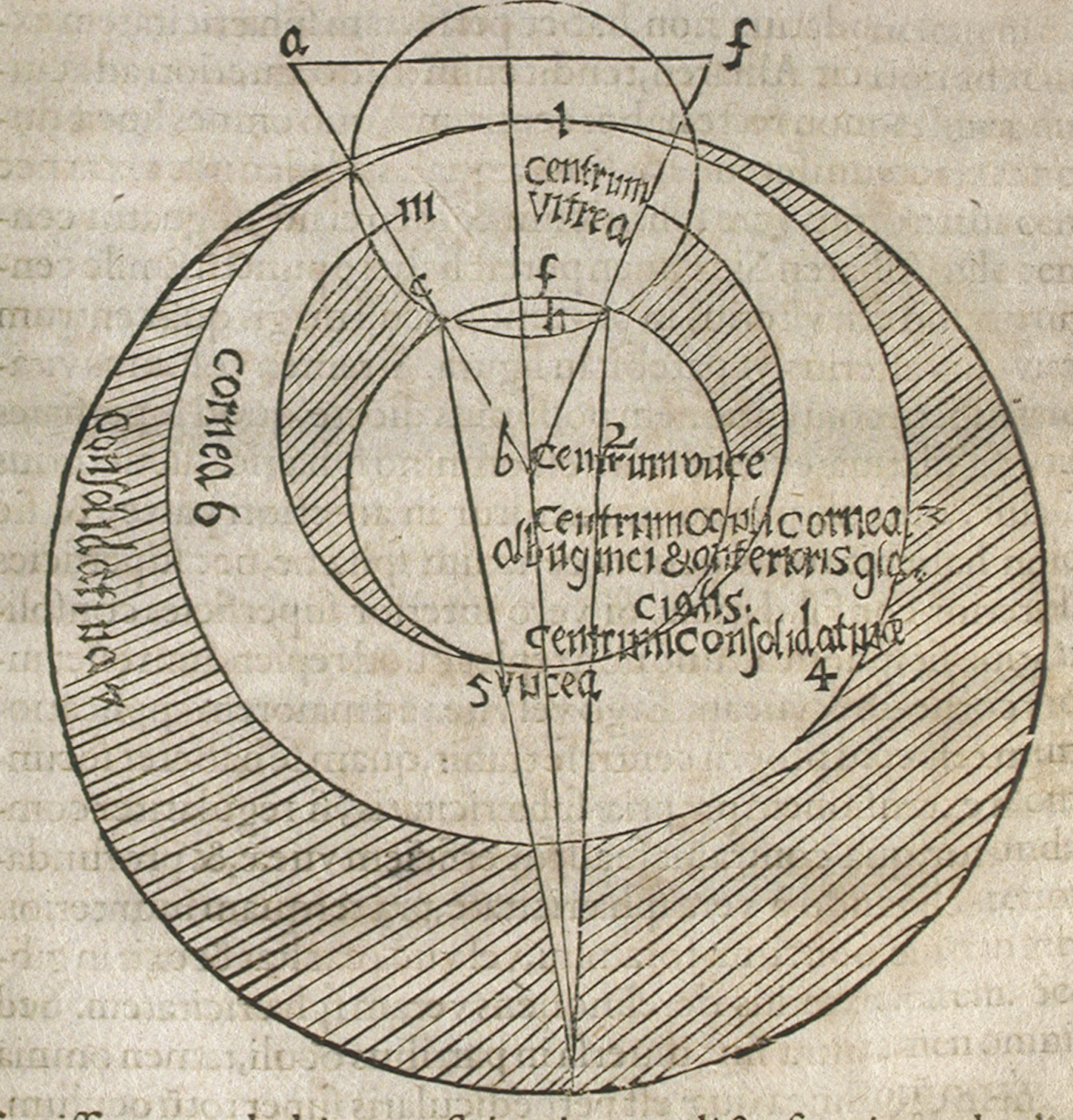

Bacon fastened upon light and sight as an example of how mathematical entities infused all of nature—the “science of rays,” or perspective. This idea was so important to Bacon that he sent Clement IV an additional treatise expanding on it. On the Multiplication of Species argues that all change in the natural world happens through “species,” a force or power by which one object acts on another. Bacon used this to explain light bending when it hits glass or water or a mirror, and vision when the image of something moves through the eye’s pupil to the optic nerve.

Bacon partly owed this “light metaphysics,” as some historians have called it, to Robert Grosseteste (see p. 18), whom Bacon had admired and probably read at Oxford. Grosseteste had written widely on optical subjects and reflected carefully on how to use experience in specific cases to understand more than mere intuition can—untangling complex truths that mingle mathematical and physical phenomena. Bacon added one ingredient more, thanks to his reading of scholars such as Arabic perspectivist Hasan Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen): using experiments not merely to uncover new truths, but to test knowledge systematically.

Bacon encouraged a hands-on approach to nature and claimed to have spent a small fortune of over £2,000 on language study, books, instruments, and materials. His writings on perspective describe many experiments with pinholes, lenses, or materials such as “crystals” for separating a rainbow’s rays. But to isolate all these marks of a scientia experimentalis from the purposes Bacon intended for his method misrepresents him.

Bacon’s larger concern was for the future of Christendom. Grosseteste shared this concern; in 1250 he had gained an audience with Pope Innocent IV and used the occasion to warn the papal court that its neglect of pastoral care was at the root of current wars throughout Europe, the threats of Mongols and Turks, the loss of Jerusalem, and especially the discontent and self-serving ambition of Christians. Depravity flowed from the “head” out to the body of the church in its dioceses. The only answer could be reform of the clergy. But how?

Universities, new institutions in the early 1200s, had supplied growing cities and courts with secretaries and bureaucrats, specialist lawyers, physicians, and theologians. The new mendicant orders, Dominicans and Franciscans, had set up study centers within universities so that their fast-growing memberships straddled ecclesiastical and secular lines of learning.

Only students with the stomach for completing the philosophy degree could study law, medicine, or theology. Previous papal restrictions on new translations of Aristotle relaxed, and new translations of Arabic commentators also circulated. Philosophical study became more sophisticated and standardized around new handbooks on Aristotle’s logic. Masters measured student progress in verbal examinations, called disputations; these public events drew crowds to witness logical swordplay.

Frustration with flaws developing in this system ran through Bacon’s advice. Bacon took a conservative view of the system, drawing on the ideal of the universities of his youth, when they seemed more clearly motivated by the Augustinian search for wisdom. The first book of the Opus maius argues that wisdom had become blocked by widespread error and ignorance, rooted in the pride of so-called scholars who accepted any authority simply because it was ancient or fashionable. The second book urges a return to the main goal of philosophy: to know the Creator from the created things.

Fall, apocalypse, technology

Another of Bacon’s driving assumptions was similarly widespread: that God had given Adam an original knowledge, much of which had been lost in the Fall, only glimpsed by ancients from Solomon to Aristotle, and corrupted through human institutions and history. The loss could be balanced and restored, however, by Christ’s first and second comings.

Bacon’s views of knowledge took on special intensity in the context of thirteenth-century debates over reform. Medieval religious orders had generally been founded to seek the state of grace of the primitive church, and the Franciscans were no exception. The followers of Francis of Assisi emphasized the spiritual value of ordinary and unlearned people; they stressed their founder’s simplicity, setting him alongside the ancient church’s hermits and apostles, fishermen and carpenters—like Christ. Franciscan debates over how to interpret Francis’s example reached fever pitch in the 1250s, during Bacon’s first years in the order. These debates focused on poverty: teaching, study, and travel required money, even for mendicants.

For Bacon, though, the idea of “original knowledge” showed that learning could revive this early perfection, and it could do so through experiment. Rather than webs of corrupting hearsay, designed to tickle ears but hide the truth, he proclaimed that touching, tasting, and seeing were the ways to understand the manner in which God had set the world’s foundations in place. Apostolic simplicity cut two ways. It countered selfish, greedy clergy and monks who used logic and authority only to compound ignorance. And for Bacon it suggested that lowly handcraft and experience could improve knowledge. The last shall be first.

Deepest ills

Such concerns grew even more acute due to a widespread sense that Christendom had come to a turning point in history. European Christians were killing one another, proving that the last days had come. The more rigorous wing of Franciscans turned to Daniel and Revelation to calculate various chronologies culminating in the appearance of the Antichrist—who was variously identified with the Mongols, Muslims, or a particular king or pope. Emperor Frederick II joined in the calculations, as did several popes.

Thus Bacon’s science was bound up with an evangelism designed to bring in the final number of the saved. Bacon believed right knowledge helps to diagnose sources of error, identifying what stops people from believing the truth. Unbelief could be countered with better proofs for faith. Moreover, better knowledge of geography and world affairs would equip the Latin West to anticipate and defend against the onslaught of the Antichrist’s armies.

The Opus maius suggests that alchemical wisdom would supply gold to fund armies and could devise large-scale weapons: diseases that spread through contact and might destroy an enemy without an army, or explosions of fire that burned even in water, or mirrors that could confound an enemy at a distance, or even incantations that might bring down heavenly power on an enemy’s head. Many came from the Secret of Secrets, an advice manual for princes translated from the Arabic tradition, and these earned Bacon much of his later reputation as a conjuror.

Like most ancient and medieval thinkers, Bacon also believed that environment—such as food and weather—affects health, body, and mind, and that the sun and other planets differently influence people in different places around the world. Heavenly powers therefore might shape human dispositions—including belief in particular truths. Within this framework Bacon advised the use of astrology to identify the distinctive natures of different peoples. Through it Christians would best learn how to persuade the nations of Christian truth.

In this distant setting it is easy to miss Bacon’s ideas that remain foundational assumptions in our own world, such as the promise of technology to help us address humanity’s deepest ills. Apocalyptic times allowed Bacon to give a vision of technology not merely as a conservative return to primordial wisdom, but a story of improvement, a progressive history. This assumption has underwritten some of the most ambitious projects of modernity—from eugenics to space exploration. Bacon might have been shocked to find himself sharing such ground. CH

By Richard Oosterhoff

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #134 in 2020]

Richard Oosterhoff is lecturer in early-modern history at the University of Edinburgh and author of Making Mathematical Culture.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: Faith and Science

A few of the highlights of Christian exploration of science that we touch on in this issue

the editorsThe clergy behind science as we know it

Enlightenment-era pastors didn’t oppose modern science. They helped advance it.

Jennifer Powell McNuttA world of love and light

Christian theology shaped modern science through the work of Johannes Kepler and Robert Boyle

Edward B. Davis