When God appears

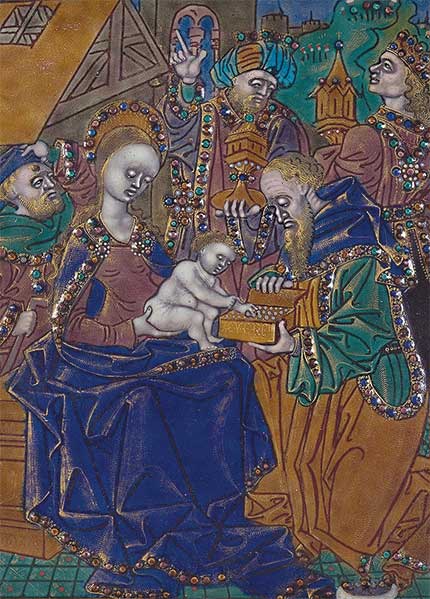

[ABOVE: Master of the Orléans Triptych, Triptych: Circumcision, Epiphany, Nativity, c. 1490. Enamel and Copper, France—Indianapolis Museum of Art / Public domain, Wikimedia]

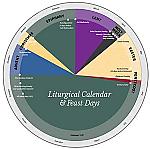

Epiphany (called more often “Theophany” in the Eastern tradition, which means “manifestation of God”) is one of the oldest feast days in the Christian tradition and the oldest part of the church’s temporal cycle (see p. 2) that is not explicitly part of the Lent-Easter cycle. The Sundays between the Feast of the Epiphany and Ash Wednesday continue the emphases of the feast itself.

Where did it come from?

No one is entirely sure, but we know Christians were celebrating this day as a unified feast—focusing on Christ’s birth, visitation by the Magi, baptism, and the first miracle at Cana—by the fourth century. It probably originated among Egyptian Christians. Clement of Alexandria (150–c. 215) made the earliest reference c. 200 to some kind of commemoration of Christ’s baptism around this time of year, and Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (330–c. 395) made the first written mention of the day in 361.

The settling of the date on January 6 may be due to an old tradition that Christ both was conceived and died on April 6 (we’ve already run into the way that this belief about another date, March 25, solidified the date of Christmas). For some time and in some places the church considered Epiphany the beginning of the church year.

How is the date determined?

Since its first celebration, Epiphany has always been on January 6. The number of Sundays after Epiphany (sometimes known in the West as Epiphanytide) varies depending on when Ash Wednesday occurs. The fewest possible number of Sundays is four and the most is nine.

Theological themes

In the East the observance of Theophany retains more of the unified character that the feast had at the beginning. It focuses chiefly on Jesus’s manifestation as divine through his baptism and the miracle at Cana, and only secondarily on the Magi. One congregation speaks of the feast this way: “Theophany in the Eastern churches is associated with spiritual enlightenment, renewal of all creation, and most importantly, the sanctification of the Jordan water.”

The West focuses mainly on the Magi on January 6, while the baptism of the Lord and the wedding at Cana are celebrated on subsequent Sundays during the season. What all these stories have in common is the glory of the incarnate Christ becoming manifest to the world—as a light to the Gentiles (as represented by the definitely non-Jewish Magi), through the descent of the Spirit at his baptism, and in the course of his very first miracle.

The readings for the Sundays after Epiphany normally focus on the mighty signs and acts of Jesus throughout the gospel story and emphasize the proclamation of the gospel message. In some churches, these weeks will be referred to as “Ordinary Time”—we’ll talk more about that concept later when we get to the Sundays after Pentecost, but it is not meant to imply that these Sundays are any less spectacular than other Sundays. The term comes from the word “ordinal,” which has to do with the idea of counting—in this case, counting the Sundays between the day of Epiphany and Ash Wednesday.

In many Protestant liturgical churches, the Feast of the Transfiguration—one of the most dramatic manifestations of Jesus’s glory—is celebrated on the final Sunday of Epiphanytide. (Roman Catholics and Orthodox celebrate the Transfiguration on its older date of August 6.) A famous hymn for the Transfiguration by Thomas Troeger (1945–2022), “Swiftly Pass the Clouds of Glory,” makes the connection between that event and the upcoming Lenten season and the path to the cross:

Glimpsed and gone the revelation,

They [i.e., Peter, James, and John] shall gain and keep its truth,

Not by building on the mountain

Any shrine or sacred booth,

But by following the Savior

Through the valley to the cross

And by testing faith’s resilience

Through betrayal, pain, and loss.

As the Christmas season’s endpoint, Epiphany sends us into the world to live out the Incarnation, to witness to the light of Christ in the darkness. Following Jesus we have been baptized into his death and Resurrection. Whether we are called to martyrdom, or to prophetic witness, or simply to faithful living in the joys and sorrows of our daily lives, we live all our days in the knowledge of our dignity, redeemed through Christ and united to God.

Colors

In Western churches white is used for the Feast of the Epiphany itself and, for those churches that celebrate the last Sunday of the season as the Transfiguration, for that feast as well. Green, the color for Ordinary Time, is used for the other Sundays. In the East, gold is used throughout (the Orthodox tradition normally uses gold when no other color is specified—the equivalent of Ordinary Time in the West).

Customs

Epiphany customs vary from country to country and, like Christmas customs, many have become deeply embedded as cultural as well as spiritual practices. In the West one common custom is “chalking the door”; families use chalk, often blessed by a priest, to write the traditional initials of the Magi and the current year on their house door (for Epiphany 2026, this would be written 20 = C = M = B = 26). Many liturgical Western Christians perform baptisms chiefly on four feast days during the year, one of which is the Sunday honoring the baptism of the Lord.

Another practice that frequently takes places in homes or at church gatherings on Epiphany, and then again on the last day of the season, is eating a “king cake”—a sweet pastry covered with icing and containing a plastic baby. Whoever gets the baby may win a prize and be considered king or queen for the day. Although it has older roots in the “Lord of Misrule” customs (pp. 14–15), as currently practiced, this custom mainly dates from the nineteenth century. In church on the day of Epiphany or on the Sunday immediately following, hymns honoring the Magi are sung and, if there is a creche, figures of the three kings are added.

Shrove Tuesday is the final day of the Epiphany season in the West, and it often features—in addition to more king cakes—pancake suppers where rich food, particularly meat and dairy products, are consumed, theoretically to use them up in preparation for the Lenten fast. The word “shrove” is the past tense of “shrive,” which means to forgive someone after hearing their confession; from about the year 1000 on, we hear of people making a thorough confession of their sins during the week before Ash Wednesday. Some churches ring bells on this day and burn palms from the previous year’s Palm Sunday to make the ashes for Ash Wednesday. The day is also called Fat Tuesday or Mardi Gras (which is “Fat Tuesday” in French), and in some places—most famously New Orleans and Rio de Janeiro—it has become an immense cultural carnival.

In Eastern churches Jesus’s baptism tends to be the primary theme of the day and, to some extent, the season. On the day itself, a Great Blessing of the Water takes place and the story of Jesus’s baptism is told. The priest also blesses the congregation, who are invited to take the blessed water home and consume it reverently; they may use it to bless their own homes or invite the priest to bless the home. In Bucharest children leading lambs walk through the subway trains to commemorate the Lamb of God to whom John pointed.

Nowhere is Epiphany celebrated more joyously than in Ethiopia. Pilgrims from all over the country converge on the ancient city of Aksum, where they bathe in a great reservoir whose waters have been blessed by a priest. Eastern churches do not celebrate Ash Wednesday, but end their Epiphany seasons on whatever Sunday is seven weeks before the date of Easter. CH

Some things to do at home

• Chalk your door and eat a king cake on the day of Epiphany and again on Shrove Tuesday! (If baking is not your thing, you can find king cakes in many grocery stores.) Pancakes are a traditional food for Shrove Tuesday.

• Epiphany is also a great day and season for house blessings, for the many reasons mentioned.

(This section incorporates text from CH #103, “The Real Twelve Days of Christmas” by Edwin and Jennifer Woodruff Tait.)

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #156+ in 2025]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is Senior Editor of CH magazineNext articles

Ash Wednesday

Believers are commanded to observe the beginning of Lent with repentance and prayer.

Jennifer Woodruff TaitForty days in the desert

Lent is a time of preparation for the celebration of Jesus’s Resurrection and the Easter feast.

Jennifer Woodruff TaitThe holiest week of the year

The week between Palm Sunday and Easter has traditionally been considered the holiest week of the church year.

Jennifer Woodruff Tait