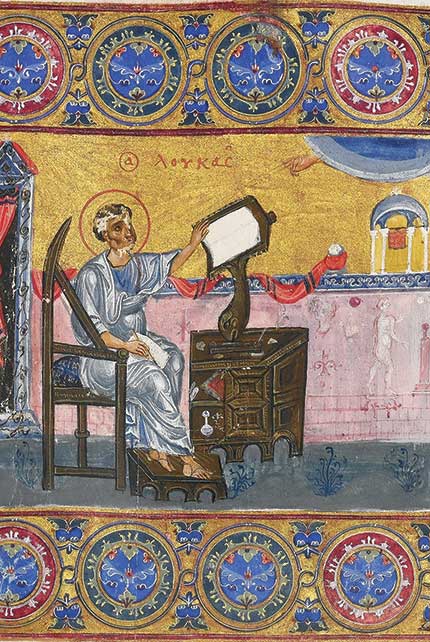

Ordinary Time, especially Sundays after Pentecost

[ABOVE: Jaharis Byzantine Lectionary, 12th century. Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment; leather binding—Metropolitan Museum of Art / [CC0] Wikimedia]

What about the times in the church year when no special feast cycle is happening?

Where did it come from?

The term “Ordinary Time” is actually quite recent—it resulted from Vatican II’s liturgical changes as a new way to describe the Sundays after Epiphany (i.e., between Epiphany and Ash Wednesday) and the Sundays after Pentecost (i.e., between Pentecost and the First Sunday of Advent). The Latin term used by the Catholic church is tempus per annum, which literally means “time of the year.” This is an exclusively Western term—in the Eastern church, Sundays during this whole time (including, usually, the ones between Epiphany/Theophany and Lent) are simply called “Sundays after Pentecost.”

Despite the newness of the term, the occurrence of these two periods is quite ancient; the marking of these Sundays dates all the way back to when the basic shape of the church year came to be, which mostly happened by the fourth century.

The term “ordinary” officially refers to the ordinal numbers used in counting Sundays (First, Second, Third, etc.). The term perpetually gets understood, or misunderstood, as being ordinary in the sense that nothing special is happening. It is true that some originators of the term wanted people to focus simply on every Sunday’s celebration of the Resurrection without relating it to a particular cycle of feasts.

How is the date determined?

Ordinary Time varies in length because it depends on the dates of some of the church year’s movable feasts. The date of Easter controls the length of the period between Epiphany and the beginning of Lent. (We’ve already discussed some emphases during this time when talking about Epiphany on pp. 16–19.) The length of the period between Pentecost and the First Sunday of Advent is controlled both by the date of Easter (which determines the date of Pentecost) and the Sunday on which Advent starts, which may be either the last Sunday of November or the first Sunday of December (see pp. 8–9).

Since Vatican II the Roman Catholic church considers both “pieces” of Ordinary Time to be one long season, skipping over the Lent-Easter-Pentecost cycle in the middle. The Sundays are numbered consecutively and the lectionary readings are unified (more on this below). This season in total is normally 33 weeks long.

Among Protestants who follow the Revised Common Lectionary, the Sundays after Epiphany, while they may be referred to as Ordinary Time, have much more of an Epiphany “flavor” and are usually called Sundays after Epiphany. Many Protestants will think mostly of the Sundays after Pentecost as truly Ordinary Time. As many as 26 weeks of this Ordinary Time occur during the calendar year.

For about 60 years—from the late 1930s to the early 1990s—United Methodists and some Presbyterians adopted the name “Kingdomtide” for the second half of the time between Pentecost and Advent to emphasize Christian social concern. They began Kingdomtide sometime in August. Shortly after this observance had essentially died out among its originators, Anglicans in Britain began observing a “Kingdom Season” between All Saints’ Day and the First Sunday of Advent. A number of Roman Catholics and liturgical Protestants observe the month of September during Ordinary Time as the “Season of Creation,” with a focus on caring for God’s creation.

The Eastern church, as already mentioned, generally thinks of the time between Pentecost and the Nativity Fast and the time between Theophany and Clean Monday simply as Sundays after Pentecost. Thirty-seven weeks normally make up this period for the Eastern church.

Theological themes

In the West, while many churches don’t currently observe an explicitly named “Kingdom Season” during this time, the general focus of the entire season could be said to be the Kingdom of God—spreading through the world, shown in deeds of mercy and care for each other and for creation, and coming into its fullness at the end of time. Themes vary by Sunday, but since lectionary Scripture readings often flow continuously through a book or books of the Bible, preachers and worship leaders can focus on different themes and stories from the Bible over multiple Sundays.

The East takes a similar approach in terms of readings; they vary according to the Sunday but also proceed in a broadly continuous fashion. Since these Gospel readings often tell the story of Jesus’s miracles and parables, worship implicitly focuses on the new life of the Kingdom, but it is not called out in the way that became common in the twentieth-century West.

Colors

In the West green is used; in the East, gold. Denominations that observed Kingdomtide when it was in vogue would sometimes use red from Pentecost until Kingdomtide began and then switch to green. Churches that observe Kingdom Season now often do the opposite—green for most of the season and red in November. The Season of Creation has no special colors.

Customs

No particular customs are associated with Ordinary Time other than the regular Sunday celebration of the Eucharist and the honoring of the various saints’ days that might fall within it (see pp. 46–49). The most noticeable thing about this season is probably the opportunity to move continuously through the Bible at length from Sunday to Sunday. All of the three major branches of Christianity do this, but they each do it differently. (Some of this gets pretty technical, but if you are ever worshiping in a church that uses this system, it may be helpful to know where the readings come from.)

To understand how this system works, it’s helpful to know the liturgical term “propers.” Propers are service elements that change from week to week in denominations that use a set formal liturgy. The propers are called this because they are “proper” for a certain day, and they normally include all the Scripture readings and some prayers. It also helps to know that both Protestants and Roman Catholics use a three-year cycle of propers (calling them Years A, B, and C); the Orthodox use a one-year cycle and repeat the same readings every year.

As noted, Ordinary Time begins the Monday after the First Sunday after Epiphany for Roman Catholics. Sundays in Ordinary Time begin with the Second Sunday after Epiphany, skip the Lent-Easter cycle, resume after Pentecost, and are numbered 2–33. The Sundays are often referred to by the number of their propers, at least when planning worship (so someone planning worship for the Second Sunday after Epiphany would be doing so for Proper 2).

In each year a different Gospel is read through semi-continuously during this time: in Year A, Matthew; in Year B, Mark (and, because Mark is so short, parts of John); in Year C, Luke. The Epistle lessons are also read semi-continuously; over the three years, believers will hear most of Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Philemon, Hebrews, James, and a little of Revelation. Old Testament readings for each week are chosen to amplify the themes of the Gospel readings.

Among Protestants who use the Revised Common Lectionary, while the Sundays after Epiphany are “technically” Ordinary Time, they are not part of the numbering system. Ordinary Time as most Protestants conceive of it begins on the Monday after Pentecost, and the Sundays in Ordinary Time begin with Trinity Sunday, which is also the Second Sunday after Pentecost. The rest of the Sundays are numbered from 3 through 29. The same system is used for the Gospel and Epistle readings as in Roman Catholicism, but Protestants can choose between using the Catholic system for the Old Testament readings or reading semi-continuously through a part of the Old Testament—Genesis and Exodus in Year A, the historical books in Year B, and the prophets in Year C.

In years when Easter is later and Ordinary Time is shorter, both Protestants and Catholics skip the readings for earlier propers, so that the concluding sets of readings—which in all three years speak about Christ’s Second Coming and prepare believers for Advent—are always heard.

Orthodox numbering of the season after Pentecost starts on the Sunday after Pentecost (calling it the First Sunday after Pentecost), skips the Nativity-Theophany cycle, and resumes after Theophany. (For more on special observances on the last four Sundays before Great Lent, see pp. 23–25.) The Sundays are numbered from 1 through 37, and the Epistle and Gospel readings move semi-continuously through multiple books of the Bible in a single year. The Old Testament is not normally read at an Orthodox Eucharistic service, but it is normally read at Vespers. CH

Some things to do at home

• Ordinary Time is a great time to start a Bible study—especially of the Scriptures used in the lectionary.

• Think about ways you can spread the message of God’s Kingdom.

• Look for ways in which you can help care for creation.

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #156+ in 2025]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is Senior Editor of CH magazineNext articles

Celebrating the saints: the sanctoral cycle

Saints are normally honored on the anniversary of their death

Jennifer Woodruff TaitRecommended resources: Fasts and Feasts

Learn more about the history of the Christian year, and get ideas for incorporating celebrations into your own life.

The editorsQuestions for reflection: Fasts and feasts of the church

Reflect on themes of sacred time.

The editors