Freedom in Pennsylvania

WHEN SCHWENCKFELD DIED 1561, a number of small groups of his followers were located in south Germany around Strasbourg, in the Ulm-Augsburg area, and in Silesia.

By the close of the Thirty Years War in 1648, however, only the Silesian remnants remained. At the opening of the eighteenth century there were less than 1,500 persons left in Lower Silesia who adhered to the tradition.

In 1719 the Emperor of Austria established a Jesuit mission to bring these remaining Schwenckfelders into the Catholic Church. The mission was directed by two priests, Johann Milan and Carolus Regent, who immediately began to impose fines and imprisonments.

A deputation sent to Vienna to plea for their case could achieve nothing, so in 1726 over 500 persons fled Silesia, leaving their property and all the possesions they could not carry with them. They filled mangers and feed troughs before they left; it might be days before their absence was realized and the animals would be fed again.

Help from Zinzendorf

Some found refuge in the Saxon city of Görlitz; others went to the estate in Saxony of Count Nikolaus Ludwig van Zinzendorf who had already offered sanctuary to the Moravians. [The story of Count Zinzendorf and the Moravians appeared in the first issue of CHRISTIAN HISTORY.] Here the majority remained until 1734, when political pressures were brought to bear on the Count to withdraw his support.

The largest contingent of the Schwenckfelders (some 180 persons) left Saxony in April 1734, travelling down the Elbe and across to Holland. There they boarded a British vessel, the St. Andrew, and sailed for Pennsylvania where several of their co-believers had fled a few years earlier.

They arrived in Philadephia Harbor on September 22 and two days later, on 24 September 1734, held a thanksgiving service which they have celebrated annually ever since.

Although their religious thought owed its major thrust to the tradition of Schwenckfeld, there were wide differences among them in its interpretation. Some drew closer to the Moravian tradition, others to radical Pietist groups such as the Church of the Brethren, and yet others were attracted by the theosophical speculation of the influential German mystical writer Jacob Boehme (1575–1624).

Home in Pennsylvania

Unable to find a single section of land on which to settle, they found themselves spread throughout present-day Montgomery County, the two major groups establishing themselves in what would be called the Lower District, in the vicinity of Lansdale, and in the Upper District near Pennsburg.

Here they soon established prosperous religious and social communities. Later in the century, they built meeting houses and formed schools for educating their own children and those of others. Contact with their fellow-believers in Silesia was maintained for a time, but slowly ceased. In part this was caused by the decline of Schwenckfeldianism in Europe where the last Schwenckfelder died in 1826.

In eighteenth-century America the Schwenckfelder intellectual tradition remained strong. They continued to copy the books of their tradition, and under the leadership of George Weiss, Balthasar Hoffmann, and Christopher Schultz, they renewed their religious life. In 1762 they published a large compilation of hymns for their use, a great many of which were by Schwenckfelders.

All their leaders continued to write religious treatises and biblical exegesis. At the end of the eighteenth century they published the sermons of Erasmus Weichenhan, which they read weekly in their meetings. Early in the next century they undertook a program to publish the major works of their founder.

Preserving a Tradition

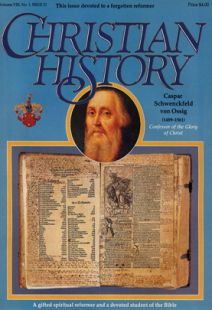

In 1884, the 150th anniversary of the Schwenckfelders’ safe arrival in America, Chester David Hartranft, a professor at Hartford Theological Seminary in Connecticut, and a descendant of the original 1734 emigrants, suggested that they undertake a critical edition of Schwenckfeld’s works. Along with this project they began a campaign to gather the books and manuscripts scattered among them and to collect major works related to the tradition in Europe.

The edition of Schwenckfeld’s works was entitled the Corpus Schwenckfeldianorum and it was brought to a completion with the publication of its 19th volume in 1961, the 400th anniversary of Schwenckfeld’s death.

The leading academic figure in this project was Selina Gerhard Schultz, who began with the project in the early twentieth century as a secretary. She eventually became the editor-in-chief, and saw it through to its end. For her scholarly dedication and achievement she was honoured by the University of Tübingen with a doctorate.

Throughout the final 30 years of the Corpus project she and others were encouraged with the personal and financial support of Wayne C. Meschter, who had also taken a special interest in the library. In the early 1950s, when the library’s holdings outgrew the space available in a building provided through the Carnegie Foundation in 1913, Meschter directed the construction of a new library building to preserve the collection. The present Library collection is comprised of some 25,000 rare books and manuscripts, the earliest dating from the fifteenth century.

The present Schwenckfelder Church has five congregations in southeastern Pennsylvania and some 2,500 members. CH

By the Editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #21 in 1989]

Next articles

Christian History Chronology: The Hard Journey to America

One Schwenckfelder left us an account, in diary form, of the crossing to Pennsylvania.

the EditorsFrom the Archives: Christian Self-Surrender

If we seek God only for the sake of His pure goodness, and not desire more than His pleasure, reward will follow without our seeking.

Caspar SchwenckfeldFrom the Archives: Christian Patience and Humility

A Letter to a Mother and Her Children.

Caspar Schwenckfeld