From Cana to Jell-O

We’ve all been to a church dinner: the long table covered in casseroles and crockpots, too many desserts, not enough vegetables, three kinds of macaroni. Parents are trying to corral excited children, and everyone’s scanning the room for a seat with people they like or at least know.

Christians didn’t invent the practice of social meals. Pagan Greeks and Romans participated at symposia, weddings, and funerals; Jewish weddings and Passover observances brought family, friends, and neighbors together to share a meal.

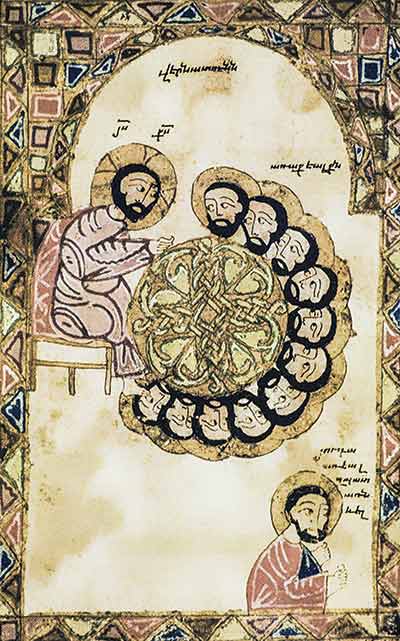

Jesus instituted not only the Eucharist, but Christian fellowship meals. His public ministry began when he changed water into wine at a wedding feast in Cana (John 2:1–12) and expanded when he miraculously fed multitudes. It’s no surprise that he dined with his disciples, but he also ate with “tax collectors and sinners” and Pharisees. After his Resurrection, he even revealed himself to fellow travelers during a meal at Emmaus:

When he was at the table with them, he took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them. Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him; and he vanished from their sight. (Luke 24:30–31)

no couches in church

The Bible describes early church social dining experiences after the Resurrection, soon called agape feasts or love feasts (Acts 2:42; 1 Cor. 11:17–34; Jude 12). These events involved a regular meal, a message of exhortation, and the Eucharist. Pastoral letters, apologetic works, and the church manual called the Didache all refer to these as a kind of church supper and Lord’s Supper all rolled into one.

Congregations soon began to separate the two meals, opting for the Eucharist in the morning and a love feast in the evening. By the third century, the Roman Empire had forbidden meals shared among secret societies—bad news for the love feast. The regional Council of Laodicea in 363–364 announced: “It is not permitted to hold love feasts, as they are called, in the Lord’s Houses, or churches, nor to eat and to spread couches in the house of God.” The Trullan Council reaffirmed this in 692.

But food and fellowship remained fixtures of community life. Medieval western Europe observed about 50 feast days per year—essentially one per week. They served as respites from labor and commemorated saints from the Bible or from church history and legend.

Specific foods became associated with certain saints and days: eel for Christmas Eve in Italy, mince pie for Christmas in England, king’s bread for the Epiphany in Spain, soup with greens for Maundy Thursday in France, leeks in Wales for St. David’s Day, ginger scones for St. Ninian’s Day in Scotland, and pancakes for Shrove Tuesday everywhere. The Eastern Orthodox tradition had its own set of holy foods and days, such as vasilopita (bread) baked for St. Basil’s Day.

In the late 1700s, Carmelite missionary Paolino da San Bartolomeo encountered Indian Christians who traced their spiritual lineage to the apostle Thomas and had never stopped practicing love feasts in their worship, eating appam (pancakes of rice and coconut milk). But for Westerners, the Protestant Reformation’s impulse to restore primitive Christianity eventually led to bringing the love feast back as a spiritual and social practice.

The Schwarzenau Brethren, also called German Baptists or Dunkers, reclaimed love feasts for evening worship in the early 1700s. To this day their successors, the Church of the Brethren, hold love feasts on Maundy Thursday, including ceremonial foot washing and Eucharist (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover). The Moravians (who called themselves Unitas Fratrum or Unity of the Brethren) also re-instituted the love feast in 1727.

Methodists were the most significant contributors to the spread of love feasts in the United States. John Wesley first encountered Moravians traveling to Georgia by ship in 1736, singing and praying during a storm while he cowered in fear of shipwreck. Moravian piety impressed Wesley, and after he returned to England, he had his famed heart-transforming experience in 1738 at a Moravian meeting. Moravians inspired Methodist use of the love feast to strengthen community among members.

Love feasts served practical purposes for Methodists too. Local Methodist societies outnumbered ordained clergy. They relied on local lay preachers who could exhort from the Bible and lead a society. They practiced love feasts to build social bonds and fulfill what they saw as a biblical imperative to break bread together.

At these lay-led meetings, Methodists shouted, prayed, and sang hymns like this one recorded by Ebenezer Hills: “We come from far to taste thy love / And brethren here to meet. . . . / A feast of love we then shall keep / Of perfect love professed, / At God’s right hand then take a seat / And reign among the blest.” By the middle of the nineteenth century, the church had enough ordained Methodist clergy to go around, and love feasts faded as impractical—and too noisy.

Love feasts weren’t bound to orthodoxy; early Latter-day Saints embraced the concept. The “feasts of fat things” (Isa. 25:6) were communal meals to which impoverished members of the church were invited and well fed; Mormon hymnwriter William Phelps wrote: “There’s a feast of fat things for the righteous preparing / That the good of this world all the saints may be sharing. . . . Come to the supper of the great Bridegroom.”

At the Kirtland Temple in Ohio, the first LDS temple, Mormons also engaged in a “solemn assembly” with a shared meal, Bible lessons, exhortation, prayer, and personal testimonies. Finally, “blessing feasts” involved male church leaders gathered for dinner and to receive blessings as patriarchs.

Choking on a peach pit

The first half of the nineteenth century was also the heyday of revival camp meetings. Attendees cooked for themselves, and campers shared their surplus in community meals. The New York Times, in a satirical article reporting on a Methodist camp meeting in Sing Sing (now Ossining), New York, in 1865, commented, “The food obtained on the ground is generally of a very good quality.” At that meeting preacher John Inskip choked on a peach pit, the Times reported; after he finally swallowed it, “a hymn of praise was sung, and an old lady some distance away cried out at the top of her voice: ‘Bless God, I know it’s down, for they are singing!’”

Some decades later when camp meetings had begun to evolve into institutions with fixed locations and permanent facilities, Ellen White (see “The sacred duty,” p. 40) described what food would be best for a good camp meeting:

If [attendees] make no cake or pies, but cook simple graham bread, and depend on fruit, canned or dried, they need not get sick in preparing for the meeting, and they need not be sick while at the meeting. None should go through the entire meeting without some warm food. There are always cookstoves upon the ground, where this may be obtained.

In the twentieth century, urban church facilities began to include large kitchens and dining halls to serve food to the destitute, essential during the Great Depression. Smaller churches hosting communal meals required parishioners to bring food items to “carry-ins” or “potlucks” (see “Did You Know?,” inside front cover).

Following World War II, Americans moved out of compact urban neighborhoods into sprawling suburbs. Feelings of isolation prompted the creation of community centers, reception halls, and fellowship halls . . . and more potlucks. Innovative foodwares allowed food to be stored and transported: Pyrex glassware (1908), Tupperware (1948), and Corningware (1958). Electricity-powered refrigeration, spurred on by the public works projects of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, also aided the potluck.

you can put it in jell-o

And then there was Jell-O. Invented in 1897, this gelatin became popular due to an aggressive marketing campaign that distributed cookbooks with recipes for congealed salads. By the 1930s people were suspending fruit, vegetables, and even pasta in molded Jell-O; two real potluck recipes from the 1950s call for tuna with pimiento-stuffed olives in tomato Jell-O and lemon Jell-O with cabbage, radishes, eggs, and chives.

Roman Catholics and Orthodox continue to put their own special twists on communal meals. The traditional Roman Catholic abstention from meat on Fridays means church-sponsored fish dinners; in many cities, parishes or caterers distribute fish fry schedules for each Friday of Lent. Catholic “Beef and Beer” fund-raisers seem to have taken the name from Catholic convert G. K. Chesterton (1874–1936), who claimed to defend “the institutions of Beef and Beer” against the “hygienic severity of vegetarianism and total abstinence” of his friend George Bernard Shaw (see “What would Jesus buy?,” pp. 36–39).

Orthodox Christians observe a stringent Great Lent fast, much longer than that of Western churches, by abstaining from all meat, fish, dairy, oils, and wine. They conclude Holy Week with an Easter vigil that begins at midnight and goes on for hours, often ending after sunrise. With the liturgical refrain “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death; and upon those in the tombs bestowing life!” still echoing in their ears, they celebrate breaking the fast with a large potluck of no-longer-prohibited foods, among them lamb soup, bread, cheese, and eggs.

Another form of communal meal-sharing exists in the Amish tradition of barn raisings, all-day construction projects that require multiple community meals. And, in the twenty-first century, love feasts have found new life in emergent communities and house churches attempting to connect ancient Christian practice and modern-day mission. Some theologians and pastors use the love feast to advocate for inclusion of people whom the church has historically excluded.

After 2,000 years Christians are still eating fellowship meals. A recent issue of COV, the magazine of the Evangelical Covenant Church, asked, “Whatever happened to the church potluck?” Not to worry, commentators said; potlucks are alive and well in their churches. One pastor from Alaska shared a typical Alaskan potluck menu: “Moose, goose, muktuk, seal, seal oil, fish prepared in different ways . . . [and] akutaq—a berry, sugar, and Crisco whipped dessert.” Another added, “The shared meal is where Jesus makes himself known, and it is where the body finds communal expression. . . . I hold to a pretty high theology of believers dining together.” CH

By Barton E. Price

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #125 in 2018]

Barton E. Price is director of the Centers for Academic Success and Achievement at Indiana University–Purdue University Ft. Wayne and teaches history, music, and religious studies.Next articles

Food in Christian history: Recommended resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you understand the story of food and faith.

the editorsBaptists, Did you know?

Baptists “churching themselves,” founding schools, joining the army, and climbing trees

The editor and various contributors.