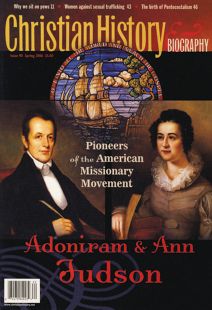

From Sea to Shining Sea

And then he always loved the sea so dearly!“ said Emily Judson of her husband's dying days aboard the French bark, Aristide Marie, in 1850. Although no prayerful tribute or elaborate headstone marked Adoniram Judson's watery grave, Emily thought it appropriate that he was buried at sea. ”Neither could he have a more fitting monument than the blue waves which visit every coast; for his warm sympathies went forth to the ends of the earth."

Born in Massachusetts, the 18th-century heart of maritime America, Adoniram grew up near Salem just as the port entered the profitable East Indies trade. By 1805, American ships had imported more than ten million pounds of tea from China and eight million pounds of pepper from the East Indies, not to mention innumerable trade goods to decorate fashionable New England homes.

As the exotic products of southern Asia spread through the region, so did stories of strange cultures and people who did not know the Christian God. Sailors brought back descriptions and drawings of “Hindoos” who “made pilgrimage for to bathe in the Great River Ganges which they hold most Sacred.” A whole new world opened to the young men and women who matured during America's first global awakening. Thus it was no coincidence that the dying Adoniram expressed his love for the sea, for the ocean had literally brought him his calling.

The growth in international seaborne commerce made worldwide missions possible, but also difficult. The voyages of the 19th-century missionaries illustrates this tension. The same ocean that divided missionaries, often permanently, from their native land offered these modern Argonauts the opportunity to carry the gospel of Jesus Christ to previously unknown worlds.

One-way ticket

Time and space formed the first obstacles for the early American missionaries, who faced a four- to six–month-long voyage to a destination nearly 10,000 miles away. The missionaries felt keenly the separation from family and friends. Even the beauty of a gentle sea on a moonlit night could not ease Ann Judson's melancholy. “My native land, my home, my friends, and all my forsaken enjoyments, rushed into my mind; my tears flowed profusely, and I could not be comforted.” While second voyages were not out of the question, missionaries did not anticipate them. As Harriet, the wife of Samuel Newell, later wrote her sister, “I used to think, when on the water, that I never should return to America again, let my circumstances in Asia be as bad as they could be.” The distance and time involved in an ocean voyage before the invention of steamships meant that most missionaries purchased only one passage.

Since the missionaries fully expected that they would never return home, written correspondence carried by an amenable ship's captain furnished their only earthly link with those they missed. No wonder they were inveterate letter writers, seizing every opportunity to write home once they arrived in the mission field. Harriet Newell frequently confided in her journal (addressed to her mother), “You know not how much I think of you all, how ardently I desire to hear from you, and see you.” Specific replies to letters might not come for at least a year.

Life aboard the ship itself involved a major lifestyle change. Maximizing cargo space made for close and cramped living quarters. Sleeping compartments were not normally more than four feet wide and five feet long. Because the missionaries were middle-class professionals, they shared the cabin space with the ship's officers. Thus they were usually spared confinement below decks, where poorer passengers resided among the ship's cargo. Even these relatively more favorable conditions gave rise to complaints. Harriet lamented, “The vessel is very damp, and the cabin collects some dirt, which renders it necessary that I should frequently change my clothes, in order to appear decent. I think I shall have clothes enough for the voyage, by taking a little care.”

Caution: dangerous mission ahead

The discomforts and dangers at sea made the prospects of death very real. Constant or recurring motion sickness, even when the ship was not pitching in a violent storm, left travelers severely weakened and vulnerable to more serious illnesses. The voyage preyed on the weak. Both Ann Judson and Harriet Newell gave birth at sea. Neither child survived. The ship could be both lifeline and coffin.

One missionary confided in her journal her “distressing apprehensions of death. Felt unwilling to die on the sea, not so much on account of my state after death, as the dreadfulness of perishing amid the waves.” This trepidation colored the missionaries' views of the labors ahead of them, which they expected to be “a life of privations and hardships.” The voyage gave them the time to ponder the formidable task before them and to steel their resolves for the prospects of an imminent death.

Harriet described to her mother conversations that took place during the sea voyage: “I feel a sweet satisfaction in reflecting upon the undertaking in which I have engaged. It is not to acquire the riches and honours of this fading world; but to assist one of Christ's dear ministers in carrying the glad tidings of salvation to the perishing heathen in Asia.”

Theology and jump rope

Despite the numerous challenges, life on ship was not always painful. The ocean that separated the missionaries from their friends and families also offered them the opportunity to become better acquainted with their calling—and with each other. The first Atlantic crossing in 1812 formed the honeymoon period of the Judsons' and the Newells' marital and missionary lives. In addition to adapting to the difficulties of an extended sea voyage, the newlyweds entered into married life temporarily free of toilsome responsibilities. They used the time to get to know each other.

Passengers passed the time conversing with each other over meals, during games, and as they reclined in their sleeping berths at night. Sabbath days aboard ship became particularly enjoyable when their private dialogues manifested themselves in public praise. Harriet hoped her mother had as profitable Sundays as those she experienced aboard the Caravan. “I have spent a part of this holy day on deck, reading, singing, conversing, &c.” Her shipboard life assumed a simple but happy rhythm. Ann Judson even organized jumping rope on deck as a form of exercise and entertainment. Companionship was essential to the happiness of a voyage.

Reading also assumed a central place on board ships. As Harriet noted, few other entertainment options existed. “I shall devote much of my time to reading while on the water. There is but little variety in a sea life.” In Ann's opinion, this lack of variety produced an unprecedented opportunity for studying the Scriptures. “I do not recollect any period of my life, in which I have, for so long a time, had such constant peace of mind. . . . Have gained much clearer views of the Christian religion, its blessed tendency, its unrivalled excellence.” During the course of the voyage, Ann read “the New Testament, once through in course, two volumes of Scott's Commentary on the Old, Paley, Trumbull, and Dick, on the Inspiration of the Scriptures, together with Faber and Smith on the Prophecies.” Through study, shipboard time was a chance to prepare for the future mission.

The most famous occurrence aboard the Caravan—Adoniram Judson's change of views regarding infant baptism—highlights the importance of shipboard reading. For one of Adoniram's early biographers, “The only event on the passage which has become specially worthy of note is the fact that Mr. Judson availed himself of this period of leisure to investigate anew the scriptural authority for infant baptism.” The voyage gave time for lingering doubts about infant baptism to fester into open disbelief on the matter.

In the later 19th century, the British man of letters John Ruskin noted the international intimacy made possible by oceanic commerce: “The nails that fasten together the planks of the boat's bow are the rivets of the fellowship of the world.” This sentiment proved especially true of America's first missionaries as they spread across the rim of the Pacific and Indian oceans. Ships initiated missionaries into their foreign callings, created thin lifelines with their families and supporters, and covered their lives with the watery veil of death.

Harriet, the first of the earliest American missionaries to die, left perhaps the most fitting epitaph of their life at sea and its lasting effects: “My attachment to the world has greatly lessened, since I left my country, and with it all the honours, pleasures, and riches of life. Yes, mamma, I feel this morning like a pilgrim and a traveler in a dry and thirsty land, where no water is. Heaven is my home; there, I trust, my weary soul will sweetly rest, after a tempestuous voyage across the ocean of life.”

By Stephen R. Berry

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #90 in 2006]

Stephen R. Berry is a visiting instructor at Duke Divinity School in Durham, North Carolina.